Introduction to the Romans

1.1 – Introduction

Rome was founded in the mid-eighth century BCE by eight tribes who settled in Etruria and on the famous Seven Hills.

1.1.1 – Foundation Myths

The Romans relied on two sets of myths to explain their origins: the first story tells the tale of Romulus and Remus, while the second tells the story of Aeneas and the Trojans, who survived the sack of Troy by the Greeks. Oddly, both stories relate the founding of Rome and the origins of its people to brutal murders.

Romulus killed his twin brother, Remus, in a fit of rage, and Aeneas slaughtered his rival Turnus in combat. Roman historians used these mythical episodes as the reason for Rome’s own bloody history and periods of civil war. While foundation myths are the most common vehicle through which we learn about the origins of Rome and the Roman people, the actual history is often overlooked.

1.1.2 – The Historical Record

Archaeological evidence shows that the area that eventually became Rome has been inhabited continuously for the past 14,000 years. The historical record provides evidence of habitation on and fortification of the Palatine Hill during the eighth century BCE, which supports the date of April 21, 753 BCE, as the date that ancient historians applied to the founding of Rome in association with a festival to Pales, the goddess of shepherds. Given the importance of agriculture to pre-Roman tribes, as well as most ancestors of civilization , it is logical that the Romans would link the celebration of their founding as a city to an agrarian goddess.

Romulus, whose name is believed to be the namesake of Rome, is credited for Rome’s founding. He is also credited with establishing the period of monarchical rule. Six kings ruled after him until 509 BCE, when the people rebelled against the last king, Tarquinius Superbus, and established the Republic. Throughout its history, the people—including plebeians , patricians , and senators—were wary of giving one person too much power and feared the tyranny of a king.

1.1.3 – Pre-Roman Tribes

The villages that would eventually merge to become Rome were descended from the Italic tribes. The Italic tribes spread throughout the present-day countries of Italy and Sicily. Archaeological evidence and ancient writings provide very little information on how—or whether—pre-Roman tribes across the Italian peninsula interacted.

What is known is that they all belonged to the Indo-European linguistic family, which gave rise to the Romance (Latin-derived) and Germanic languages. What follows is a brief history of two of the eight main tribes that contributed to the founding of Rome: the Latins and the Sabines.

1.1.4 – The Latins

Cinerary urn: This Villanovan urn likely replicates the form that pre-Roman Latin huts assumed before the mid-seventh century BCE.

The Latins inhabited the Alban Hills since the second millennium BCE. According to archaeological remains, the Latins were primarily farmers and pastoralists . Approximately at the end of the first millennium BCE, they moved into the valleys and along the Tiber River, which provided better land for agriculture.

Although divided from an early stage into communities that mutated into several independent, and often warring, city-states , the Latins and their neighbors maintained close culturo-religious relations until they were definitively united politically under Rome. These included common festivals and religious sanctuaries.

The Latins appear to have become culturally differentiated from the surrounding Italic tribes from about 1000 BCE onward. From this time, the Latins’ material culture shares more in common with the Iron Age Villanovan culture found in Etruria and the Po valley than with their former Osco-Umbrian neighbors.

The Latins thus shared a similar material culture as the Etruscans. However, archaeologists have discerned among the Latins a variant of Villanovan, dubbed the Latial culture.

The most distinctive feature of Latial culture were cinerary urns in the shape of huts . They represent the typical, single-room abodes of the area’s peasants, which were made from simple, readily available materials: wattle-and-daub walls and straw roofs supported by wooden posts. The huts remained the main form of Latin housing until the mid-seventh century BCE.

1.1.5 – The Sabines

Pre-Roman tribes: Map showing the locations of the tribes who settled Rome.

The Sabines originally inhabited the Apennines and eventually relocated to Latium before the founding of Rome. The Sabines divided into two populations just after the founding of Rome. The division, however it came about, is not legendary.

The population closer to Rome transplanted itself to the new city and united with the pre-existing citizenry to start a new heritage that descended from the Sabines but was also Latinized. The second population remained a mountain tribal state, finally fighting against Rome for its independence along with all the other Italic tribes. After losing, it became assimilated into the Roman Republic.

There is little record of the Sabine language. However, there are some glosses by ancient commentators, and one or two inscriptions have been tentatively identified as Sabine. There are also personal names in use on Latin inscriptions from the Sabine territories, but these are given in Latin form. The existing scholarship classifies Sabine as a member of the Umbrian group of Italic languages and identifies approximately 100 words that are either likely Sabine or that possess Sabine origin.

1.1.6 – The Seven Hills

Before Rome was founded as a city, its people existed in separate settlements atop its famous Seven Hills:

- The Aventine Hill

- The Caelian Hill

- The Capitoline Hill

- The Esquiline Hill

- The Palatine Hill

- The Quirinal Hill

- The Viminal Hill

Over time, each tribe either united with or was absorbed into the Roman culture.

1.1.7 – The Quirinal Hill

Recent studies suggest that the Quirinal Hill was very important to the ancient Romans and their immediate ancestors. It was here that the Sabines originally resided. Its three peaks were united with the three peaks of the Esquiline, as well as villages on the Caelian Hill and Suburra.

Tombs from the eighth to the seventh century BCE that confirm a likely presence of a Sabine settlement area were discovered on the Quirinal Hill. Some authors consider it possible that the cult of the Capitoline Triad (Jove, Minerva, Juno) could have been celebrated here well before it became associated with the Capitoline Hill. The sanctuary of Flora, an Osco-Sabine goddess, was also at this location. Titus Livius (better known as Livy) writes that the Quirinal Hill, along with the Viminal Hill, became part of Rome in the sixth century BCE.

1.1.8 – The Palatine Hill

The Seven Hills of Rome: A schematic map of Rome showing the Seven Hills.

According to Livy, the Palatine Hill, located at the center of the ancient city, became the home of the original Romans after the Sabines and the Albans moved into the Roman lowlands. Due to its historical and legendary significance, the Palatine Hill became the home of many Roman elites during the Republic and emperors during the Empire.

It was also the site of a temple to Apollo built by Emperor Augustus and the pastoral (and possibly pre-Roman) festival of Lupercalia, which was observed on February 13 through 15 to avert evil spirits, purify the city, and release health and fertility.

Festivals for the Septimontium (meaning of the Seven Hills) on December 11 were previously considered to be related to the foundation of Rome. However, because April 21 is the agreed-upon date of the city’s founding, it has recently been argued that Septimontium celebrated the first federations among the Seven Hills. A similar federation was celebrated by the Latins at Cave or Monte Cavo.

1.2 – Roman Society

Ancient Roman society was based on class-based and political structures, as well as by religious practices.

1.2.1 – Social Structure

Life in ancient Rome centered around the capital city with its fora, temples, theaters, baths, gymnasia, brothels, and other forms of culture and entertainment. Private housing ranged from elegant urban palaces and country villas for the social elites to crowded insulae (apartment buildings) for the majority of the population.

The large urban population required an endless supply of food, which was a complex logistical task. Area farms provided produce, while animal-derived products were considered luxuries. The aqueducts brought water to urban centers, and wine and oil were imported from Hispania (Spain and Portugal), Gaul (France and Belgium), and Africa.

Highly efficient technology allowed for frequent commerce among the provinces. While the population within the city of Rome might have exceeded one million, most Romans lived in rural areas, each with an average population of 10,000 inhabitants.

Roman society consisted of patricians , equites (equestrians, or knights), plebeians , and slaves. All categories except slaves enjoyed the status of citizenship.

