Founded in the 3rd millennium B.C., Damascus is one of the oldest cities

in the Middle East. In the Middle Ages, it was the centre of a

flourishing craft industry, specializing in swords and lace. The city

has some 125 monuments from different periods of its history – one of

the most spectacular is the 8th-century Great Mosque of the Umayyads,

built on the site of an Assyrian sanctuary.

Great Mosque of the Umayyads

Great Mosque of the Umayyads

Pair of doors, 9th

century; cAbbasid Iraq

Pair of doors, 9th

century; cAbbasid Iraq

Carved wood; 87 3/4 x 41 1/4 in. (222.9 x 104.7 cm)

Description: These doors clearly show the beveled style (the symetrical abstract floral motiff seen

on both doors) and were most likely painted and gilded. These doors were said to have been found

at the city of Takrit, but most likely were really from the city of Samarra

BACKGROUND INFORMATION-- The City of Samarra

Samarra is located in Iraq about 125 miles upriver from Baghdad. It was founded in 836 CE by the

Abbasid caliph al-Mutasim (r. 836-42) to accomodate some of his unruly soldiers who had been causing

problems and making life uneasy in Baghdad. Samarra ended up being the second (and temporary) capital

of the Abbasid Caliphates until the end of the ninth century (around 883 CE)

Source of the picture of the doors

Leaf from a Qur’an

manuscript, late 9th–10th century

Leaf from a Qur’an

manuscript, late 9th–10th century

Possibly Syria

Ink, gold, and colors on vellum; 13 1/8 x 9 3/8 in. (33.3 x 23.8 cm)

Description: The angular kufic script of the document is moderated by the roundness of

several of the letters that resemble large black dots, while their inner blank spaces are

reduced to almost a needlepoint. The red marks on the document are meant to be used

as an aid to the reader of the manuscript. This artful page represents the amazing caligraphy

that existed around the time of the Abbasids.

Source of the picture of the leaf from a Quran manuscript

Bowl, 10th century Iraq

Bowl, 10th century Iraq

Composite body, luster-painted; Gr. H. 2 5/16 in. (6.2 cm), Max. Diam. 9 5/16 in. (23.7 cm)

Description: This bowl depicts a classic style of including stylized human figures. In this example of this

method, the bowl displays a seated man holding a beaker and flowering branch is enhanced by two birds

each hold a fish in their beaks but almost look like they are in fact, kissing.

Source of the picture of the bowl

Textile fragment, late 10th century; cAbbasid

Probably Iraq

Cotton, plain weave with painted inscription; 9 x 14 in. (22.9 x 35.6 cm)

Description: Simple painted brushtrokes are often seen in cotton textiles from the Islamic world during the Abbasids. The painted surface

employs the same Abbasid epigraphic style common in calligraphy. The inscription reads, "perfect blessing" and is repeated in an echo of the

flowing brushstroks. The final letter of the word "blessing" (baraka) is extended to punctuate more repetitions located about the main inscription.

It is believed that the pattern could have filled the length of the complete textile.

Source of the picture of the bowl

Leaf from an Arabic translation of the Materia Medica of Dioscorides ("The Pharmacy"), dated 1224

Iraq, Baghdad School

Colors and gilt on paper; 12.3 x 9 in. (31.4 x 22.9 cm)

Description: This folio is painted in the classic style of the Bagdad school with bright colors, sprightly figures

in contemporary local dress, as well as a blanced and 'bilaterally symmetrical' composition. The color of the leave,

a pale neutral brown, inforces the two-dimensionality of the picture

Source of the picture of the folio leaf

Panel, Marquetry, second half of 8th century; cAbbasid Egypt

Fig wood and bone; H. 18 3/4 in. (47.6 cm), W. 76 1/2 in. (194.3 cm)

Description: This fig-wood panel is inlaid with bone displays many decorative elements from the late antique period. The geometric motiffs show

the classic geometrical pattern commonly found in Abbasid art. The curved bone plaques in the center bear vine scrolls that display a more classical

lineage then the tile style which was probably influenced by Rome. While the piece was obviously influenced by other cultures, the geometric patterns

are classic of the Abbasid period.

