PELOPONNESIAN WAR

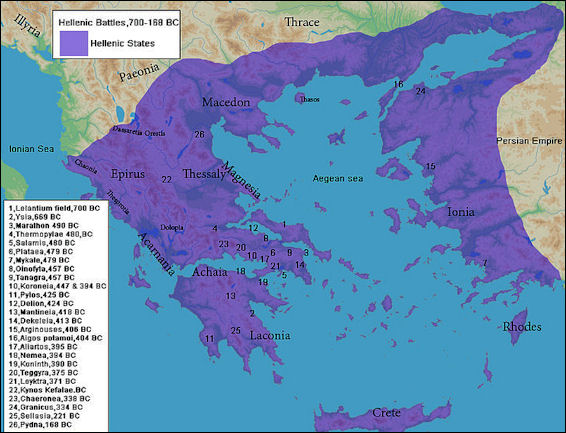

Battles of Ancient GreeceThroughout the 5th century B.C., particularly between 460 and 445 B.C., alliances led by Athens and Sparta fought one another for control of Greece. The historian and general Thucydides attributed the trouble to "greed and ambition" and wrote "practically the whole Hellenic world was convulsed." In Sparta, an An earthquake in 464 B.C. destroyed the city-state and provoked an uprising.

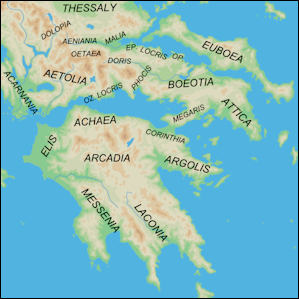

The 27-year Peloponnesian War (431 B.C. to 404 B.C.) is named after the Peloponnesian League, an alliance led by Sparta that included Corinth and Thebes, that dominated the Peloponnesian peninsula . Sparta had traditionally been stronger militarily than Athens but Athens was stronger and richer as a result of tributes pouring in through the Delian League---an alliance that stretched across the Mediterranean.

The Peloponnesian War was one of the of bloodiest and cruelest wars in ancient history. Greeks for Athens and Sparta committed horrible atrocities against one another and refused to tolerate neutrality by the other Greek city states. Children were murdered in their classrooms by mercenaries; civilians were murdered and enslaved en masse; worshippers were burned at the altar where the prayed and the dead were left to rot in the battlefields.

The Peloponnesian War has been compared to the Cold War, with some history saying it serves as a parable to what might have happened if things got out of hand between the United States (Athens) and the Soviet Union (Sparta). In February 1947, after World War II and as the Cold War was getting started, U.S. President Truman's said during a speech at Princeton University, “I doubt seriously whether a man can think with full wisdom and with deep convictions regarding some of the basic international issues today who has not at least reviewed in his mind the period of the Peloponnesian War and the Fall of Athens."

Books and Experts: History of Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, translated by Rex Warden (Penguin, 1972); Peloponnesian War , a four-volume study on the war, by Donald Kagan (2004, Viking). Kagan is a professor of classics and history at Yale known for conservative political views. Victor Davis Hanson is another expert of the Peloponnesian War at the California State University, Fresno. Dick Cheney described him as his favorite historian and the person who summed up his own philosophy best (One of the lessons of the Peloponnesian War Hanson wrote was that “resolute action” brings “lasting peace”).

Greece on the Eve of the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War was the culmination of 40 years of simmering tensions between the era's two great superpowers: free-wheeling, democratic Athens and Sparta, a militaristic oligarchy. Angry about trade restrictions and imperialism, and contemptuous of Athenian permissiveness and lack of discipline, Sparta declared war on Athens in 431 B.C. The war lasted for 27 years, drained both sides of resources, morale and energy.

The Peloponnesian War was the culmination of 40 years of simmering tensions between the era's two great superpowers: free-wheeling, democratic Athens and Sparta, a militaristic oligarchy. Angry about trade restrictions and imperialism, and contemptuous of Athenian permissiveness and lack of discipline, Sparta declared war on Athens in 431 B.C. The war lasted for 27 years, drained both sides of resources, morale and energy.

The Peloponnesian League was fed up with Athens, its political subversion and commercial dominance and it viewed Athens as a threat. Some historians argue that the Peloponnesian War was the result of a break down of a balance of power between two adversaries---Athens and Sparta---and the swift, expansion of one side---Athens.