In the beginning of the Roman republic, plebeians could neither intermarry with patricians or hold elite status, but this changed by the Late Republic, when the plebeian-born Octavian rose to elite status and eventually became the first emperor. Over time, legislation was passed to protect the lives and health of slaves.

Although many prostitutes were slaves, for instance, the bill of sale for some slaves stipulated that they could not be used for commercial prostitution. Slaves could become freedmen—and thus citizens—if their owners freed them or if they purchased their freedom by paying their owners. Free-born women were considered citizens, although they could neither vote nor hold political office.

1.2.2 – Pater Familias

Roman family: Relief of a Roman family with the child in the middle, the father on the left, and the mother on the right.

Within the household, the pater familias was the seat of authority, possessing power over his wife, the other women who bore his sons, his children, his nephews, his slaves, and the freedmen to whom he granted freedom. His power extended to the point of disposing of his dependents and their good, as well as having them put to death if he chose.

In private and public life, Romans were guided by the mos maiorum, an unwritten code from which the ancient Romans derived their social norms that affected all aspects of life in ancient Rome.

1.2.3 – Government

The Roman Senate: A nineteenth-century fresco in the Palazzo Madama in Rome, depicting a sitting of the Roman Senate in which the senator Cicero attacks the senator Catiline.

Over the course of its history, Rome existed as a kingdom (hereditary monarchy), a republic (in which leaders were elected), and an empire (a kingdom encompassing a wider swath of territory). From the establishment of the city in 753 BCE to the fall of the empire in 476 CE, the Senate was a fixture in the political culture of Rome, although the power it exerted did not remain constant.

During the days of the kingdom, it was little more than an advisory council to the king. Over the course of the Republic, the Senate reached the height of its power, with old-age becoming a symbol of prestige, as only elders could serve as senators. However the late Republic witnessed the beginning of its decline. After Augustus ended the Republic to form the Empire, the Senate lost much of its power, and with the reforms of Diocletian in the third century CE, it became irrelevant.

As Rome grew as a global power, its government was subdivided into colonial and municipal levels. Colonies were modeled closely on the Roman constitution, with roles being defined for magistrates, council, and assemblies. Colonists enjoyed full Roman citizenship and were thus extensions of Rome itself.

The second most prestigious class of cities was the municipium (a town or city). Municipia were originally communities of non-citizens among Rome’s Italic allies. Later,Roman citizenship was awarded to all Italy, with the result that a municipium was effectively now a community of citizens. The category was also used in the provinces to describe cities that used Roman law but were not colonies.

1.2.4 – Religion

The Roman people considered themselves to be very religious. Religious beliefs and practices helped establish stability and social order among the Romans during the reign of Romulus and the period of the legendary kings. Some of the highest religious offices, such as the Pontifex Maximus , the head of the state’s religion—which eventually became one of the titles of the emperor—were sought-after political positions.

Women who became Vestal Virgins served the goddess of the hearth, Vesta, and received a high degree of autonomy within the state, including rights that other women would never receive.

The Roman pantheon corresponded to the Etruscan and Greek deities . Jupiter was considered the most powerful and important of all the Gods.

In nearly every Roman city, a central temple known as the Capitolia that was dedicated to the supreme triad of deities: Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva (Zeus, Hera, and Athena). Small household gods, known as Lares, were also popular.

Lararium: A fresco and stucco lararium from the House of the Vettii.

Each family claimed their own set of personal gods and laraium, or shines to the Lares, are found not only in houses but also at street corners, on roads, or for a city neighborhood.

Roman religious practice often centered around prayers, vows, oaths, and sacrifice . Many Romans looked to the gods for protection and would complete a promise sacrifice or offering as thanks when their wishes were fulfilled. The Romans were not exclusive in their religious practices and easily participated in numerous rituals for different gods. Furthermore, the Romans readily absorbed foreign gods and cults into their pantheon.

Capitoline Triad: Juno, Jupiter, and Minerva made up the Capitoline Triad. They often shared a temple, known as the Capitolia, in the center of a Roman city. This photo is taken in the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia, Palestrina, Italy.

With the rise of imperial rule, the emperors were considered gods, and temples were built to many emperors upon their death. Their family members could also be deified, and the household gods of the emperor’s family were also incorporated into Roman worship.

2 – The Republic

2.1 – Roman Sculpture under the Republic

During the Roman Republic, members of all social classes used a variety of sculptural techniques to promote their distinguished social statuses.

2.1.1 – Introdution

Early Roman art was influenced by the art of Greece and that of the neighboring Etruscans, themselves greatly influenced by their Greek trading partners. As the expanding Roman Republic began to conquer Greek territory, its official sculpture became largely an extension of the Hellenistic style , with its departure from the idealized body and flair for the dramatic. This is partly due to the large number of Greek sculptors working within Roman territory.

However, Roman sculpture during the Republic departed from the Greek traditions in several ways.

- It was the first to feature a new technique called continuous narration.

- Commoners, including freedmen, could commission public art and use it to cast their professions in a positive light.

- Portraiture throughout the Republic celebrated old age with its verism .

- In the closing decades of the Republic, Julius Caesar counteracted traditional propriety by becoming the first living person to place his own portrait on a coin.

In the examples that follow, the patrons use these techniques to promote their status in society.

2.1.2 – The Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus

Despite its most common title, the Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus (late second century BCE) was more likely a base intended to support cult statues in the cella of a Temple of Neptune (Poseidon) located in Rome on the Field of Mars. The frieze is the second oldest Roman bas- relief currently known.

Domitius Ahenobarbus, a naval general, likely commissioned the altar and the temple in gratitude of a naval victory between 129 and 128 BCE. The reliefs combine mythology and contemporary civic life.

One panel of the altar depicts the census, a uniquely Roman event of contemporary civic life. It is one of the earliest reliefs sculpted in continuous narration, in which the viewer reads from left to right the recording of the census, the purification of the army before the altar of Mars, and the levy of the soldiers.

Altar of Domitius Ahenobarb: This panel of the altar depicts the census, a uniquely Roman event of contemporary civic life.

The other three panels depict the mythological wedding of Neptune and Amphitrite. At the center of his scene, Neptune and Amphitrite are seated in a chariot drawn by two Tritons (messengers of the sea) who dance to music. They are accompanied by a multitude of fantastic creatures, Tritons, and Nereides (sea nymphs) who form a retinue for the wedding couple, which, like the census scene, can be read from left to right.

Altar of Domitius Ahenobarb: The other three panels of the altar depict the mythological wedding of Neptune and Amphitrite.

At the left, a Nereid riding on a sea-bull carries a present. Next, Amphitrite’s mother Doris advances towards the couple, mounted on a hippocampus (literally, a sea horse) and holding wedding torches in each hand to light the procession’s way. Eros hovers behind her. Behind the wedding couple, a Nereid riding a hippocampus carries another present.

2.1.3 – Tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces the Baker

The Tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces the Baker: The frieze represents various stages in the baking of bread in continuous narration.

The patronage of public sculpture was not limited to the ruling classes during the Republic. The tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces the Baker (c. 50–20 BCE) is one of the largest and best-preserved freedman funerary monuments in Rome. Its sculpted frieze is a classic example of the plebeian style in Roman sculpture.

The deceased built the tomb for himself and perhaps his wife Atistia in the final decades of the Republic. While the tomb’s inscription lacks an L to denote the status of a freedman, the tripartite name of the deceased follows the pattern of names given to and adopted by former slaves.

