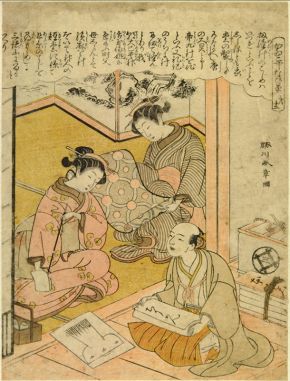

Woodblock print, 'The Cultivation of Silkworms', Katsukawa Shunsho (1726-1792), Japan, 1767-1768. Museum no. E.1360-1922, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Woodblock print, 'The Cultivation of Silkworms', Katsukawa Shunsho (1726-1792), Japan, 1767-1768. Museum no. E.1360-1922, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Kimono are made from single bolts of cloth, about 36cm wide and 11 metres long, which are cut into seven straight pieces. Two panels - each extending up the front, over the shoulder and down the back - create the body, two the sleeves, two more the overlaps, and a narrower panel the neckband.

This simplicity of construction meant that kimono could be sewn in the home. In the Edo period many households, particularly in rural areas, also had their own loom, and a woman's sewing and weaving abilities were considered very important. The creation of sumptuous silk kimono, however, required the skills of specialist artisans, the majority of whom were men. Fashion was big business and supported an extensive network that included spinners, weavers, dyers, embroiderers, specialist thread suppliers, stencil makers and designers. At the heart of the industry were the drapery stores, the most famous of which was the Echigo-ya in Edo founded in 1673 by Mitsui Takatoshi. Merchants such as Mitsui not only sold kimono fabric, but orchestrated the activities of the various specialist workshops involved in the creation of individually commissioned garments.

When choosing a kimono design, customers, and also the makers and sellers of kimono, could turn to pattern books (hinagata-bon) for assistance. These contained illustrations of the back of kimono with accompanying notes on colour and decoration. Books showing kimono being worn were also published, not so much to provide practical help but for the pleasure of thumbing through them, rather like today's fashion magazines.

The western textile technology introduced to Japan in the Meiji period speeded up production and lowered costs. At the turn of the 20th century many drapery stores transformed themselves into modern departments stores. Echigo-ya, for example, became Mitsukoshi, which remains one of Japan's leading retailers. Since the Second World War the wearing of traditional garments has dramatically declined, but today such stores still have kimono departments. Nowadays most production is automated, but some makers continue to utilise traditional skills in the creation of contemporary kimono.

Dyeing techniques

Kimono, Japan, 1800-1850, silk crepe (chirimen) with tie-dyeing (shibori), paste-resist dyeing (yuzen) and embroidery. Museum no. T.109-1954, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Most of the dyes used to colour Japanese textiles, and many of the techniques used to apply them, have a history that dates back to the 8th century. However, it was not until the Edo period that the sophisticated dyed designs for which Japan is famous fully developed. Dyeing is a very specialised skill and the top dye houses carefully guarded their secrets. Kyoto was the dye centre of Japan, but no village was without its own dye house.

In Japan a variety of resist-dyeing methods are used. Shibori, or tie-dyeing, involves the binding, stitching, folding or clamping of the cloth prior to immersion in the dye, the colour thus not penetrating the protected areas. In one of the most distinctive Japanese techniques, kanoko shibori, closely placed small circles in diagonal rows are bound tightly with thread before dyeing. In stencil dyeing, or katazome, rice paste is applied through a stencil onto the cloth. The stencil is then removed and placed on the next section of fabric and the process repeated. When the cloth is dyed the colour does not penetrate the areas covered with the paste, which is then washed away once the dye is dry.

Rice paste is also utilised in yūzen, in which a cloth tube fitted with a metal tip is used to apply a thin ribbon of paste to the outline of a drawing on the fabric. Dyes are then brushed within the paste boundaries. This technique, named after Miyazaki Yūzen, the artist monk credited with inventing it, developed in the 18th century. It allowed for extremely detailed patterning and gave kimono designers almost unlimited freedom of expression.

In the second half of the 19th century the dyer's palette was expanded by the introduction of chemical dyes and in the late 1870s a method was devised of directly applying pre-coloured paste through stencils. In the 20th century traditional methods of dyeing survived alongside increasingly automated methods and today are preserved by a number of leading kimono makers who use them to create highly contemporary designs.

Embroidery

Kimono, Japan, 1820-60, satin silk known as shu, embroidered in silk & metallic thread with decoration of ducks on rippling water amongst irises and pinks. Museum no. T.79-1927, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Like other patterning methods, Japanese embroidery has a long history and reached its peak of technical sophistication in the Edo period. Exploiting the freedom the technique allows, and utilising a myriad of colours and an extensive range of stitches, embroiderers have produced some of the most striking of all Japanese textiles. Embroidery was often used in conjunction with dyeing, the combination of techniques giving designs a variety of texture and visual depth. When embroidery was the sole decorative method, a satin fabric was commonly used, giving an extremely lustrous effect.

