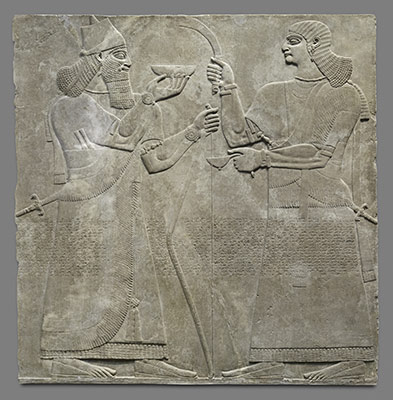

Relief panel

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 883–859 B.C.

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Gypsum alabaster

Dimensions: 92 1/4 x 92 x 4 1/2 in. (234.3 x 233.7 x 11.4 cm)

Classification: Stone-Reliefs-Inscribed

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932

Accession Number: 32.143.4

Description

This relief, from the palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (r. ca. 883-859 B.C.), depicts a king, probably Ashurnasirpal himself, and an attendant. The two larger-than-life-sized figures are carved in low relief, and as with other reliefs in the palace featuring the image of the king, the carving is particularly fine and shows special attention to detail. The panel joins a second relief (32.143.6, see ‘Additional Images’ above) that shows a further attendant, also facing the king, and a winged supernatural protective figure. Together, the two panels show the king flanked by his human courtiers, just as in other scenes he or the Assyrian Sacred Tree are flanked by human and eagle-headed winged guardian figures.

The king is immediately identifiable by his crown, a distinctive truncated cone with a smaller cone emerging from the center, with a long ‘streamer’ hanging from its back. He is also recognizable by his luxuriant beard, and in the relief’s original state would have been further distinguished by his clothing, more elaborately embroidered than that of any other figure. The pigment that originally colored these reliefs is now lost, but the embroidery is still faintly visible in the form of fine inscised lines made by the sculptors over most areas of the king’s clothing. The king wears elaborate jewelry, including rosette bracelets, thick armlets worn above the elbow, large pendant earrings, and a necklace whose beads and spacers would probably have consisted of semiprecious stones and gold. The king carries a sword on his left hip, as well as two daggers tucked into his clothing, and in his left hand holds the tip of a bow. In his right hand, balanced on his fingertips, is a shallow bowl. In other reliefs the bowl contains wine and is used for pouring libations, for example on the bodies of slain animals following a royal hunt. Here, however, there is no apparent object for the libation. The relief comes from an area of the palace that seems to have held sarcophagi and might have been devoted to the cult of royal ancestors, and one possibility is that the libation is here being poured for the dead. For similar reasons, while it is normally thought that all such images of the king represent Ashurnasirpal, it has also been suggested that some may represent ancestral kings.

The second figure on the relief is beardless, and probably represents a eunuch. He is richly dressed, with jewelry including rosette bracelets, armbands, a collar of beads, probably of semiprecious stone with gold spacers, pendant earrings, and a crescent-shaped pectoral. At the ends of his short sleeves are bands of incised plant motifs representing embroidery; another incised band below the waist shows further plants but also birds, possibly ostriches. He carries a sword whose scabbard, like the king's, ends in the image of two roaring lions. At the sword's hilt another lion head can be seen; an object in the Metropolitan Museum's collection may be just such a hilt (54.117.20). In his right hand the eunuch holds a fly-whisk whose handle is carved in the shape of a ram's head. The object in his left hand may be an oil lamp, though it has also been suggested that it might be a ladle to replenish the wine in the bowl held by the king. Its handle terminates in the head of a snake, or more likely a fantastic composite creature, called Mushhushshu, associated with the god Ashur.

Furniture plaque carved in high relief with two Egyptianizing figures flanking a volute tree

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 9th–8th century B.C.

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Ivory

Dimensions: H. 4 7/8 x W. 3 1/16 x Th. 7/16 in. (12.4 x 7.7 x 1.1 cm)

Classification: Ivory/Bone-Reliefs-Inscribed

Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1962

Accession Number: 62.269.3

Description

This rectangular plaque is carved in high relief with several features in the round and depicts two male figures flanking a stylized tree with voluted palmette branches emerging from its base. It was found with four other ivory plaques with similar imagery in a storeroom at Fort Shalmaneser, a royal building at Nimrud that was probably used to store tribute and booty collected by the Assyrians while on military campaign. Because of its skillful carving technique, symmetrical composition, and abundance of Egyptian forms, this piece has been attributed to the Phoenician style. A winged sun disc crowns and spans the length of the scene, above which emerge ten frontally facing uraei (mythical, fire-spitting serpents) set in a row, each crowned by sun discs. The Egyptianizing figures wear pschent crowns (the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt), beards, and wesekh broad collars with pendant droplets. They are clad in long, elaborately incised, pleated skirts that cover short, shendyt kilts tied with belts embroidered with a central chevron-patterned panel and two uraei projecting from either side, framed by decorative flaps. In their lowered hands, both figures hold a Phoenician-type spouted ewer and touch ram-headed scepters crowned by sun discs, held in their upraised hands, to the upper volute of the central tree. Two dowel holes, drilled deeply into either side of the sun disc, would have aided in securing this plaque to a frame by means of dowels, likely as part of a piece of furniture. The West Semitic letters Tav and Bet are inscribed into the reverse. Known as fitter’s marks, they would have served as guides to aid the craftsperson in the piece-by-piece assembly of the piece of furniture to which this plaque originally belonged.