The tomb, approximately 33 feet tall, commemorates the deceased and his profession. It three main components are a frieze at the top and the cylindrical niches (probably symbolic of a kneading machine or grain measuring vessels) below it.

The surviving text of the inscription translates as “This is the monument of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, baker, contractor, public servant.” The frieze represents various stages in the baking of bread in continuous narration.

Although time-worn, the naturalistic depiction of human and animal bodies in a variety of poses is still evident. This record of each stage in a mundane process demonstrates the sense of pride the deceased must have had in his profession. Because the wearing of togas was not conducive to manual labor, the simple clothing on the figures marks them as plebeians, or commoners.

2.1.4 – Portraiture

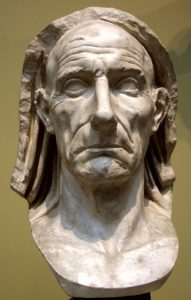

Roman portraiture during the Republic is identified by its considerable realism, known as veristic portraiture. Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics. The style originated from Hellenistic Greece; however, its use in the Roman Republic is due to Roman values , customs, and political life.

As with other forms of Roman art, portraiture borrowed certain details from Greek art but adapted these to their own needs. Veristic images often show their male subjects with receding hairlines, deep winkles, and even with warts. While the faces of the portraits often display incredible detail and likeness, the subjects’ bodies are idealized and do not correspond to the age shown in the face.

[LEFT]: Portrait of a Roman General: When created as full-length sculptures, the veristic portrait busts appear to have been paired with idealized (mass-produced?) bodies that create a sense of disunity.

[LEFT]: Portrait of a Roman General: When created as full-length sculptures, the veristic portrait busts appear to have been paired with idealized (mass-produced?) bodies that create a sense of disunity.

[RIGHT]: Bust of an old man: Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics, such as the wrinkles on this man’s face.

The popularity and usefulness of verism appears to derive from the need to have a recognizable image. Veristic portrait busts provided a means of reminding people of distinguished ancestors or of displaying one’s power, wisdom, experience, and authority. Statues were often erected of generals and elected officials in public forums—and a veristic image ensured that a passerby would recognize the person when they actually saw them.

[RIGHT]: Bust of an old man: Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics, such as the wrinkles on this man’s face.

2.1.5 – The Late Republic

Marble bust of Pompey the G

reat: Portraits of Pompey combine a degree of verism with an idealized hairstyle reminiscent of Alexander the Great.

The use of veristic portraiture began to diminish in the first century BCE. During this time, civil wars threatened the empire, and individual men began to gain more power. The portraits of Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar, two political rivals who were also the most powerful generals in the Republic, began to change the style of the portraits and their use.

The portraits of Pompey are not fully idealized, nor were they created in the same veristic style of Republican senators. Pompey borrowed a specific parting and curl of his hair from Alexander the Great . This similarity served to link Pompey visually with the likeness of Alexander and to remind people that he possessed similar characteristics and qualities.

Julius Caesar portrait: A portrait of Julius Caesar on a denarius. On the reverse side stands Venus Victix holding a winged Victory.

The portraits of Julius Caesar are more veristic than those of Pompey. Despite staying closer to stylistic convention, Caesar was the first man to mint coins with his own likeness printed on them. In the decades prior to this, it had become increasingly common to place an illustrious ancestor on a coin, but putting a living person—especially oneself—on a coin departed from Roman propriety. By circulating coins issued with his image, Caesar directly showed the people that they were indebted to him for their own prosperity and therefore should support his political pursuits.

reat: Portraits of Pompey combine a degree of verism with an idealized hairstyle reminiscent of Alexander the Great.

The use of veristic portraiture began to diminish in the first century BCE. During this time, civil wars threatened the empire, and individual men began to gain more power. The portraits of Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar, two political rivals who were also the most powerful generals in the Republic, began to change the style of the portraits and their use.

The portraits of Pompey are not fully idealized, nor were they created in the same veristic style of Republican senators. Pompey borrowed a specific parting and curl of his hair from Alexander the Great . This similarity served to link Pompey visually with the likeness of Alexander and to remind people that he possessed similar characteristics and qualities.

Julius Caesar portrait: A portrait of Julius Caesar on a denarius. On the reverse side stands Venus Victix holding a winged Victory.

The portraits of Julius Caesar are more veristic than those of Pompey. Despite staying closer to stylistic convention, Caesar was the first man to mint coins with his own likeness printed on them. In the decades prior to this, it had become increasingly common to place an illustrious ancestor on a coin, but putting a living person—especially oneself—on a coin departed from Roman propriety. By circulating coins issued with his image, Caesar directly showed the people that they were indebted to him for their own prosperity and therefore should support his political pursuits.

2.1.6 – Death Masks

The creation and use of death masks demonstrate Romans’ veneration of their ancestors. These masks were created from molds taken of a person at the time of his or her death. Made of wax, bronze , marble, and terra cotta , death masks were kept by families and displayed in the atrium of their homes.

Visitors and clients who entered the home would have been reminded of the family’s ancestry and the honorable qualities of their ancestors. Such displays served to bolster the reputation and credibility of the family.

Death masks were also worn and paraded through the streets during funeral procession. Again, this served not only a memorial for the dead, but also to link the living members of a family to their illustrious ancestors in the eyes of the spectator.

2.2 – Roman Architecture under the Republic

Roman architecture relies heavily on the use of concrete and the arch to create unique interior spaces and architectural forms.

2.2.1 – Introduction

Greek and Roman column orders: From top to bottom: Doric and Tuscan, Ionic and Roman Ionic (scrolls on all four corners), Corinthian and Composite.

Roman architecture began as an imitation of Classical Greek architecture but eventually evolved into a new style. Unfortunately, almost no early Republican buildings remain intact. The earliest substantial remains date to approximately 100 BCE.

Innovations such as improvements to the round arch and barrel vault , as well as the inventions of concrete and the true hemispherical dome, allowed Roman architecture to become more versatile than its Greek predecessors. While the Romans were reluctant to abandon classical motifs , they modified their temple designs by abandoning pedimental sculptures, altering the traditional Greek peripteral colonnades , and opting for central exterior stairways.

Likewise, although Roman architects did not abandon traditional column orders, they did modify them with the Tuscan, Roman Ionic, and Composite orders. This diagram shows the Greek orders on the left and their Roman modifications on the right.

2.2.2 – Roman Temples

Most Roman temples derived from Etruscan prototypes. Like Etruscan temples, Roman temples are frontal with stairs that lead up to a podium, and a deep portico filled with columns. They are also usually rectilinear , and the interiors consist of at least one cella that contained a cult statue.

If multiple gods were worshiped in one temple, each god would have its own cella and cult image. For example, Capitolia—the temples dedicated to the Capitoline Triad—would always be built with three cellae, one for each god of the triad: Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.

The Temple of Portunus : A typical Roman Republican temple. Rome, c. 75 BCE.

Roman temples were typically made of brick and concrete and then faced in either marble or stucco. Engaged columns (columns that protrude from walls like reliefs) adorn the exteriors of the temples. This creates an effect of columns completely surrounding a cella, an effect known as psuedoperipteral . The altar, used for sacrifices and offerings , always stood outside in front of the temple.

Temple of Hercules Victor: A Roman modification of a Greek tholos. Rome, from the late second century BCE.

While most Roman temples followed this typical plan, some were dramatically different. At times, the Romans erected round temples that imitated the Greek tholos . Examples can be found in the Temple of Hercules Victor (late second century BCE), in the Forum Boarium in Rome . The temple consists a circular cella within a concentric ring of 20 Corinthian columns. Like its Etruscan predecessors, the temple rests on a tufa foundation. Its original roof and architrave are now lost.