Source of the picture of the panel

Master Suleiman (Iranian, Abbasid caliphate), Aquamanile in the Form of an Eagle,

180 A.H. / CE 796-797, bronze, silver,copper, 38 x 45 cm

Description: An aquamanile was used for carrying water. This specific aquamanile originally had a handle on top for carrying.

This piece displays the elborate work and beauty put into the art during the Abbasid Caliphate. The eagle form is exquisite, and

the precious medals and time put into the piece are astounding.

Source of the eagle

Art in the Abbasid Caliphate

"It is truly a privilege to be able to display LACMA’s exceptional collection of Islamic art from such a variety of world cultures here in Saudi Arabia,” said Fuad Al-Therman, Director of the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture. "Seeing our civilization depicted through these beautiful objects, and being able to share such valuable pieces of world and regional history with our visitors, is a great honor."

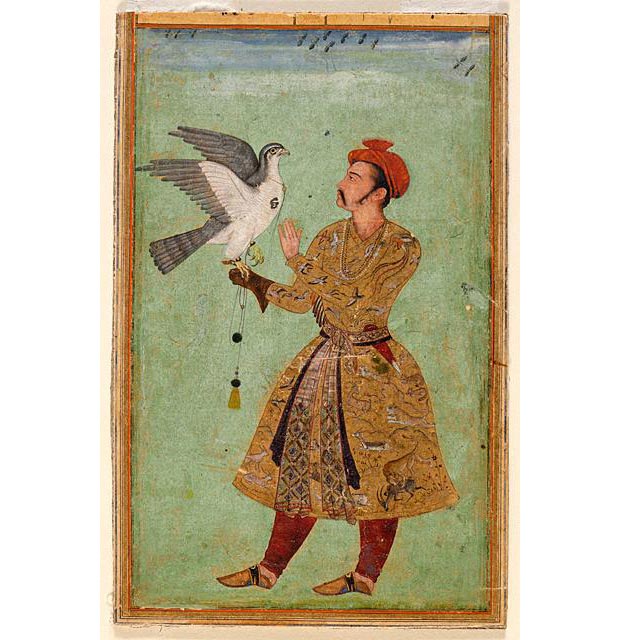

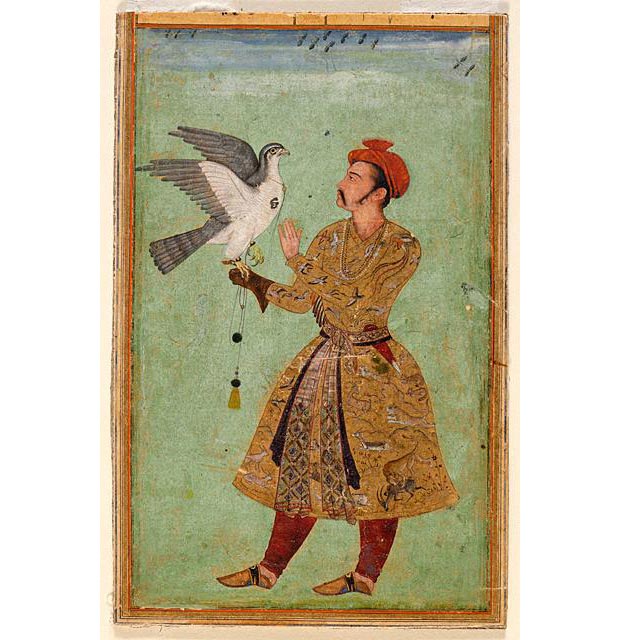

Prince with a Falcon / North India / LACMA - From the Nesli and Alice

Heeramaneck Collection / Museum Associates Purchase / Courtesy of LACMA

Prince with a Falcon / North India / LACMA - From the Nesli and Alice

Heeramaneck Collection / Museum Associates Purchase / Courtesy of LACMA

LACMA’s holdings in Islamic art comprise one of the most significant such collections worldwide. Over 130 works of art will be included in the two-year exhibition, most of which are the products of great urban centers such as Cairo, Damascus, Samarqand, Isfahan, Granada, Istanbul, Delhi, and Lahore. These luxury objects demonstrate the evident demand within Muslim society for both functionality and virtuosity. Such meticulously produced objects largely define the material culture of the ruling elite and privileged classes, in a period stretching well over a millennium and in an area extending from southern Spain to western Central Asia and northern India. Brilliantly glazed pottery and tiles, enameled and gilded glass, inlaid metalwork, carved ornamental stone and wood, lavish woven textiles, and vividly illuminated and superbly written manuscripts all absorbed the creative energies of artists, becoming highly developed art forms.

Among the masterworks from the collection to be presented in the exhibition are:

The Damascus room features beautifully painted and carved wood walls, an intricately inlaid stone wall fountain, and a spectacular arch formed of colorful plaster voussoirs. Perhaps because it was in storage for so many years and had never been reinstalled restored, the room is largely in its original, though aged, state, with one of the best-preserved painted surfaces—including bright pinks, oranges, blues and greens—of any similar room of the period. It will be unveiled to the public for the first time in the Center’s museum. Conservation of the Damascus Room is currently underway at LACMA. Additional support is provided by the Friends of Heritage Preservation, a private charitable group supporting cultural and historical preservation projects worldwide.