Both sides championed the war as one of liberation with each side claiming too free a bullied ally. The war began with a relatively small dispute over Corinth, a Spartan ally, and some minor fighting in a town near Athens and escalated into a conflict that years, involved numerous states, and ended with the demise of Athens and the abolition of its democratic institutions.

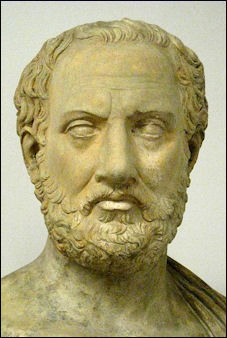

Thucydides and the Peloponnesian War

Thucydides (471?-400? B.C.) wrote extensively about events in Greece and told the story of the draining, disastrous 30-year Peloponnesian War that destroyed Athens when it was in its prime in History of the Peloponnesian War . Little known about his life other than that he was an soldier and an officer. One of the few times he talks about himself is when he mentions he survived the plague. [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker, January 12, 2004]

Thucydides (471?-400? B.C.) wrote extensively about events in Greece and told the story of the draining, disastrous 30-year Peloponnesian War that destroyed Athens when it was in its prime in History of the Peloponnesian War . Little known about his life other than that he was an soldier and an officer. One of the few times he talks about himself is when he mentions he survived the plague. [Source: Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker, January 12, 2004]

Tracy Lee Simmons wrote in the Washington Post: “One of the most eminently, and now, predictably, quotable figures of the classical world, Thucydides assuredly deserves his press. Few so well understood the machinations of he human heart and mind when facing the extremities of the human predicament---plague, betrayal, defeat, and the abject humiliation of war---and fewer still could distill the hard-won wisdom of experience into tight, shimmering phrases and radiant lapidary passages."

Thucydides was a participant in the events he described. He caught the plague he detailed with such precision. He was also far from a distant observer of the Peloponnesian War: he was a general high in the Athenian command early in the war who was forced into exile after he failed to prevent the Spartans from capturing the northern city of Amphipolis in 422. He wrote his account years later in part to defend his actions and in the end puts the blame on the demise of Athens on democracy and its demagogue politicians while arguing it was enlightened military that almost saved the day.

Book: Thucydides, The Reinvention of History by Donald Kagan (Viking, 2009). Kagan is a professor of classics and history at Yale.

Thucydides's History of the Peloponnesian War is the only extant eyewitness account of the first twenty year of the war. He said he began taking notes “at the very outbreak” of the conflict because he had hunch it would be---a great war and more worthy writing about than any of those which had taken place in the past." His accounts end in mid sentence during the description of a naval battle in 411 but we can tell from other references in his work that he was around to see the war end in 404 B.C.

Fighting in the Peloponnesian War

After a diplomatic crisis involving the Corinth ties between Athens and Sparta fell part. Fighting began with a sneak attack in 431 B.C. on the small Athenian protectorate called Plataea, a move widely viewed as an egregious violation of the Greek etiquette of warfare and set the tone for things to come. Yale historian Donald Kagan wrote the hostilities set off cycle of cruelty and reprisals that ended in a “collapse of in the habits, institutions, beliefs and restraints that are the foundations of civilized life."

After a diplomatic crisis involving the Corinth ties between Athens and Sparta fell part. Fighting began with a sneak attack in 431 B.C. on the small Athenian protectorate called Plataea, a move widely viewed as an egregious violation of the Greek etiquette of warfare and set the tone for things to come. Yale historian Donald Kagan wrote the hostilities set off cycle of cruelty and reprisals that ended in a “collapse of in the habits, institutions, beliefs and restraints that are the foundations of civilized life."

Athens won a series of important battles at the beginning of the war. Athens clearly had the advantage at the outset because Sparta had no navy. To counter Sparta's dominance on land, the Athens adopted the foolishly passive defensive strategy of remaining within their Long Wall---which surrounded Athens and its port in Piraeus 10 kilometers away---and putting up with the Spartans burning their crops, by relying on their navy to ship in food supplies from its Mediterranean allies.