2.2.3 – Concrete

The Romans perfected the recipe for concrete during the third century BCE by mixing together water, lime, and pozzolana , volcanic ash mined from the countryside surrounding Mt. Vesuvius. Concrete became the primary building material for the Romans, and it is largely the reason that they were such successful builders.

Most Roman buildings were built with concrete and brick that was then covered in façade of stucco, expensive stone, or marble. Concrete was a cheaper and lighter material than most other stones used for construction. This helped the Romans build structures that were taller, more complicated, and quicker to build than any previous ones.

Wall of a tomb on the Via Appia, Rome: The ruins show the internal core of the building, made in Roman concrete.

Once dried, concrete was also extremely strong, yet flexible enough to remain standing during moderate seismic activity. The Romans were even able to use concrete underwater, allowing them build harbors and breakers for their ports. The ruins of a tomb on the Via Appia (the most famous thoroughfare through ancient Rome) expose the stones and aggregate that the Romans used to mix concrete.

2.2.4 – Arches, Vaults, and Domes

The Romans effectively combined concrete and the structural shape of the arch. These two elements became the foundations for most Roman structures. Arches can bear immense weight, as they are designed to redistribute weight from the top, to its sides, and down into the ground . While the Romans did not invent the arch, they were the first culture to manipulate it and rely on its shape.

An arch is a pure compression form . It can span a large area by resolving forces into compressive stresses (pushing downward) that, in turn, eliminate tensile stresses (pushing outward). As the forces in the arch are carried to the ground, the arch will push outward at the base (called thrust). As the height of the arch decreases, the outward thrust increases. In order to maintain arch action and prevent the arch from collapsing, the thrust needs to be restrained, either with internal ties or external bracing, such as abutments (labeled 8 on the diagram below).

Schematic illustration of an arch: This diagram illustrates the structural support of an arch extended into a barrel vault. The dotted line extending downward from the keystone (1) shows the strength of the arch directing compressive stresses (represented by the downward-pointing arrows outside the arch) safely to the ground. Meanwhile, tensile stress (represented by the horizontal and diagonal-facing arrows) is contained by the surrounding wall.

The arch is a shape that can be manipulated into a variety of forms that create unique architectural spaces. Multiple arches can be used together to create a vault. The simplest type is known as a barrel vault.

Barrel vaults consist of a line of arches in a row that create the shape of a tunnel. When two barrel vaults intersect at right angles, they create a groin vault . These are easily identified by the x-shape they create in the ceiling of the vault. Furthermore, because of the direction, the thrust is concentrated along this x-shape, so only the corners of a groin vault need to be grounded. This allows an architect or engineer to manipulate the space below the groin vault in a variety of ways.

Temple of Echo at Baiae: The dome on Temple of Echo at Baiae creates the building’s remarkable acoustic properties.

Arches and vaults can be stacked and intersected with each other in a multitude of ways. One of the most important forms that they can create is the dome. This is essentially an arch that is rotated around a single point to create a large hemispherical vault. The largest dome constructed during the Republic was on the Temple of Echo at Baiae, named for its remarkable acoustic properties.

Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia (scale model): Concrete was used as the primary building material and barrel vaults provide structural support, both as a terracing method for the hill and in creating interesting architectural spaces for the sanctuary.

Arches and concrete are found in many iconic Roman structures. The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia (c. 120 BCE) at Palestrina, Italy is a massive temple structure built into the hillside in a series of terraces, exedras , and porticoes. Concrete was used as the primary building material and barrel vaults provide structural support, both as a terracing method for the hill and in creating interesting architectural spaces for the sanctuary.

Aqua Marcia: These are some ruins from the aquaduct near Tivoli, Italy, c. 144–140 BCE.

Roman aqueducts are another iconic use of the arch. The arches that make up an aqueduct provided support without requiring the amount of building material necessary for arches supported by solid walls. The Aqua Marcia (144–140 BCE) was the longest of the eleven aqueducts that served the city of Rome during the Republic. It supplied water to the Viminal Hill in the north of Rome, and from there to the Caelian, Aventine, Palatine, and Capitoline Hills. Where the Aqua Marcia had contact with water, it was coated with a waterproof mortar.

3 – The Early Empire

3.1 – Imperial Sculpture in the Early Empire

Augustan art served a vital visual means to promote the legitimacy of Augustus’ power, and the techniques he employed were incorporated into the propaganda of later emperors.

3.1.1 – Augustus

During his reign, Augustus enacted an effective propaganda campaign to promote the legitimacy of his rule as well as to encourage moral and civic ideals among the Roman populace.

Augustan sculpture contains the rich iconography of Augustus’s reign with its strong themes of legitimacy, stability, fertility, prosperity, and religious piety. The visual motifs employed within this iconography became the standards for imperial art.

3.1.2 – Ara Pacis AugustaE

Ara Pacis Augustae: The actual u-shaped altar sits atop a podium inside a square wall that demarcates the precinct’s sacred space.

The Ara Pacis Augustae, or Altar of Augustan Peace, is one of the best examples of Augustan artistic propaganda. Not only does it demonstrate a new moral code promoted by Augustus, it also established imperial iconography. It was commissioned by the Senate in 13 BCE to honor the peace and bounty established by Augustus following his return from Hispania (Spain) and Gaul; it was consecrated on January 30, 9 BCE.

The marble altar was erected just outside the boundary of the pomerium to the north of the city along the Via Flaminia on the Campus Martius. The actual u-shaped altar sits atop a podium inside a square wall that demarcates the precinct’s sacred space.

Ara Pacis Augustae: A detail from the processional scene on the south wall.

The north and south walls depict a procession of life-sized figures on the upper register . These figures include men, women, children, priests, lictors , and identifiable members of the political elite during the Augustan age. The elite include Augustus, his wife Livia, his son-in-law Marcus Agrippa (who died in 12 BCE), and Tiberius, Augustus’s adopted son and successor who would marry the emperor’s widowed daughter in 11 BCE. While the altar as a whole celebrates the Augustus as a peacemaker, this scene promotes him as a pious family man.

3.1.3 – Imperial Portraiture

Augustus very carefully controlled his imperial portrait. Abandoning the veristic style of the Republican period, his portraits always showed him as an idealized young man. These portraits linked him to divinities and heroes, both mythical and historical.

He is often shown with an identifiable cowlick that was originally shown on the portraits of Alexander the Great . His lack of shoes signifies his supposed humbleness despite the great power he possessed. Two portraits of him, one as Pontifex Maximus and the other as Imperator , depict two different personae of the emperor.

Augustus’s portrait as Pontifex Maximus shows him attired with a toga over his ever-youthful head, an attribute that serves to remind viewers of his own extreme piety to the gods.

Augustus: Portrayed as Pontifex Maximus.

The Augustus of Primaporta shows the influence of both Roman and Classical Greek works, including the Spear Bearer by Polykleitos and the Etruscan bronze Aule Metele. Assuming the role of imperator, Augustus wears military grab in a pose known as adlucotio, addressing his troops. Despite his poor health, which left him with a frail body, he appears healthy and muscular.

Cupid rides a dolphin at Augustus’ feet, a symbol of his divine ancestry. Cupid is the son of Venus, as was Aeneas, the legendary ancestor of the Roman people. The Julian family traced their ancestry back to Aeneas and, therefore, consider themselves descendants of Venus.

Augustus of Primaporta: The Augustus of Primaporta statue shows the influence of both Roman and Classical Greek works. Cupid rides a dolphin at Augustus’ feet, a symbol of his divine ancestry.

As Caesar’s nephew and adopted son, this use of iconography allows Augustus to remind viewers of his divine lineage. In addition to adopting the body language and attire of a general, the relief on the cuirass shows one of Augustus’ greatest victories—the return of the Parthian standards.

During the civil wars, a legion’s standards were lost when the legion was defeated by the Parthians . In a great feat of diplomacy, and curiously not military action, Augustus was able to negotiate the return of the standards to the legion and to Rome . Additional figures on the cuirass personify Roman gods and the arrival of Augustan peace.

3.1.4 – The Legacy of Augustan Sculpture

Upon the death of Augustus, Tiberius (14–37 CE) assumed the title of emperor and Pontifex Maximus of Rome. Like his father-in-law, Tiberius maintained a youthful appearance in his portraiture in sculpture.

A general in his pre-imperial career, Tiberius appears in a sculpture very similar to the Augustus of Primaporta. He wears military attire and stands erect in a dynamic contrapposto pose with his arm raised. Although he wears boots, which would appear to contradict the suggestion of humbleness seen in full-length sculptures of Augustus, his plain cuirass and the absence of religious iconography suggest a competent leader who does not promote his accomplishments or divine ancestry.

Full-length sculpture of Tiberius in military garb: Tiberius’ plain cuirass and the absence of religious iconography suggest a competent leader who does not promote his accomplishments or divine ancestry.

Like Augustus, who suffered from poor health, Claudius, who succeeded Caligula in 41 CE, was also infirm. In addition to health issues, Claudius lacked experience as a leader but quickly overcame this shortcoming as emperor.

During his reign, Rome annexed the province of Britannia (present-day England and Wales) and witnessed the construction of new roads and aqueducts . Despite these achievements, Claudius’s opponents still saw him as vulnerable, a situation that forced him to shore up his position almost constantly, resulting in the deaths of many senators. Perhaps this need to prove his competency in his role prompted him to commission a sculpture of himself as Jupiter, a sculpture that also bears striking similarities to the Augustus of Primaporta.

Claudius as Jupiter: Claudius holds a bowl (an offering to signify his piety) in one hand and a scepter-like object (to signify his power) in the other.

He continues the standard of the eternally youthful and healthy emperor begun by Augustus. His face and body are idealized. Like his predecessor, Claudius appears barefoot in a gesture of humility balanced with a symbol of divinity, in this case, an eagle to symbolize Jupiter. He wears a laurel crown as a metaphor of victory. While the positions of his arms and hand are similar to those of Augustus, Claudius holds a bowl (an offering to signify his piety) in one hand and a scepter-like object (to signify his power) in the other.

3.2 – Architecture of the Early Roman Empire

The Julio-Claudian and Flavian dynasties of the early Roman Empire oversaw some of the best-known building projects of the era.

3.2.1 – Introduction

The early Roman Empire consisted of two dynasties : the Julio-Claudians (Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero) and the Flavians (Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian). Each dynasty made significant contributions to the architecture of the capital city and the Empire.

The first Roman emperor, Augustus, enacted a program of extensive building and restoration throughout the city of Rome. He famously noted that he “found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble.”

This building program served the people of Rome by expanding public space , allocating places for trade and politics, and providing and improving the temples so the people could the serve the gods. As with his artistic iconography , this too became the standard that later emperors modeled their own building programs on.

3.2.2 – Basilica Julia

Basilica Julia: This is a computer generated image of the basilica, a large and ornate structure with two levels of arcades.

The basilica is a form of building that dates to the Roman Republic. Essentially it is the town hall in ancient Roman life, and many senators and emperors commissioned basilicas to commemorate their contributions to society.

In 46 BCE, Julius Caesar began the construction of the Basilica Julia, funded by spoils from the Gallic War, in the Roman forum . The basilica burned shortly after its completion, but Augustus oversaw its reconstruction and rededicated the building in 12 CE, naming the building after his great uncle and adoptive father.

The Basilica Julia housed the civil law courts and tabernae (shops), and provided space for government offices and banking. In the first century, it also housed the Court of the Hundred, which oversaw matters of inheritance.

It was a large and ornate structure with two levels of arcades . On both levels, an engaged column stood between each pair of arches. Tuscan columns adorned the ground level, while Roman Ionic columns adorned the second level. Full-length sculptures of men, possibly senators or other significant historical or political figures, stood under each arch on the second level and lined the roof above each engaged Ionic column. A similar pattern would appear on the Colosseum under the Flavians in the late first century CE.

3.2.3 – The Domus Aurea

In 64 CE, a fire erupted in Rome and burned ten of the fourteen districts in the city. Nero appropriated some of the newly cleared land for his own use. This land, located on the hills east of the Forum Romanum, became home to his new palatial structure known as the Domus Aurea, or the Golden House.

Nero’s complex included a private lake, landscaped gardens and porticoes, a colossal golden statue of himself, and rooms for entertaining that were lavishly decorated with mosaics , frescoes , and gold leaf . The surviving frescoes provide excellent examples of Pompeiian fourth- style painting, a fantastical style that inspired Renaissance grotesque when portions of the palace were discovered at the end of the 1400s.

Nero’s architects and engineers, Severus and Celer, designed the Domus Aurea and demonstrated some of the unique architectural shapes made possible through concrete construction. An octagonal hall testifies to the architects’ ingenuity. The octagonal room stands between multiple rooms, possibly for dining, and is delineated by eight piers that support a domed roof with an oculus that lit not only the hall but also the surrounding rooms. The octagonal hall emphasizes the role of concrete in shaping interior space, and the use of natural light to create drama.

Domus Aurea: The octagonal room with its surviving concrete dome and oculus.

Following Nero’s forced suicide in 68 CE, Rome plunged into a year of civil war as four generals vied against each other for power and Vespasian emerged victorious. After the year of warfare, Vespasian sought to establish stability both in Rome and throughout the empire. He and the sons who succeeded him ruled Rome for twenty-seven years.

Vespasian was succeeded by his son Titus, whose reign was short. Domitian, Titus’s younger brother, became the next emperor and reigned until his assassination in 96 CE. Despite being a relatively popular emperor with the people, Domitian had few friends in the Senate. His memory was condemned formally through damnatio memoriae —an edict that erased all memory and history of the person by removing their name from all documents and destroying all their portraits.

3.2.4 – Flavian Ampitheater

Upon his succession, Vespasian began a vast building program in Rome that was continued by Titus and Domitian. It was a cunning political scheme to garner support from the people of Rome.

Vespasian transformed land from Nero’s Domus Aurea into public buildings for leisure and entertainment, such as the Baths of Titus and the Flavian Amphitheatre. Nero’s private lake was drained and became the foundations for the amphitheater, the first permanent amphitheater built in the city of Rome. Before this time, gladiatorial contests in the city were held in temporary wooden arenas.

The amphitheater became known as the Colosseum for its size, but in also in reference to a colossal golden statue of Nero that stood nearby. Vespasian had the colossus reworked into an image of the sun god, Sol.

Flavian Amphitheater (Colosseum): The exterior of the Flavian Amphitheater or Colosseum, 70–80 CE, in Rome, Italy.

The building of the amphitheater began under Vespasian in 72 CE, and was completed under Titus in 80 CE. Titus inaugurated the amphitheater with a series of gladiatorial games and events that lasted for 100 days.

During his reign, Domitian remodeled parts of the amphitheater to enlarge the seating capacity to hold 50,000 spectators and added a hypogeum beneath the arena, for storage and to transport animals and people to the arena floor. The Colosseum was home not just to gladiatorial events—because it was built over Nero’s private lake, it was flooded to stage mock naval battles.

Like all Roman amphitheaters, the Colosseum is a free-standing structure, whose shape comes from the combination of two semi-spherical theaters. The Colosseum exists in part as a result of improvements in concrete and the strength and stability of Roman engineering, especially their use of the repetitive form of the arch. The concrete structure is faced in travertine and marble.

The exterior of the Colosseum is divided into four bands that represent four interior arcades. The arcades are carefully designed to allow tens of thousands of spectators to enter and exit within minutes. Attached to the uppermost band are over two hundred corbels which supported the velarium —a retractable awning to protect spectators from sun and rain. The top band is also pierced by a number of small windows, between which are engaged composite pilasters .

The three bands below are notable for the series of arches that visually break up the massive façade. The arches on the ground level served as numbered entrances, while those of the two middle levels framed statues of gods, goddesses, and mythical and historical heroes. Columns in each of the three Greek orders stand between the arches. The Doric order is located on the ground level, Ionic on the second level, and Corinthian on the third. The order follows a standard sequence where the sturdiest and strongest order is shown on bottom level, since it appears to support the weight of the structure, and the lightest order at the top. However, despite this illusion the engaged columns and pilasters were merely decorative.

3.2.5 – Arch of Titus

Arch of Titus: Via Sacra, Rome. 81-82 CE.

Following his brother’s death, Domitian erected a triumphal arch over the Via Sacra, on a rise as the road enters the Republican Forum. The Arch of Titus honors the deified Titus and celebrates his victory over Judea in 70 CE. The arch follows the standard forms for a triumphal arch, with an honorific inscription in the attic, winged Victories in the spandrels , engaged columns, and more sculpture which is now lost.

Inside the archway at the center of the ceiling is a relief panel of the apotheosis of Titus. Two remarkable relief panels decorate the interior sides of the archway and commemorate Titus’s victory in Judea.

[LEFT]: Triumph of Titus: This relief from the Arch of Titus that shows the triumphal procession for Titus upon his victory over Judea.

[RIGHT]: Sacking of Jerusalem.: This is a relief from the Arch of Titus.

The southern panel inside the arch depicts the sacking of Jerusalem. The scene shows Roman soldiers carrying the menorah (the sacred candelabrum) and other spoils from the Temple of Jerusalem.

The opposite northern panel depicts Titus’s triumphal procession in Rome, awarded in 71 CE. In this panel, Titus rides through Rome on a chariot pulled by four horses. Behind him a winged Victory figure crowns Titus with a laurel wreath. He is accompanied by personifications of Honor and Valor.

This is one of the first examples in Roman art of humans and divinities mingling together in one scene; indeed, Titus was deified upon his death. These panels were originally painted and decorated with metal attachments and gilding. The panels are depicted in high relief and show a change in technical style from the lower relief seen on the Ara Pacis Augustae.

[RIGHT]: Sacking of Jerusalem.: This is a relief from the Arch of Titus.

3.3 – Painting in the Early Roman Empire

Roman frescoes were the primary method of interior decoration and their development is generally categorized into four different styles.

3.3.1 – Introduction

Fayum mummy portrait: A mummy portrait of a young women found in the Fayum Necropolis, Egypt, from the second century CE.

Roman painters often painted frescoes, specifically buon fresco , a technique that involved painting pigment on wet plaster. When the painting dried, the image became an integral part of the wall. Fresco painting was the primary method of decorating an interior space. However, few examples survive, and the majority of them are from the remains of Roman houses and villas around Mt. Vesuvius.

Other examples of frescoes come from locations that were buried (burial protected and preserved the frescoes), such as parts of Nero’s Domus Aurea and at the Villa of Livia. These frescoes demonstrate a wide variety of styles. Popular subjects include mythology, portraiture, still-life painting, and historical accounts.

The surviving Roman paintings reveal a high degree of sophistication. They employ visual techniques that include atmospheric and near one-point linear perspective to properly convey the idea of space. Furthermore, portraiture and still-life images demonstrate artistic talent when conveying real-life objects and likenesses. The attention to detail seen in still-life paintings include minute shadows and an attention to light to properly depict the material of the object, whether it be glass, food, ceramics , or animals.

Roman portraiture further exhibits the talent of Roman painters and often shows careful study on the artist’s part in the techniques used to portray individual faces and people. Some of the most interesting portraits come from Egypt, from late first century BCE to early third century CE, when Egypt was a province of Rome.

These encaustic on wood panel images from the Fayum necropolis were laid over the mummified body. They show remarkable realism , while conveying the ideals and changing fashions of the Egypto-Roman people.

3.3.2 – Classification

At the end of the nineteenth century, August Mau, a German art historian, studied and classified the Roman styles of painting at Pompeii. These styles, known simply as Pompeian First, Second, Third, and Fourth Style, demonstrate the period fashions of interior decoration preferences and changes in taste and style from the Republic through the early Empire.

3.3.3 – First Style

Pompeian First Style: A Pompeiian first-style wall painting from the Samnite House. Fresco. Second century BCE. Herculaneum, Italy.

Also known as masonry style, Pompeian First Style painting was most commonly used from 200 to 80 BCE. The style is known for its deceptive painting of a faux surface; the painters often tried to mimic the richly veneered surfaces of marble, alabaster , and other expensive types of stone veneer.

This is a Hellenistic (Greek) style adopted by the Romans. While creating an illusion of expensive decor, First-Style painting reinforces the idea of a wall. The style is often found in the fauces (entrance hall) and atrium (large open-air room) of a Roman domus (house). A vivid example is preserved in the fauces of the Samnite House at Herculaneum.

3.3.4 – Second Style

Detail from the villa of P. Fannius Synistor: An architectural vista from a second-style wall painting in Boscoreale, Italy. c. 50–40 BCE.

Pompeiian Second Style was first used around 80 BCE and was especially fashionable from 40 BCE onward, until its popularity waned in the final decades of the first century BCE. The style is noted for its visual illusions. These trompe l’oeil images are intended to trick the eye into believing that the walls of a building have dissolved into the depicted three-dimensional space.

Wall frescoes were usually divided into three registers , with the bottom register depicting false masonry painted in the manner of the First Style, while a simple border was painted in the uppermost register. The central register, where the main scene unfolds, is the largest and the focal point of the painting. This space was an architectural zone that became the main component of Second-Style painting.

Typically, paintings that relied on near-perfect linear perspective to depict architectural expanses and landscapes that were painted on a human scale. The desired effect was to make the viewer feel as if, while in the room, he or she was physically transported to these spaces.

3.3.5 – Villa of Livia

Villa of Livia: A Second-Style garden vista from the Villa of Livia, in Primaporta, Italy, from the late first century BCE.

As the style evolved, the top and bottom registers became less important. Architectural scenes grew to incorporate the entire room, such as at the Villa of the Mysteries and the Villa of Livia.

In the case of the Villa of Livia, architectural vistas are replaced with a natural landscape that completely surrounds the room. The painting mimics the natural landscape outside the villa, depicting identifiable trees, flowers, and birds. Light filters naturally through the trees, which appear to bend in a slight breeze. Naturalistic elements like this, along with the flight of the birds and other details, help transport the occupant in the room into an outdoor setting.