The Damascus room, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

The Damascus room, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

The Damascus room, detail, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

The Damascus room, detail, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

The Damascus room, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

The Damascus room, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

ʿAbbāsid Dynasty, second of the two great dynasties of the Muslim Empire of the Caliphate. It overthrew the Umayyad caliphate in ad 750 and reigned as the ʿAbbāsid caliphate until destroyed by the Mongol invasion in 1258.

The name is derived from that of the uncle of the Prophet Muḥammad, al-ʿAbbās (died c. 653), of the Hāshimite clan of the Quraysh tribe in Mecca. From c. 718, members of his family worked to gain control of the empire, and by skillful propaganda won much support, especially from Shīʿī Arabs and Persians in Khorāsān. Open revolt in 747, under the leadership of Abū Muslim, led to the defeat of Marwān II, the last Umayyad caliph, at the Battle of the Great Zāb River (750) in Mesopotamia and to the proclamation of the first ʿAbbāsid caliph, Abū al-ʿAbbās as-Saffāḥ.

Under the ʿAbbāsids the caliphate entered a new phase. Instead of focussing, as the Umayyads had done, on the West—on North Africa, the Mediterranean, and southern Europe—the caliphate now turned eastward. The capital was moved to the new city of Baghdad, and events in Persia and Transoxania were closely watched. For the first time the caliphate was not coterminous with Islām; in Egypt, North Africa, Spain, and elsewhere, local dynasties claimed caliphal status. With the rise of the ʿAbbāsids the base for influence in the empire became international, emphasizing membership in the community of believers rather than Arab nationality. Since much support for the ʿAbbāsids came from Persian converts, it was natural for the ʿAbbāsids to take over much of the Persian (Sāsānian) tradition of government. Support by pious Muslims likewise led the ʿAbbāsids to acknowledge publicly the embryonic Islāmic law and to profess to base their rule on the religion of Islām. Between 750 and 833 the ʿAbbāsids raised the prestige and power of the empire, promoting commerce, industry, arts, and science, particularly during the reigns of al-Manṣūr, Hārūn ar-Rashīd, and al-Maʾmūn. Their temporal power, however, began to decline when al-Muʿtaṣim introduced non-Muslim Berber, Slav, and especially Turkish mercenary forces into his personal army. Although these troops were converted to Islām, the base of imperial unity through religion was gone, and some of the new army officers quickly learned to control the caliphate through assassination of any caliph who would not accede to their demands.