Things began going badly for the Athenians when the plague struck in 429 and killed a quarter of the city's population (See Below). The political scene in Athens then began to be dominated by demagogues like Cleon who roused the masses with crude rhetoric that Aristophanes likened to the squeals of a scaled pig and urged them to pursue a more aggressive strategy. Under Cleon the war became a series of surprise victors such as the capture of a tenth of the Spartan army at Sphacteri in 425 B.C. and the stinging loses such defeat at Delium in 424 B.C. In 427 B.C. Cleon proposed killing all the men and enslaving all the women in the city of Mytilnes on the island of Lesbos, The Athenian assembly approved the measure only to have a change of heart and rescind it the next day.

The Athenians would eventually go on to carry out a number of atrocities. In 416 B.C., under the Alcibiades, they invaded the island of Melos, killing all the men and enslaving everyone else for the crime of being neutral. For many historians this event was the watershed of Athens's moral decline. The Spartans also used underhanded tactics. After Athens attacked the Spartan port of Gytheion and set fire to Spartan ships, Spartan soldiers retaliated by disguising themselves as visiting athletes and retook the port.

The tide turned after Sparta received aid from its old enemy Persia. By thus time Sparta's tactic of burning crops was really beginning to take its tool. Violent internal strife, economic problems and a succession of oppressive regime was ripping Sparta apart from the inside. Sparta's alliance with Persian gave it an economic crutch enabling it to weather its own troubles and build an army and navy at a critical moment.

Battle of Syracuse and the Fall of Athens

The decisive battle occurred on Sicily at Syracuse, an ally of Sparta. The event occupies two full books of Thucydides account of the war, The flamboyant general Alcibades persuaded the Athenian assembly to send a huge armada to attack Syracuse. In the Battle of Syracuse the underdog Sicilians routed the Athenians after they sailed into their harbor and were trapped. The Athenian armada was decimated at the Aegispotami in the Hellespont in 405 B.C. .

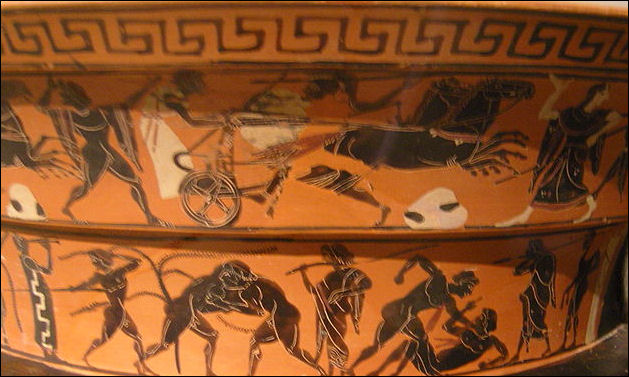

Battle scenes and ships

During the disastrous Sicilian expeditions Athens needed the help of the islanders on Melos, who the Athenians had just ruthlessly slaughtered. The total defeat of the Athenian fulfilled a prediction by the Melians. “We know that in war fortune sometimes makes odds more level than could be expected." Thucydides wrote, “They now suffered very nearly what they had inflicted, They had come to enslave others, and were departing in fear of being enslaved themselves."

After the defeat in Sicily, Sparta counterattacked with soldiers in blood-red cloaks. The Spartans cut off Athens grain supply from Thrace and the Black Sea and laid siege to Athens: people starved, more fields were burned.

Athens surrendered to Sparta in April 404 B.C. The Long Walls that surrounded Athens were torn down by the Spartans to music of flutes. Sparta installed despotic rulers but mercifully allowed Athens' people to live. Captured Athenian soldiers were put to work as slaves in Syracuse's stone quarries.

After the Peloponnesian War

The decline of Greek civilization and the end of the Golden Age of Athens began in 404 B.C. with Sparta's victory over Athens in the Great Peloponnesian War. Although democracy was reestablished in Athens in the 4th century B.C. and Plato founded of the Academy in 387 B.C. and Aristotle founding the Lyceum in 335 B.C., the war left Greece bitterly divided and open to conquest from Macedonia.