3.3.6 – Villa of the Mysteries

At the Villa of the Mysteries, just outside of Pompeii, there is a fantastic scene filled with life-size figures that depicts a ritual element from a Dionysian mystery cult. In this Second-Style example, architectural elements play a small role in creating the illusion of ritual space. The people and activity in the scene are the main focus .

The architecture present is mainly piers or wall panels that divide the main scene into separate segments. The figures appear life-size, which brings them into the space of the room.

Villa of the Mysteries: One wall on the ritual scene depicted at the Villa of Mysteries, in Pompeii, Italy, c. 60–50 BCE.

The scene wraps around the room, depicting what may be a rite of marriage. A woman is seen preparing her hair. She is surrounded by other women and cherubs while a figure, identified as Dionysus , waits. The ritual may reenact the marriage between Dionysus and Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos.

All the figures, except for Dionysus and one small boy, are female. The figures also appear to interact with one other from across the room. On the two walls in one corner, a woman reacts in terror to Dionysus and the mask over his head. On the opposite corner, a cherub appears to be whipping a woman on the adjoining wall. While the cult aspects of the ritual are unknown, the fresco demonstrates the ingenuity and inventiveness of Roman painters.

3.3.7 – Third Style

Third-Style wall painting: Detail of a Third-Style wall painting from the Villa of Agrippa Postumus in Boscotrecase, Italy, c. 10 BCE.

Third-Style Pompeiian painting developed during the last decades of the first century BCE. It was popular from 20 BCE until the middle of the first century CE. During this period, wall painting began to develop a more fantastical personality.

Instead of attempting to dissolve the wall, the Third Style acknowledges the wall through flat, monochromatic expanses painted with small central motifs that look like a hung painting. The architecture painted in Third-Style scenes is often logically impossible. The wall is frequently divided into three to five vertical zones by narrow, spindly columns and decorated with painted foliage, candelabra, birds, animals, and figurines .

Often these creatures and people were derived from Egyptian motifs, resulting from a contemporary Roman fascination with Egypt known as Egyptomania , following the defeat of Cleopatra at Actium and the annexation of Egypt in 30 BCE.

3.3.8 – Fourth Style

The Pompeian Fourth Style became popular around the middle of the first century CE. While considered less ornate than the Third Style, the Fourth Style is more complex and draws on elements from each of the three previous styles.

In this style, masonry details of the First Style reappear on the bottom registers, and the architectural vistas of the Second Style are once more fashionable, although infinitely more complex than their Second-Style predecessors. Fantastical details, Egyptian motifs, and ornamental garlands from the Third Style continued into the Fourth Style. Large pictures, connected to each other by a program or theme, dominated each wall, such as those in the House of the Vettii.

3.3.9 – House of the Vettii

[LEFT]: Daedelaus and Pasiphaë: Daedalus presents Pasiphaë with a wooden heifer.

[RIGHT]: Fourth Style: A Fourth- Style wall fresco in the Ixion Room of the House of the Vettii.

Many rooms in the House of the Vettii are lavishly painted. Each triclinium is themed and painted in the Fourth Style. Each panel in the room follows the room’s theme, providing visual entertainment and a narrative during dining.

The Ixion Room, for instance, is a model of Fourth-Style wall painting. Within each red panel is a scene that depicts myths where the main character commits a major slight. One panel is dedicated to Ixion, who refused to pay a dowry and murdered his father-in-law. He also lusted after Zeus’s wife, betraying the relationship between guest and host.

Another panel depicts Daedalus presenting a wooden cow to Pasiphaë, the wife of King Minos, so she could relieve her lust for a white bull. From this union, Pasiphaë birthed the Minotaur , a half-man, half-bull monster. Another Fourth-Style triclinium depicts scenes from the lives of Hercules and Theseus.

[RIGHT]: Fourth Style: A Fourth- Style wall fresco in the Ixion Room of the House of the Vettii.

3.3.10 – House of the Tragic Poet

The Sacrifice of Iphigenia: A panel in the House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii, Italy, c. 60–65 CE.

The atrium of the House of the Tragic Poet includes a series of paintings that depict scenes from the Trojan War. The panels on the walls depict scenes that appear to be interrelated. As in the panels that decorate the House of the Vettii, the subject matter in the paintings in the House of the Tragic Poet are interrelated based on a common theme. Scholars believe these themes were carefully crafted not only to relate stories, but also to depict the virtues of the house’s owner.

Two panels on the south wall relate the beginnings of the Trojan War. One panel is of Zeus and Hera on Mount Ida. Another, badly damaged, appears to be a scene of the Judgment of Paris. These panels relate the beginnings of the Trojan War while portraying womanly ideals.

Two pairs of scenes, set across from each other, depict different, interrelated themes. The abduction of women is one theme visible in one image of Helen with Paris leaving for Troy. Another image portrays the abduction of Amphitrite by Poseidon. In both cases, a man abducts a woman.

The other two scenes deal with the argument between Achilles and Agamemnon, which begins the story of the Illiad. Of these two scenes, one depicts Achilles with Agamemnon, while the other depicts Achilles returning Briseis, his lover and captive, to his commander, Agamemnon.

A final image, found in the peristyle , depicts the Sacrifice of Iphigenia. All of these paintings are related to one another through themes such as marriage, womanly virtue, and the Trojan War.

3.3.11 – Riot at the Ampitheatre

Depiction of a riot at the amphitheatre at Pompeii: In 59 CE, a riot broke out between the citizens of Pompeii and the citizens of nearby Nuceria during a gladiatorial event. The brawl in the amphitheater resulted in serious injuries between both parties and the banning of all gladiatorial events for ten years.

While the above examples of Fourth-Style painting depict scenes from mythology, at least one contemporary scene is represented in a surviving fresco. In 59 CE, a riot broke out between the citizens of Pompeii and the citizens of nearby Nuceria during a gladiatorial event. The brawl in the amphitheater resulted in serious injuries between both parties and the banning of all gladiatorial events for ten years.

A fresco from Pompeii that depicts the event has also survived. The fresco depicts the Pompeiian amphitheater, with its distinctive exterior staircase, as well as an awning, the velarium . It also depicts the riot occurring both inside the arena and on the grounds surrounding the amphitheater.

3.4 – Architecture at Pompeii

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE preserved many structures in the city of Pompeii, allowing scholars a rare glimpse into Roman life.

3.4.1 – Mount Vesuvius and the Preservation of Pompeiian Architecture

During the Roman Republic and into the early Empire, the area today known as the Bay of Naples was developed as a resort-type area for elite Romans to escape the pressure and politics of Rome . The region was dominated by Mt. Vesuvius, which famously erupted in August 79 CE, burying and preserving the cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii, along with the region’s villas and farms.

When Vesuvius erupted on August 25, a cloud of ash spewed south, burying the cities of Pompeii, Nuceria, and Stabiae. While not everyone left prior to the eruption, archaeological evidence shows that people did leave the city. Some houses give the impression of having been packed up and in some cases furniture and objects were excavated jumbled together. Other objects of value appear to have been buried or hidden. There is evidence of people returning after the eruption to dig through the remains—either recovering lost goods or looting for valuables.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius: The black and gray areas show the direction in which the wind blew the ash and pyroclastic clouds.

In Pompeii, an ash flow suffocated the remaining population and allowed all organic matter to decompose. However, where bodies and other organic objects (from bodies to wooden architectural frames) once lay or stood, empty cavities within the ash remained and preserved their outer forms .

