But the Jutes were not the only newcomers to Britain during this period. Other Germanic tribes soon began to make the short journey across the North Sea. The Angles (from a region called Angeln, the spur of land which connects modern Denmark with Germany) gradually began to settle in increasing numbers on the east coast of Britain, particularly in the north and East Anglia. The Frisian people, from the marshes and islands of northern Holland and western Germany, also began to encroach on the British mainland from about 450 AD onwards. Still later, from the 470s, the war-like Saxons (from the Lower Saxony area of north-western Germany) made an increasing number of incursions into the southern part of the British mainland. Over time, these Germanic tribes began to establish permanent bases and to gradually displace the native Celts.

The influx of Germanic people was more of a gradual encroachment over several generations than an invasion proper, but these tribes between them gradually colonized most of the island, with the exception of the more remote areas, which remained strongholds of the original Celtic people of Britain. Originally sea-farers, they began to settle down as farmers, exploiting the rich English farmland. The rather primitive newcomers were if anything less cultured and civilized than the local Celts, who had held onto at least some parts of Roman culture. No love was lost between the two peoples, and there was little integration between them: the Celts referred to the European invaders as “barbarians” (as they had previously been labelled themselves); the invaders referred to the Celts as weales (slaves or foreigners), the origin of the name Wales.

The Germanic tribes settled in seven smaller kingdoms, known as the Heptarchy: the Saxons in Essex, Wessex and Sussex; the Angles in East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria; and the Jutes in Kent. Evidence of the extent of their settlement can be found in the number of place names throughout England ending with the Anglo-Saxon “-ing” meaning people of (e.g. Worthing, Reading, Hastings), “-ton” meaning enclosure or village (e.g. Taunton, Burton, Luton), “-ford” meaning a river crossing (e.g. Ashford, Bradford, Watford) “-ham” meaning farm (e.g. Nottingham, Birmingham, Grantham) and “-stead” meaning a site (e.g. Hampstead). Although the various different kingdoms waxed and waned in their power and influence over time, it was the war-like and pagan Saxons that gradually became the dominant group. The new Anglo-Saxon nation, once known in antiquity as Albion and then Britannia under the Romans, nevertheless became known as Anglaland or Englaland (the Land of the Angles), later shortened to England, and its emerging language as Englisc (now referred to as Old English or Anglo-Saxon, or sometimes Anglo-Frisian). It is impossible to say just when English became a separate language, rather than just a German dialect, although it seems that the language began to develop its own distinctive features in isolation from the continental Germanic languages, by around 600AD. Over time, four major dialects of Old English gradually emerged: Northumbrian in the north of England, Mercian in the midlands, West Saxon in the south and west, and Kentish in the southeast. |

The Celts and the early Anglo-Saxons used an alphabet of runes, angular characters originally developed for scratching onto wood or stone. The first known written English sentence, which reads "This she-wolf is a reward to my kinsman", is an Anglo-Saxon runic inscription on a gold medallion found in Suffolk, and has been dated to about 450-480 AD. The early Christian missionaries introduced the more rounded Roman alphabet (much as we use today), which was easier to read and more suited for writing on vellum or parchment. The Anglo-Saxons quite rapidly adopted the new Roman alphabet, but with the addition of letters such as The Latin language the missionaries brought was still only used by the educated ruling classes and Church functionaries, and Latin was only a minor influence on the English language at this time, being largely restricted to the naming of Church dignitaries and ceremonies (priest, vicar, altar, mass, church, bishop, pope, nun, angel, verse, baptism, monk, eucharist, candle, temple and presbyter came into the language this way). However, other more domestic words (such as fork, spade, chest, spider, school, tower, plant, rose, lily, circle, paper, sock, mat, cook, etc) also came into English from Latin during this time, albeit substantially altered and adapted for the Anglo-Saxon ear and tongue. More ecclesiastical Latin loanwords continued to be introduced, even as late as the 11th Century, including chorus, cleric, creed, cross, demon, disciple, hymn, paradise, prior, sabbath, etc.