The power of the army officers had already weakened through internal rivalries when the Iranian Būyids entered Baghdad in 945, demanding of al-Mustakfī (944–946) that they be recognized as the sole rulers of the territory they controlled. This event initiated a century-long period in which much of the empire was ruled by local secular dynasties. In 1055 the ʿAbbāsids were overpowered by the Seljuqs, who took what temporal power may have been left to the caliph but respected his position as religious leader, restoring the authority of the caliphate, especially during the reigns of al-Mustarshid (1118–35), al-Muqtafī, and an-Nāṣir. Soon after, in 1258, the dynasty fell during a Mongol siege of Baghdad.

Great Mosque of the Umayyads

Great Mosque of the Umayyads

Early Capitals of Islamic Culture: The Art and Culture of Umayyad Damascus and Abbasid Baghdad (650 - 950)

Capital,

9th century Abbasid Syria

Capital,

9th century Abbasid Syria

Carved alabaster; 13 3/4 x 15 1/4 in. (34.9 x 38.7 cm)

Description: This capital displays the beveled style common

in Abbasid art. The background and

foreground of this

piece may have become

indistinguishable, making this capital very distinct.This style,

developed in Samara , would represent the basis for

all developments in the future of the Islamic world.

Source

of the picture of the capital

Pair of doors, 9th

century; cAbbasid Iraq

Pair of doors, 9th

century; cAbbasid IraqCarved wood; 87 3/4 x 41 1/4 in. (222.9 x 104.7 cm)

Description: These doors clearly show the beveled style (the symetrical abstract floral motiff seen

on both doors) and were most likely painted and gilded. These doors were said to have been found

at the city of Takrit, but most likely were really from the city of Samarra

BACKGROUND INFORMATION-- The City of Samarra

Samarra is located in Iraq about 125 miles upriver from Baghdad. It was founded in 836 CE by the

Abbasid caliph al-Mutasim (r. 836-42) to accomodate some of his unruly soldiers who had been causing

problems and making life uneasy in Baghdad. Samarra ended up being the second (and temporary) capital

of the Abbasid Caliphates until the end of the ninth century (around 883 CE)

Source of the picture of the doors

Leaf from a Qur’an

manuscript, late 9th–10th century

Leaf from a Qur’an

manuscript, late 9th–10th centuryPossibly Syria

Ink, gold, and colors on vellum; 13 1/8 x 9 3/8 in. (33.3 x 23.8 cm)

Description: The angular kufic script of the document is moderated by the roundness of

several of the letters that resemble large black dots, while their inner blank spaces are

reduced to almost a needlepoint. The red marks on the document are meant to be used

as an aid to the reader of the manuscript. This artful page represents the amazing caligraphy

that existed around the time of the Abbasids.

Source of the picture of the leaf from a Quran manuscript

Bowl, 10th century Iraq

Bowl, 10th century IraqComposite body, luster-painted; Gr. H. 2 5/16 in. (6.2 cm), Max. Diam. 9 5/16 in. (23.7 cm)

Description: This bowl depicts a classic style of including stylized human figures. In this example of this

method, the bowl displays a seated man holding a beaker and flowering branch is enhanced by two birds

each hold a fish in their beaks but almost look like they are in fact, kissing.

Source of the picture of the bowl

Textile fragment, late 10th century; cAbbasid

Probably Iraq

Cotton, plain weave with painted inscription; 9 x 14 in. (22.9 x 35.6 cm)

Description: Simple painted brushtrokes are often seen in cotton textiles from the Islamic world during the Abbasids. The painted surface

employs the same Abbasid epigraphic style common in calligraphy. The inscription reads, "perfect blessing" and is repeated in an echo of the

flowing brushstroks. The final letter of the word "blessing" (baraka) is extended to punctuate more repetitions located about the main inscription.

It is believed that the pattern could have filled the length of the complete textile.