Built by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, the palaces and storerooms of Nimrud housed thousands of pieces of carved ivory. Most of the ivories served as furniture inlays or small precious objects such as boxes. While some of them were carved in the same style as the large Assyrian reliefs lining the walls of the Northwest Palace, the majority of the ivories display images and styles related to the arts of North Syria and the Phoenician city-states. Phoenician style ivories are distinguished by their use of imagery related to Egyptian art, such as sphinxes and figures wearing pharaonic crowns, and the use of elaborate carving techniques such as openwork and colored glass inlay. North Syrian style ivories tend to depict stockier figures in more dynamic compositions, carved as solid plaques with fewer added decorative elements. However, some pieces do not fit easily into any of these three styles. Most of the ivories were probably collected by the Assyrian kings as tribute from vassal states, and as booty from conquered enemies, while some may have been manufactured in workshops at Nimrud. The ivory tusks that provided the raw material for these objects were almost certainly from African elephants, imported from lands south of Egypt, although elephants did inhabit several river valleys in Syria until they were hunted to extinction by the end of the eighth century B.C.

Built by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, the palaces and storerooms of Nimrud housed thousands of pieces of carved ivory. Most of the ivories served as furniture inlays or small precious objects such as boxes. While some of them were carved in the same style as the large Assyrian reliefs lining the walls of the Northwest Palace, the majority of the ivories display images and styles related to the arts of North Syria and the Phoenician city-states. Phoenician style ivories are distinguished by their use of imagery related to Egyptian art, such as sphinxes and figures wearing pharaonic crowns, and the use of elaborate carving techniques such as openwork and colored glass inlay. North Syrian style ivories tend to depict stockier figures in more dynamic compositions, carved as solid plaques with fewer added decorative elements. However, some pieces do not fit easily into any of these three styles. Most of the ivories were probably collected by the Assyrian kings as tribute from vassal states, and as booty from conquered enemies, while some may have been manufactured in workshops at Nimrud. The ivory tusks that provided the raw material for these objects were almost certainly from African elephants, imported from lands south of Egypt, although elephants did inhabit several river valleys in Syria until they were hunted to extinction by the end of the eighth century B.C.

Human-headed winged lion (lamassu)

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 883–859 B.C.

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Gypsum alabaster

Dimensions: H. 122 1/2 x W. 24 1/2 x D. 109 in., 15999.8 lb. (311.2 x 62.2 x 276.9 cm, 7257.4 kg)

Classification: Stone-Reliefs-Inscribed

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932

Accession Number: 32.143.2

Description

From the ninth to the seventh century B.C., the kings of Assyria ruled over a vast empire centered in northern Iraq. The great Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 B.C.), undertook a vast building program at Nimrud, ancient Kalhu. Until it became the capital city under Ashurnasirpal, Nimrud had been no more than a provincial town.

The new capital occupied an area of about nine hundred acres, around which Ashurnasirpal constructed a mudbrick wall that was 120 feet thick, 42 feet high, and five miles long. In the southwest corner of this enclosure was the acropolis, where the temples, palaces, and administrative offices of the empire were located. In 879 B.C. Ashurnasirpal held a festival for 69,574 people to celebrate the construction of the new capital, and the event was documented by an inscription that read: "the happy people of all the lands together with the people of Kalhu—for ten days I feasted, wined, bathed, and honored them and sent them back to their home in peace and joy."

The so-called Standard Inscription that ran across the surface of most of the reliefs described Ashurnasirpal's palace: "I built thereon [a palace with] halls of cedar, cypress, juniper, boxwood, teak, terebinth, and tamarisk [?] as my royal dwelling and for the enduring leisure life of my lordship." The inscription continues: "Beasts of the mountains and the seas, which I had fashioned out of white limestone and alabaster, I had set up in its gates. I made it [the palace] fittingly imposing." Among such stone beasts is the human-headed, winged lion pictured here. The horned cap attests to its divinity, and the belt signifies its power. The sculptor gave these guardian figures five legs so that they appear to be standing firmly when viewed from the front but striding forward when seen from the side. Lamassu protected and supported important doorways in Assyrian palaces.

The new capital occupied an area of about nine hundred acres, around which Ashurnasirpal constructed a mudbrick wall that was 120 feet thick, 42 feet high, and five miles long. In the southwest corner of this enclosure was the acropolis, where the temples, palaces, and administrative offices of the empire were located. In 879 B.C. Ashurnasirpal held a festival for 69,574 people to celebrate the construction of the new capital, and the event was documented by an inscription that read: "the happy people of all the lands together with the people of Kalhu—for ten days I feasted, wined, bathed, and honored them and sent them back to their home in peace and joy."

The so-called Standard Inscription that ran across the surface of most of the reliefs described Ashurnasirpal's palace: "I built thereon [a palace with] halls of cedar, cypress, juniper, boxwood, teak, terebinth, and tamarisk [?] as my royal dwelling and for the enduring leisure life of my lordship." The inscription continues: "Beasts of the mountains and the seas, which I had fashioned out of white limestone and alabaster, I had set up in its gates. I made it [the palace] fittingly imposing." Among such stone beasts is the human-headed, winged lion pictured here. The horned cap attests to its divinity, and the belt signifies its power. The sculptor gave these guardian figures five legs so that they appear to be standing firmly when viewed from the front but striding forward when seen from the side. Lamassu protected and supported important doorways in Assyrian palaces.

No comments:

Post a Comment