|

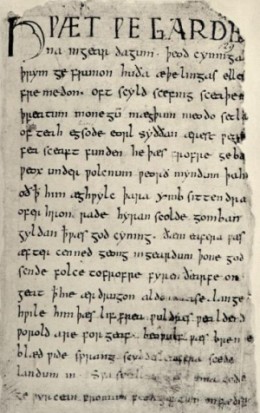

“Beowulf” may have been written any time between the 8th and the early 11th Century by an unknown author or authors, or, most likely, it was written in the 8th Century and then revised in the 10th or 11th Century. It was probably originally written in Northumbria, although the single manuscript that has come down to us (which dates from around 1000) contains a bewildering mix of Northumbrian, West Saxon and Anglian dialects. The 3,182 lines of the work shows that Old English was already a fully developed poetic language by this time, with a particular emphasis on alliteration and percussive effects. Even at this early stage (before the subsequent waves of lexical enrichment), the variety and depth of English vocabulary, as well as its predilection for synonyms and subtleties of meanings, is evident. For example, the poem uses 36 different words for hero, 20 for man, 12 for battle and 11 for ship. There are also many interesting "kennings" or allusive compound words, such as hronrad (literally, whale-road, meaning the sea), banhus (bone-house, meaning body) and beadoleoma (battle-light, meaning sword). Of the 903 compound nouns in “Beowulf”, 578 are used once only, and 518 of them are known only from this one poem. Old English was a very complex language, at least in comparison with modern English. Nouns had three genders (male, female and neuter) and could be inflected for up to five cases. There were seven classes of “strong” verbs and three of “weak” verbs, and their endings changed for number, tense, mood and person. Adjectives could have up to eleven forms. Even definite articles had three genders and five case forms as a singular and four as a plural. Word order was much freer than today, the sense being carried by the inflections (and only later by the use of propositions). Although it looked quite different from modern English on paper, once the pronunciation and spelling rules are understood, many of its words become quite familiar to modern ears. Many of the most basic and common words in use in English today have their roots in Old English, including words like water, earth, house, food, drink, sleep, sing, night, strong, the, a, be, of, he, she, you, no, not, etc. Interestingly, many of our common swear words are also of Anglo-Saxon origin (including tits, fart, shit, turd, arse and, probably, piss), and most of the others were of early medieval provenance. Care should be taken, though, with what are sometimes called "false friends", words that appear to be similar in Old English and modern English, but whose meanings have changed, words such as wif (wife, which originally meant any woman, married or not), fugol (fowl, which meant any bird, not just a farmyard one), sona (soon, which meant immediately, not just in a while), won (wan, which meant dark, not pale) and fæst (fast, which meant fixed or firm, not rapidly). During the 6th Century, for reasons which are still unclear, the Anglo-Saxon consonant cluster "sk" changed to "sh", so that skield became shield. This change affected all "sk" words in the language at that time, whether recent borrowings from Latin (e.g. disk became dish) or ancient aboriginal borrowings (e.g. skip became ship). Any modern English words which make use of the "sk" cluster came into the language after the 6th Century (i.e. after the sound change had ceased to operate), mainly, as we will see below, from Scandinavia. Then, around the 7th Century, a vowel shift took place in Old English pronunciation (analogous to the Great Vowel Shift during the Early Modernperiod) in which vowels began to be pronouced more to the front of the mouth. The main sound affected was "i", hence its common description as "i-mutation" or "i-umlaut" (umlaut is a German term meaning sound alteration). As part of this process, the plurals of several nouns also started to be represented by changed vowel pronunciations rather than changes in inflection. These changes were sometimes, but not always, reflected in revised spellings, resulting in inconsistent modern words pairings such as foot/feet, goose/geese, man/men, mouse/mice, as well as blood/bleed, foul/filth, broad/breadth, long/length, old/elder, whole/hale/heal/health, etc.