Japanese embroiderers employ a number of different stitches. A flat stitch (hira-nui), equivalent to satin stitch in the West, is used to create pattern elements such as flowers and leaves. These stitches use floss (untwisted) silk, which gives the embroidery a very rich sheen. A tiny gap, equivalent to the point of the needle, is used to delineate elements such as the separate petals of flowers or the central veins of leaves. Larger areas are defined with long and short stitches (sashi-nui), also in floss silk. Twisted threads, generally in pairs, are also used. In katayori, one thread is highly twisted and then twisted, more lightly and in the opposite direction, with another thread, giving a nubbled appearance. Another type of texture is created with a knot stitch (sagura-nui). Metallic thread is also used to dazzling effect in Japanese embroidery. This is made from a silk core wrapped in paper and then with gold or silver leaf. The resulting thread is too thick to pass through fine silk without damaging it, so is couched (attached with small stitches) on to the fabric.

In Japan a number of other decorative techniques involve the use of a needle and thread. In Tsugaru, the northernmost part of Japan's main island Honshū, kimono are embellished using a method called kogin, in which white stitches are embroidered over and under an odd number of warps on the woven ground fabric to create a diamond pattern.

Weaving techniques

Kimono, 'Blue Mountains and Green Rivers', Tsuchiya Yoshinori, Japan, 2004. Museum no. FE.144-2006, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The simplest way of weaving fabric is to pass the weft (horizontal) thread over and under each successive warp (vertical) thread. This is known as plain weave (hira-ori) and in Japan is the principal method used in the creation of cotton, hemp, ramie and certain kinds of silk fabrics.

Stripes and checks are produced by using different coloured threads, while more elaborate patterns can be created by weaving with selectively pre-dyed threads, as in the technique known as kasuri. Silk crepe (chirimen) is also a plain weave, but has a crimped appearnance that is produced by over-twisting the weft threads.

Passing the weft over or under two or more warps creates what is known as a float. In satin (shu) long floats are created by passing the weft over or under four or more warps which gives the fabric a lustrous appearance.

In float weaves the surface of the fabric can show either predominantly warps or predominantly wefts depending on the weaving sequence. By using different combinations of floats, patterns can be created in the cloth as in rinzu, a monochrome figured satin similar to damask. Like chirimen, rinzu was introduced to Japan from China in the 16th century.The patterns that adorn kimono are very significant, for it is through choice of colour and, most importantly, decorative motifs that the wearer's gender, age, status, wealth, and taste are articulated.

At the beginning of the Edo period there were no substantial differences between the kimono worn by men and women, but distinctions became more pronounced in the course of the 17th century. The patterns on women's kimono became larger and bolder. Younger women's kimono were particularly lavishly decorated and brightly coloured, while more subtle patterning and subdued colours were considered appropriate for an older woman. The length of the sleeve also varied. Young women wore their sleeves long, a fashion that became particularly pronounced from the mid-Edo period onwards, but shortened them once they married. Men wore even shorter sleeves, while the patterns and colouring on their garments was generally quite restrained.

At the beginning of the 17th century the surface of the kimono was divided into irregular pattern areas. Over time such compartmentalisation gave way to an approach which considered the garment as a whole, and in which technique and motif, pattern and ground were fully integrated. The disposition of the pattern on the surface of the garment also changed over time. Nature, particularly seasonal references, provided a major source of designs, together with allusions to classical literature. The increased market for luxury kimono led to a broadening of the visual repertoire to include aspects of popular culture and visual puns. The range of patterns widened yet further during the late 19th century when western motifs were introduced.

With the taste for dynamic, unified motifs, the clean, straight lines of the T-shaped garment served as a blank canvas, or scroll, for the kimono designer. It is important to remember, however, that kimono are 3-dimensional objects that move with the wearer. The simplicity of structure also belies the fact that donning a kimono, often in a number of layers, with an obi and other accessories, creates a rich and often visually complex effect.

Symbolism

Kimono, Japan, early 19th - mid 20th century. Museum no. T.18-1963, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The images used on kimono often have complex levels of meaning, and many have specific auspicious significance which derives from religious or popular beliefs. The crane for example, is one of the most popular birds depicted on kimono. Believed to live for a thousand years and to inhabit the land of the immortals it is a symbol of longevity and good fortune.

The use of specific motifs can allude to the virtues or attributes of the wearer (or those they might aspire to), reflect particular emotions, or relate to the season or occasion. Such symbolism was used especially on kimono worn for celebratory events such as weddings and festivals, when it served to bestow good fortune on the wearer, wrapping them in divine benevolence and protection. This use of auspicious motifs in dress reveals the Japanese belief in the literal, as well as the figurative, power of images.