Source of the picture of the bowl

Leaf from an Arabic translation of the Materia Medica of Dioscorides ("The Pharmacy"), dated 1224

Iraq, Baghdad School

Colors and gilt on paper; 12.3 x 9 in. (31.4 x 22.9 cm)

Description: This folio is painted in the classic style of the Bagdad school with bright colors, sprightly figures

in contemporary local dress, as well as a blanced and 'bilaterally symmetrical' composition. The color of the leave,

a pale neutral brown, inforces the two-dimensionality of the picture

Source of the picture of the folio leaf

Panel, Marquetry, second half of 8th century; cAbbasid Egypt

Fig wood and bone; H. 18 3/4 in. (47.6 cm), W. 76 1/2 in. (194.3 cm)

Description: This fig-wood panel is inlaid with bone displays many decorative elements from the late antique period. The geometric motiffs show

the classic geometrical pattern commonly found in Abbasid art. The curved bone plaques in the center bear vine scrolls that display a more classical

lineage then the tile style which was probably influenced by Rome. While the piece was obviously influenced by other cultures, the geometric patterns

are classic of the Abbasid period.

Source of the picture of the panel

Master Suleiman (Iranian, Abbasid caliphate), Aquamanile in the Form of an Eagle,

180 A.H. / CE 796-797, bronze, silver,copper, 38 x 45 cm

Description: An aquamanile was used for carrying water. This specific aquamanile originally had a handle on top for carrying.

This piece displays the elborate work and beauty put into the art during the Abbasid Caliphate. The eagle form is exquisite, and

the precious medals and time put into the piece are astounding.

Source of the eagle

Art in the Abbasid Caliphate

Lamp / Egypt or Syria, mid 14th Century /

"This is a landmark project for the museum," said LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director Michael Govan. "We are delighted that masterworks from LACMA’s eminent collection are traveling to Saudi Arabia so that they can be shared with a broader audience, and enjoyed not only for their obvious surface beauty but also for the rich historical and cultural traditions from which they emerged. We are also gratified to have a spectacular and important Damascus room enter LACMA’s holdings—which already includes one of the world’s top collections of Islamic art—and we are especially grateful to the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture for their significant partnership to restore and conserve the room.""It is truly a privilege to be able to display LACMA’s exceptional collection of Islamic art from such a variety of world cultures here in Saudi Arabia,” said Fuad Al-Therman, Director of the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture. "Seeing our civilization depicted through these beautiful objects, and being able to share such valuable pieces of world and regional history with our visitors, is a great honor."

Prince with a Falcon / North India / LACMA - From the Nesli and Alice

Heeramaneck Collection / Museum Associates Purchase / Courtesy of LACMA

Prince with a Falcon / North India / LACMA - From the Nesli and Alice

Heeramaneck Collection / Museum Associates Purchase / Courtesy of LACMALACMA’s holdings in Islamic art comprise one of the most significant such collections worldwide. Over 130 works of art will be included in the two-year exhibition, most of which are the products of great urban centers such as Cairo, Damascus, Samarqand, Isfahan, Granada, Istanbul, Delhi, and Lahore. These luxury objects demonstrate the evident demand within Muslim society for both functionality and virtuosity. Such meticulously produced objects largely define the material culture of the ruling elite and privileged classes, in a period stretching well over a millennium and in an area extending from southern Spain to western Central Asia and northern India. Brilliantly glazed pottery and tiles, enameled and gilded glass, inlaid metalwork, carved ornamental stone and wood, lavish woven textiles, and vividly illuminated and superbly written manuscripts all absorbed the creative energies of artists, becoming highly developed art forms.

Among the masterworks from the collection to be presented in the exhibition are:

- An Ottoman box boldly decorated with tortoiseshell and mother-of-pearl, possibly intended to store a precious manuscript such as the Qur’an.

- A gold repoussé bracelet from Fatimid Syria, which was likely once part of a matching pair, perhaps for a bride’s dowry.

- An album painting from Mughal India of a magnificently dressed young prince with a falcon.

- An enameled and gilded glass lamp probably made for a Mamluk madrasa in Cairo and inscribed with a quotation from the Qur’an as well as the name of its patron.