|

Viking expansion was finally checked by Alfred the Great and, in 878, a treaty between the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings established the Danelaw, splitting the country along a line roughly from London to Chester, giving the Norsemen control over the north and east and the Anglo-Saxons the south and west. Although the Danelaw lasted less than a century, its influence can be seen today in the number of place names of Norse origin in northern England (over 1,500), including many place names ending in “-by”, “-gate”, “-stoke”, “-kirk”, “-thorpe”, “-thwaite”, “-toft” and other suffixes (e.g. Whitby, Grimsby, Ormskirk, Scunthorpe, Stoke Newington, Huthwaite, Lowestoft, etc), as well as the “-son” ending on family names (e.g. Johnson, Harrison, Gibson, Stevenson, etc) as opposed to the Anglo-Saxon equivalent “-ing” (e.g. Manning, Harding, etc). The Vikings spoke Old Norse, an early North Germanic language not that dissimilar to Anglo-Saxon and roughly similar to modern Icelandic (the word viking actually means “a pirate raid” in Old Norse). Accents and pronunciations in northern England even today are heavily influenced by Old Norse, to the extent that they are largely intelligible in Iceland. Over time, Old Norse was gradually merged into the English language, and many Scandinavian terms were introduced. In actual fact, only around 150 Norse words appear in Old English manuscripts of the period, but many more became assimilated into the language and gradually began to appear in texts over the next few centuries. In all, up to 1,000 Norse words were permanently added to the English lexicon, among them, some of the most common and fundamental in the language, including skull, skin, leg, neck, freckle, sister, husband, fellow, wing, bull, score, seat, root, bloom, bag, gap, knife, dirt, kid, link, gate, sky, egg, cake, skirt, band, bank, birth, scrap, skill, thrift, window, gasp, gap, law, anger, trust, silver, clasp, call, crawl, dazzle, scream, screech, race, lift, get, give, are, take, mistake, rid, seem, want, thrust, hit, guess, kick, kill, rake, raise, smile, hug, call, cast, clip, die, flat, meek, rotten, tight, odd, rugged, ugly, ill, sly, wrong, loose, happy, awkward, weak, worse, low, both, same, together, again, until, etc. Old Norse often provided direct alternatives or synonyms for Anglo-Saxon words, both of which have been carried on (e.g. Anglo-Saxon craft and Norse skill, wish and want, dike and ditch, sick and ill, whole and hale, raise and rear, wrath and anger, hide and skin, etc). Unusually for language development, English also adopted some Norse grammatical forms, such as the pronouns they, them and their, although these words did not enter the dialects of London and southern England until as late as the 15th Century. Under the influence of the Danes, Anglo-Saxon word endings and inflections started to fall away during the time of the Danelaw, and prepositions like to, with, by, etc became more important to make meanings clear, although many inflections continued into Middle English, particularly in the south and west (the areas furthest from Viking influence). |

He is revered by many as having single-handedly saved English from the destruction of the Vikings, and by the time of his death in 899 he had raised the prestige and scope of English to a level higher than that of any other vernacular language in Europe. The West Saxon dialect of Wessex became the standard English of the day (although the other dialects continued nontheless), and for this reason the great bulk of the surviving documents from the Anglo-Saxon period are written in the dialect of Wessex. The following paragraph from Aelfrich’s 10th Century “Homily on St. Gregory the Great” gives an idea of what Old English of the time looked like (even if not how it sounded): Eft he axode, hu ðære ðeode nama wære þe hi of comon. Him wæs geandwyrd, þæt hi Angle genemnode wæron. þa cwæð he, "Rihtlice hi sind Angle gehatene, for ðan ðe hi engla wlite habbað, and swilcum gedafenað þæt hi on heofonum engla geferan beon."A few words stand out immediately as being identical to their modern equivalents (he, of, him, for, and, on) and a few more may be reasonably easily guessed (nama became the modern name, comon became come, wære became were, wæs became was). But several more have survived in altered form, including axode (asked), hu (how), rihtlice (rightly), engla (angels), habbað (have), swilcum (such), heofonum (heaven), and beon (be), and many more have disappeared completely from the language, including eft (again), ðeode (people, nation), cwæð (said, spoke), gehatene (called, named), wlite (appearance, beauty) and geferan (companions), as have special characters like þ (“thorn”) and ð (“edh” or “eth”) which served in Old English to represent the sounds now spelled with “th”.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment