Rome has been seized and occupied by enemies so many times that it is hard to come up with an exact number. After each sacking, however terrible, Rome rose again, phoenix-like. Evidence of these assaults can still be seen today.

387 BC

The Gauls’ attack on Rome more than 24 centuries ago is still the best remembered, thanks to the stories of the later Roman historian Livy. In them he recounts the Romans’ self-sacrifice and no-nonsense courage as, while the city below burns, they defend their last redoubt on the Capitoline Hill. The best known story is that of the geese, whose quacks in the night warn the Romans of a Gallic sneak attack. Yet visitors will look in vain for any signs of this struggle, and with good reason. Archaeologists have failed to find a burnt layer or any other evidence of damage from this time. Careful studies of the sources suggest an explanation. Livy’s stories were patriotic guff. Many historians now suspect that the Romans never held out on the Capitoline. They surrendered to the Gauls and did so promptly, bribing them with gold to go away. If it wasn’t a heroic choice it was a shrewd one. Their city preserved, and stung by the disaster, the Romans rose to become the superpower of the Mediterranean.

410 AD

Rome had much more to lose eight centuries later, in 410 AD. By then it had grown from a small town to a vast metropolis and its population was 10 or 20 times greater. The attack of 410 was a devastating psychological blow to the Romans, who had thought their city invulnerable, but things could have been far worse. In a three-day sacking only a few buildings appear to have been burned, mostly in the Forum area. Then again Alaric, the barbarian Visigoths’ leader, had no wish to destroy Rome. He wanted to use it as a bargaining chip to help him get a homeland within the Roman Empire for his people. One building that was attacked was Basilica Amelia―an ancient mall with many bankers’ stalls. All that remains now is its floor. This is fenced off but still visible are a number of small green discs. These are coins that melted into the paving as the building burned. If Rome was fairly lucky in 410, that would change. In 455 the city suffered a much more destructive attack by the Vandals, raiding from their kingdom in Tunisia. A century later Rome suffered extensive damage when it was caught in the middle of 20-year struggle between the Ostrogoths and the Byzantine Empire, when it changed hands several times and was briefly empty of any inhabitants.

1084

Eleventh-century Rome was a medieval city like no other. Rich Romans lived in homes built into classical ruins― abandoned theaters, stadiums and long dry baths. The Colosseum was the city’s largest housing complex. In 1084 the Norman ruler of Southern Italy, Robert Guiscard, attacked Rome to rescue Pope Gregory VII, who the Romans had fallen out with, and who was hiding out in the fortress of Castel Sant’Angelo. Today visitors can still see the stretch of wall, just by Porta Latina, where the Normans are thought to have broken in, scaling the wall with ladders at dawn. Other telltale signs of the attack are found in a number of medieval churches that were repaired or rebuilt soon after this time. They replaced churches that had been strong points in the city, and were burned by the Normans to prevent them being used to block their retreat. Unlike most assaults on Rome, which involved prolonged sieges and poorly organized attacks, Guiscard’s assault was a highly professional operation, worthy of a special forces unit, and it may have been completed with the successful rescue of the pope in a matter of hours. Aside from a handful of churches Rome was little damaged. Once again the city had been lucky.