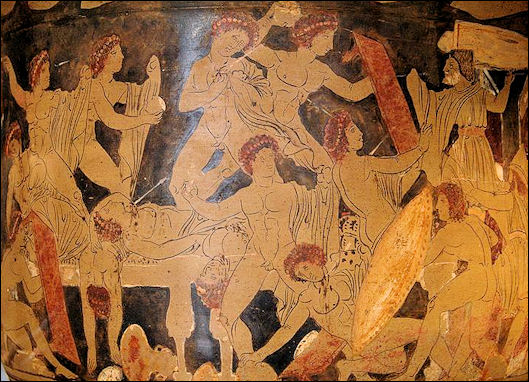

Mnesterophonia

After the Peloponnesian Wars, Greek culture declined: ambition replaced honor, oratory skill became a method of furthering one's career and attaining power, democratic institutions were undermined by corruption and citizens demanded “rights, not duties, and pleasure instead of work."

Sparta remained the supreme power in Greece for about 30 years. Non-Spartan Greeks chafed under Spartan rule. There were rebellions and unrest and progressively fewer Spartan warrior to carry on the traditions. Finally when only a few hundred Spartan citizen-soldier remained the Thebans under Epaminodas defeated Sparta. Later it like the rest of Greece came under the control of Alexander the Great.

Plague in Athens in 430 B.C.

The After the Peloponnese War began, in 430 B.C., Athens was devastated by a mysterious plague that ripped through the city-state's military, killed Pericles and affected the course of the Peloponnese war.

No one is sure exactly what disease the plague of Athens was. Some believe it was the Ebola virus, or perhaps the bubonic plague. It had same symptoms of typhus fever but otherwise was not like any known disease.

The best account of the plague was written by Thucydides. He wrote: "The disease began, it is said, in Ethiopia beyond Egypt, and then...it suddenly fell upon the city of Athens...Athenians suffered...hardship owing to the crowding into the city of the people from the country districts...Bodies of dying men upon another, and half dead rolled about in the streets and , in their longing for water, near all the fountains. The temples too , in which they had quartered themselves, were full of corpses of those who died in them."

Symptoms of the Plague in Athens in 430 B.C.

Thucydides manuscriptThucydides wrote: "Suddenly while in good health, men were seized first with intense heat of the head, and redness in the mouth, both the throat and the tongue, immediately became blood-red and exhaled an unnatural fetid breath."

"In the next stage , sneezing and hoarsnesss came on , an in a short time the disorder descended to the chest, attended by severe coughing. And when it settled in the stomach that was upset, and vomits of bile of every kind named by physicians ensued, there also attended by great distress; and in most cases ineffectual retching followed by violent convulsions...Externally the body was very hot to the touch ; it was not pale but reddish, livid, and breaking out in small blisters and ulcers."

"Internally it was consumed by such heat that the patients could not bear to have on them the lightest covering...and would have liked to throw themselves into cold water...When the patients died, as most of them did on the seventh to ninth day from internal heat, they still had some strength left."

Among the illnesses that have been suggested or proposed are dysentery, smallpox, measles, influenza, anthrax, typhus, bubonic plague and a host of other illnesses including an Ebola-like virus. Most of the diseases don't pass the test for one reason or another.

End and Legacy of Classical Greece

Weakened by feuds between rival city states and threat from Carthage and Rome, the Greek colonies eventually were conquered by the Romans around 210 B.C., but Greek cultures, customs and language lasted for centuries more. When Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, most people in Naples still spoke Greek as their first language.

In 146 B.C. the Romans destroyed Carthage and Corinth, the home of the last Greek league of cities that had tried to resist Roman expansion. Under the command of Roman consul Lucius Mummius Corinthian men were slaughtered, women and children were sold into slavery, art was shipped back to Rome and Corinth was turned into a ghost town.

Ancient Greece is still very close to use today. Many of are buildings are constructed to look like Greek temples, our coins have changed little in design since Greek coins, our comedies are based as many of the same kind of jokes used in Greek plays and some of our greatest sporting events are modeled on ancient Greek games. [Source: "History of Art" by H.W. Janson, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J."

People on the isolated village of Ólimbos speak a Greek dialect that is so old some of the words date back to Homer's time. Their musical instruments include goatskin bagpipes and the three stringed lyre. The tools they use to cultivate wheat and barley are the same as those used by the Byzantines.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Most of the information about Greco-Roman science, geography, medicine, time, sculpture and drama was taken from "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. Most of the information about Greek everyday life was taken from a book entitled "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum [||]

No comments:

Post a Comment