Colours too have strong metaphorical and cultural connotations. Dyes are seen to embody the spirit of the plants from which they are extracted. Any medicinal property is also believed to be transferred to the coloured cloth. Blue, for example, derives from indigo (ai), which is used to treat bites and stings, so wearing blue fabric serves as a repellent to snakes and insects. Colours were given a cosmological dimension with the introduction to Japan in the 6th century of the Chinese concept of the five elements. Fire, water, earth, wood and metal are associated with particular directions, seasons, virtues and colours. Thus black corresponds to water, north, winter and wisdom. Colours also have strong poetic significance. Purple, for example, is a metaphor for undying love, the imagery deriving from the fact that gromwell (murasaki), the plant used to create the dye, has very long roots. Perhaps the most popular colour for kimono is red, derived from safflower (benibana). Red connotes youthful glamour and allure, and is thus suitable for the garments of young women. It is also a symbol of passionate but, as beni-red easily fades, transient love.

Natural motifs

The natural world provides the richest source for kimono motifs. Numerous flowers such as peonies, wisteria, bush clover and hollyhocks appear on garments. Many of them, for example cherry blossom, chrysanthemums and maple leaves, have a seasonal significance.

Pine, bamboo and plum are known collectively as the Three Friends of Winter (shōchikubai), and are symbols of longevity, perseverance and renewal. The pine tree is an evergreen and lives for many years, bamboo bends in the wind but never breaks, and the plum is the first tree to blossom each year. The plum is particularly favoured for winter kimono, for its use suggests that spring cannot be far away.

Birds, animals, butterflies and dragonflies also appear on kimono, along with other motifs drawn from the natural world such as water, snow and clouds. On some kimono whole landscapes of mountains and streams are depicted. The numerous different ways in which such popular natural motifs are used on garments is testament to the skill of kimono designers, and of dyers and embroiderers.

Poems & stories

Elements of the natural world that appear on kimono usually have strong poetic associations, while more complex landscape scenes often refer to particular stories drawn either from classical literature or popular myths.While carrying an auspicious meaning, they also serve to demonstrate the literary discernment and cultural sensitivities of the wearer.Although such stories invariably involved people, it is relatively unusual to find human figures depicted on kimono. Instead there are objects which suggest their presence or recent departure, a pair of dropped fans, for example, alluding to lovers disturbed.

From the early 20th century increasingly graphic imagery was used on kimono. On garments for young boys in particular, symbols of Japan's modern and progressive present - cars, trains, aeroplanes and skyscrapers - became as popular as stories of the past. In the 1930s such motifs became increasingly nationalistic and militaristic.

Edo period (1615-1868)

Kimono, Japan, 1780-1830, crepe silk with paste-resist decoration (chaya-zome), stencilled imitation tie-dye (kata kanoko) and embroidery in silk and metallic thread. Museum no. FE.12-1983, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Edo period was one of unprecedented political stability, economic growth, and urban expansion. Kyoto, the old capital, remained the centre of aristocratic culture and luxury production while Edo, the new headquarters chosen by the Tokugawa shōgun (military ruler), developed from a small fishing port into one of the largest cities in the world. In Edo and elsewhere, a dynamic urban culture developed in which fashionable dress played a central role.

The primary consumers of sumptuous kimono were the samurai, the ruling military class.Yet it was the merchant and artisan classes, or chōnin, who benefited most from the peace and prosperity of the period. However, the rigid hierarchy of Tokugawa Japan meant that they could not use their wealth to improve their social status. Instead they had to find different outlets for their money, such as buying beautiful clothes. It was this new market that stimulated the great flowering of the textile arts in the Edo period. The kimono developed into a highly expressive means of personal display, an important indicator of the rising affluence and aesthetic sensibility of the chōnin.There were even fashion contests between the wives of the wealthiest merchants, who tried to outdo one another with ever more dazzling displays of splendid costume.Such excesses troubled the shogunate as they threatened to upset the strict social order and sumptuary laws that restricted the kind of fabrics, techniques and colours used by the chōnin were periodically issued.

Although the laws were not consistently enforced, leading to regular shifts between opulence and restraint, they did usher in certain changes. New techniques were developed and the use of subdued colours and fabrics became increasingly common. This was part of a new aesthetic known as iki, or elegant chic, in which anyone with real taste focussed on subtle details.Those with style and money also found other ways to circumvent the rules. It became very fashionable, for example, to use the highly coveted, but forbidden, colour red on undergarments and linings, for these were not covered by the restrictions.