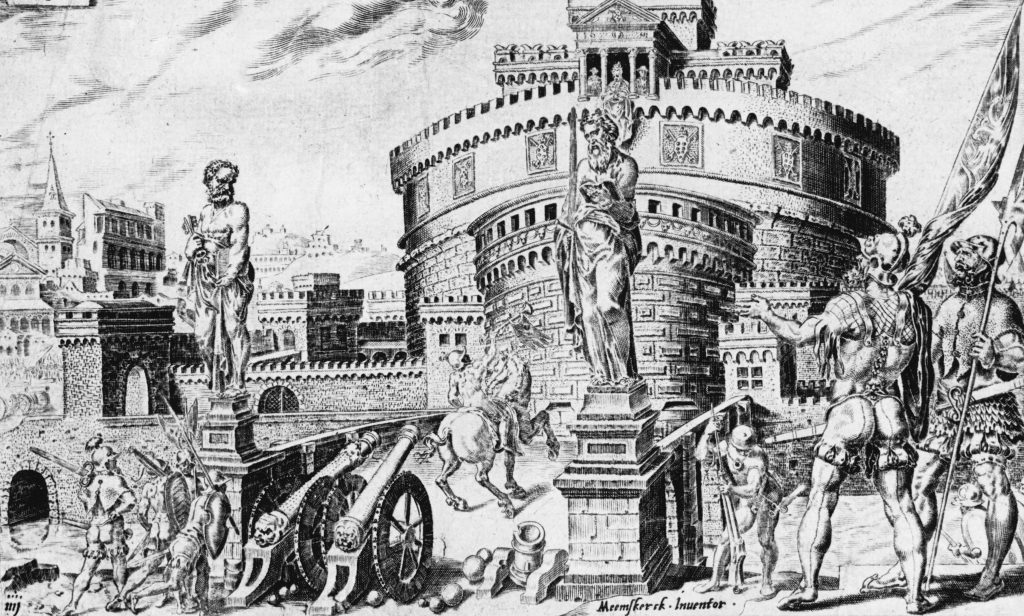

Siege of Rome by the forces of Emperor Charles V of Spain, 1527. (Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

1527

This was one of the most shocking and horrific assaults on Rome―and we know about it in great detail. For 10 months the city was occupied by the mutinous army of Emperor Charles V, killing, raping, kidnapping and torturing Romans. Thousands died. Matters were made worse because a large portion of the soldiers were Lutherans who felt a passionate hatred of Rome’s Churchmen. The altar of St. Peter’s was piled with corpses of those who had sought sanctuary there and for months the basilica was used as a stables by the Imperial cavalry. Scores of clerics were branded, tortured or castrated. Today visitors can see the Castel Sant’Angelo, where Pope Clement VII escaped to, safe from the horror below. Of the assault itself, signs are few. In the Vatican Palace one can still see, scratched into plaster of a fresco by Raphael, the name Luther, written by one of Charles V’s soldiers. And there is the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo’s ceiling paintings seem light and optimistic compared to disturbing, broody masterpiece, The Last Judgement. He painted the ceiling well before the sack but produced the Last Judgement after its terrors. One of the clearest signs of the 1527 sacking, though, is absence. Many European cities still have a few medieval timber houses but not Rome. Before the 1527 attack it had had thousands. Charles V’s soldiers ripped out timbers, doors and frames to burn as firewood, speeding Rome’s transformation to the city of fine stone homes.

A view from one of the 150 Allied B17 Flying Fortress bombers attacking the San Lorenzo freight yard and steel factory in Rome on July 19, 1943. (Credit: Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

1943-44

Here was another long and grueling occupation—eight months—this time by Nazi Germans and Italian Fascists. The assault left many traces though they require some searching out. In the cloisters of San Lorenzo church one can find part of a bomb, one of many that were dropped by Allied planes on July 19, 1943, damaging the San Lorenzo district and the church. Rome is not usually thought of as a city that suffered from air attack, largely because the center was little affected, but the outskirts were badly hit. Close to old railway yards one can find incongruously modern buildings in street of older ones, marking the spots where bombs struck. Some 7000 Romans died in the bombing. In Rome’s pavements, especially around the old Jewish Ghetto, there are also many small bronze tablets among the cobblestones, each bearing a name. These remember the homes from where Jewish Romans—some 2,000—were deported during the occupation. Few returned. On the via Rasella, close to the Trevi Fountain, small, jagged holes are evident in the walls of apartment blocks. These were left by a bomb that was detonated by Rome’s highly active resistance movement in March 1944, killing 33 German soldiers.Just south of Rome near the Appia Antica, one can visit a memorial at the Fosse Ardeatina caves, where 335 members of the resistance, Jewish Romans and others, who simply had the bad luck of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, were shot in reprisal for the bombing. Perhaps the most haunting relic of this time, though, is on Via Tasso, near the Lateran. Here the building used by the SS as a torture center has been carefully preserved as a Museum of the Liberation of Rome. As well as messages scratched into the walls by those held there, one can see windows that were bricked up, so neighbors could not see what was done or hear their cries. The museum, which is regularly visited by school groups, is kept both in memory of those who suffered and died there, and as a warning, so that nothing like it might ever happen again.

A view from one of the 150 Allied B17 Flying Fortress bombers attacking the San Lorenzo freight yard and steel factory in Rome on July 19, 1943.

No comments:

Post a Comment