The Damascus room

Dated 1766–67 and measuring 15’ x 20’ (6.096 x 4.572 m), this largely complete interior served as a reception room, where the head of the family entertained honored guests. Such lavishly decorated rooms opened out to ornate stone courtyards in the well-to-do homes of Damascus. With the modernization and growth of the city, many historic homes were demolished, but occasionally their sumptuous interiors were spared, as was the case with the LACMA room. It was dismantled intact from a courtyard home in the al-Bahsa quarter of Damascus, which was torn down in 1978 to make way for a road; soon after, the room was exported from Syria to Beirut, Lebanon, where it remained for over 30 years.The Damascus room features beautifully painted and carved wood walls, an intricately inlaid stone wall fountain, and a spectacular arch formed of colorful plaster voussoirs. Perhaps because it was in storage for so many years and had never been reinstalled restored, the room is largely in its original, though aged, state, with one of the best-preserved painted surfaces—including bright pinks, oranges, blues and greens—of any similar room of the period. It will be unveiled to the public for the first time in the Center’s museum. Conservation of the Damascus Room is currently underway at LACMA. Additional support is provided by the Friends of Heritage Preservation, a private charitable group supporting cultural and historical preservation projects worldwide.

The Damascus room, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

The Damascus room, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA The Damascus room, detail, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

The Damascus room, detail, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA The Damascus room, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

The Damascus room, 1766–67/1181 AH / Photo © 2014 Museum Associates/LACMA / Courtesy of LACMA

The name is derived from that of the uncle of the Prophet Muḥammad, al-ʿAbbās (died c. 653), of the Hāshimite clan of the Quraysh tribe in Mecca. From c. 718, members of his family worked to gain control of the empire, and by skillful propaganda won much support, especially from Shīʿī Arabs and Persians in Khorāsān. Open revolt in 747, under the leadership of Abū Muslim, led to the defeat of Marwān II, the last Umayyad caliph, at the Battle of the Great Zāb River (750) in Mesopotamia and to the proclamation of the first ʿAbbāsid caliph, Abū al-ʿAbbās as-Saffāḥ.

Under the ʿAbbāsids the caliphate entered a new phase. Instead of focussing, as the Umayyads had done, on the West—on North Africa, the Mediterranean, and southern Europe—the caliphate now turned eastward. The capital was moved to the new city of Baghdad, and events in Persia and Transoxania were closely watched. For the first time the caliphate was not coterminous with Islām; in Egypt, North Africa, Spain, and elsewhere, local dynasties claimed caliphal status. With the rise of the ʿAbbāsids the base for influence in the empire became international, emphasizing membership in the community of believers rather than Arab nationality. Since much support for the ʿAbbāsids came from Persian converts, it was natural for the ʿAbbāsids to take over much of the Persian (Sāsānian) tradition of government. Support by pious Muslims likewise led the ʿAbbāsids to acknowledge publicly the embryonic Islāmic law and to profess to base their rule on the religion of Islām. Between 750 and 833 the ʿAbbāsids raised the prestige and power of the empire, promoting commerce, industry, arts, and science, particularly during the reigns of al-Manṣūr, Hārūn ar-Rashīd, and al-Maʾmūn. Their temporal power, however, began to decline when al-Muʿtaṣim introduced non-Muslim Berber, Slav, and especially Turkish mercenary forces into his personal army. Although these troops were converted to Islām, the base of imperial unity through religion was gone, and some of the new army officers quickly learned to control the caliphate through assassination of any caliph who would not accede to their demands.

The power of the army officers had already weakened through internal rivalries when the Iranian Būyids entered Baghdad in 945, demanding of al-Mustakfī (944–946) that they be recognized as the sole rulers of the territory they controlled. This event initiated a century-long period in which much of the empire was ruled by local secular dynasties. In 1055 the ʿAbbāsids were overpowered by the Seljuqs, who took what temporal power may have been left to the caliph but respected his position as religious leader, restoring the authority of the caliphate, especially during the reigns of al-Mustarshid (1118–35), al-Muqtafī, and an-Nāṣir. Soon after, in 1258, the dynasty fell during a Mongol siege of Baghdad.

No comments:

Post a Comment