Meiji period (1868-1912)

Kimono, Japan, 1870-1880, crepe silk (chirimen), paste-resist decoration (yuzen) and embroidery. Museum no. FE.29-1987, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In 1853 an American naval squadron arrived off the coast of Japan demanding that the country open its ports to western powers. This external pressure combined with internal unrest and led to revolution, the overthrow of the shōgun and the restoration of the Meiji Emperor in 1868. The imperial court moved to Edo, which was renamed Tokyo.

The new government realized that the only way Japan would be able to compete with the military and industrial might of the West was to transform itself along western lines. An unprecedented period of transformation was launched that was to affect all areas of life, including clothing. It was at this point that the word 'kimono', the thing worn, was coined to define T-shaped garments as opposed to western-style ones.

Some members of the elite adopted western dress because of its association with the concepts of civilisation, modernisation and progress that the Meiji government sought to promote. Dress also began to diverge along lines of place and gender as men started to wear business suits for work. While men usually changed into kimono when at home in the private sphere, women, who tended to inhabit only the domestic space, continued to wear kimono most of the time. Interestingly, Japan's textile industry was one of the first to adopt western science and technology. Using new techniques silk fabric was produced in greater qualities and at reasonable prices. Many women could afford to buy silk kimono for the first time and, with the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the sumptuary laws, were not forbidden from wearing them.

The 'opening' of Japan aroused enormous interest in the West and the flood of information and goods that subsequently reached Europe and America led to a craze for all things Japanese. Kimono were exported to the West, and by the 1870s were available to buy in shops such as Liberty's in London.

The interwar years

Kimono, Japan, 1934, silk crepe with resist-dyeing and embroidery. Museum no. FE.138-2002, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Taishō period (1912-1926) was one of confidence and optimism in Japan. Industrial development was stimulated by the First World War, economic prosperity being matched by political democratisation. It was a period of great urban growth, particularly in the capital, Tokyo. People moved to the suburbs, commuting on expanding railway networks to new types of office and factory jobs. Women entered the work force in large numbers, employed as typists, bank clerks, bus conductors and shop assistants. These workers were the consumers of a new mass urban culture that centred on the café, the cinema and the department store.

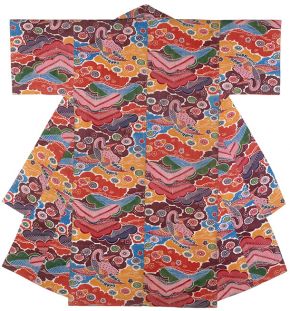

Although western-style clothes gained popularity among women, the kimono continued to be worn. The traditional cut of the garment remained the same, but the motifs were dramatically enlarged and new designs appeared, inspired by western styles such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Their striking patterns reflected the confident spirit of the age and provided an exuberant visual statement for the modern, independent, urban woman of the Taishō and early Shōwa periods (1926-1989).

In creating these boldly patterned and brilliantly coloured kimono, textile designers benefited from technological advances made during the late 19th century. Power-operated spinning machines and jacquard looms introduced from Europe had speeded up production and lowered costs, while chemical dyes allowed for the creation of dazzling colours. In the early 20th century new types of silk and innovative patterning techniques were also developed, making relatively inexpensive, highly fashionable garments available to more people than ever before. These vibrant kimono styles remained popular until the 1950s.

Kimono today

Kimono, 'Spring', Matsuda Eriko, Japan, 2005-2006. Museum no. FE.145-2006, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Since the end of the Second World War western-style clothing has been the everyday wear of most Japanese. The older generation often continue to wear kimono, as do geisha, actors, and those serving in traditional restaurants or engaged in activities such the tea ceremony. Generally however, kimono are only worn at a limited number of formal occasions and there are fairly rigid guidelines about what type of garment is appropriate for what event.

Kimono are also very expensive. If this limits the wearing of them, it also proclaims their high cultural value. Indeed, the garment may be worn much less, but its symbolic importance has grown. As Japan has come to define itself within the western world since the late 19th century, the kimono has come to mark a boundary with the foreign, to stand for the essence that is Japanese. This is reflected in the fact that most contemporary textile designers working with traditional techniques still use the kimono as the primary format for their artistic expression.

The 21st century, however, has witnessed something of a kimono renaissance. Elegant kimono in beautiful modern fabrics can be seen increasingly on the streets of Japan, while second-hand kimono are becoming popular with the young, who often re-style them or combine them with other items of dress. The resurgence of interest in kimono is particularly apparent in the summer, when department stores are full of yukata (summer kimono), which are much simpler to wear than formal garments. After the Second World War kimono were often viewed as a product of Japan's feudal past or a symbol of woman's oppression, but today they are just another choice in a woman's - and even occasionally a man's - wardrobe. They are an item of fashion, just as they were in their Edo heyday.

No comments:

Post a Comment