A pyroclastic flow of superheated gas and rock went west to the coast and the city of Herculaneum. Unlike the ash blanket of Pompeii, the pyroclastic flow in Herculaneum petrified organic material, ensuring the preservation of human remains and wood, including the preservation of wooden screens, beds, and shelving. Many of the frescoes , mosaics , and other non-organic materials in both the ash and pyroclastic flows were preserved until their excavation in the modern period.

3.4.2 – Residential Architecture at Pompeii

3.4.2.1 – The Roman Domus

The Roman domus, or house, played two important roles in Roman society: as a home and as a place of business for patricians and wealthy Romans. To facilitate this dual functionality, the domus had a distinct set of rooms that could be used as either public or private spaces. While no modern domus adheres to the standard model of a domus, many Roman houses, both small and large, have nearly all of these different rooms.

Roman Domus: A standard plan of a Roman domus.

The design of the domus reflects the Roman patronage where a client is protected by a wealthy patron, and in return supports the actions and estate of the patron. Many of a patron’s clients would be freedmen or other plebeians and lesser patricians.

The domus is often set back from the main street, and tabernae (shops) line the streets on either side of the house’s main entrance. Clients entered the house through the fauces (Latin for jaw), which was a narrow entryway into an atrium.

The atrium was the most important part of the house since it was the spot where clients and guests were greeted. It often included an impluvium, or basin that collected rain water. The roof did not cover the impluvium. The open space above the basin was called the compluvium.

The atrium was often richly decorated with thematic frescos and images of the patron’s ancestors. Cubicula , or rooms, lined the atrium, and at the far end was the tablinum. The tablinum functioned as the office of the patron and was where he met with his clients during the morning ritual of salutatio. The tablinum often provided a glimpse into the private sphere of the house, which was set behind the office.

Typically, the front half of the house served as public space, while the back of the domus was reserved for the more private functions of the family. In the back of the house, beyond the tablinum, would be one or more triclinium (plural: triclinia), or dining rooms. The dining rooms were lavishly decorated and typically furnished with dining couches and a low table.

A peristyle—a colonnaded courtyard—was usually the main feature of the back of the house. It could contain gardens and even a pool and provided light as well as shade and breeze for hot summer days. Other features of the domus, include alae (open rooms) with an unknown function, kitchens (culina), and additional rooms for work, sleeping, and servants.

3.4.3.2 – Domus at Pompeii

Each domus throughout Pompeii represents the various ways the standard components of a domus were used to create unique floor plans that showcase the status and wealth of the owner.

The large complex of the House of the Faun encompasses an entire city block. This domus has two atria, each with its own fauces, although with two peristyles of different sizes. In essence, the House of the Faun was a private villa despite its urban setting.

House of the Faun: Ground plan of the House of the Faun in Pompeii, Italy.

Two houses, the House of the Vettii and the House of the Tragic Poet—both previously discussed for their wall paintings—are simpler constructions than the House of the Faun, but both house plans still readily depict the wealth of the household.

House of the Vettii: Ground plan of the House of the Vettii in Pompeii, Italy.

Visitors entering the House of the Vettii were greeted by a frescoed image of Priapus, an image that portrayed the wealth and luck of the two bachelors who lived inside. The main attributes of their house were the atrium and the large garden peristyle, surrounded by decorated triclinium and a garden complete with fountains, statues, and flowers. While this house had fewer public-private access restrictions than the standard domus, it did include the main attributes of a traditional Roman house.

House of the Tragic Poet: Ground plan of the House of the Tragic Poet.

The House of the Tragic Poet was small but maintained the public-private access characteristic of the traditional domus. The fauces was especially noted for its mosaic image of a dog, complete with the warning “Cave canem,” or, roughly, “Beware of dog.” The fauces led the guest into the atrium and the tablinum, which divided the public front of the house from the private back of the house, where a small peristyle and a frescoed triclinium were located.

3.4.4 – Public Architecture

The ash cloud that blanketed Pompeii in 79 CE preserved public buildings, as well as domi. Among the best preserved are the amphitheater, the Temple of Isis, and the Suburban Baths.

3.4.5.1 – Ampitheater of Pompeii

Amphitheater of Pompeii: Built c. 70 BCE.

The Amphitheater of Pompeii is the oldest surviving Roman amphitheater. Built around 70 BCE, the current amphitheater is the earliest Roman amphitheater known to have been built of stone. Previous amphitheaters were constructed of wood.

The design is seen by some modern crowd control specialists as near optimal. Similar to the Colosseum, but constructed over a century later, its arcaded exterior appears to have been conducive to efficient evacuation. Its washroom, located in the neighboring wrestling school, has also been cited as an inspiration for better bathroom design in modern stadiums.

Amphitheatre of Pompeii: The interior, with its tiered seating, shows the influence of Greek designs.

Derived from the Greek words amphi (on both sides) and theatron (a place for viewing), an amphitheater combines two theaters into a circular or ovoid form. The interior of the amphitheater at Pompeii resembles two Greek theaters, with its tiered seating overlooking a central staging area. Still structurally and acoustically sound, the amphitheater was the site of notable rock concerts in 1971 and 2016.

3.4.5.2 – Temple of Isis

Temple of Isis: The temple’s design combines Roman, Greek, and Egyptian architectural elements.

Roman culture was accommodating of most of the religious beliefs of its conquered peoples, and often built temples and sanctuaries to non-Roman deities and incorporated them into their own pantheon. One such example is the Temple of Isis, dedicated to the Egyptian mother goddess.

The principal devotees of this temple are assumed to be women, freedmen, and slaves. Initiates of the Isis mystery cult worshiped a compassionate goddess who promised eventual salvation and a perpetual relationship throughout life and after death.

The temple’s design combines Roman, Greek, and Egyptian architectural elements. It is surrounded by brick columns faced with plaster in a stylized reed motif often found on Egyptian columns. Their general shape recalls both the Doric and Tuscan orders.

Like typical Roman temples, the portico and cella rest on a raised platform connected to the ground by a central stairway. The columns on the portico appear to have been Tuscan. To either side of the cella is an arched niche flanked by either Corinthian or Composite pillasters.

3.4.5.3 – Suburban Baths

Suburban Baths: Built against the city walls, this structure served as a public bath house for the residents of Pompeii.

The Suburban Baths (c. late first century BCE), built against the city walls, served as a public bath house for the residents of Pompeii. The entrance to the Baths is through a long corridor that leads into the dressing room.

Excavation of the Baths revealed only one set of dressing rooms and has led archaeologists to believe that both men and women shared this facility. The dressing room then led to the tepidarium (lukewarm room), followed by the caldarium (hot room), both of which were standard in public baths throughout the empire.

4 – The Nervan-Antonines

4.1 – Architecture under the Nervan-Antonines

The emperors Trajan and Hadrian were the two most prolific emperors who constructed buildings during the Nervan-Antonine dynasty.

4.1.1 – Public Building Programs

Public building programs were prevalent under the emperors of the Nervan-Antonine dynasty . During this period of peace, stability, and an expansion of the empire’s borders, many of the emperors sought to cast themselves in the image of the first imperial builder, Augustus. The projects these emperors conducted around the empire included the building and restoration of roads, bridges, and aqueducts . In Rome , these imperial building projects strengthened the image of the emperor and directly addressed the needs of the citizens of the city.

4.1.2 – Trajan’s Forum

Trajan’s Forum was the last of the imperial fora to be built in the city. The forum’s main entrance was accessed from the south, near to the Forum of Augustus as well as the Forum of Caesar (which Trajan also renovated). The Forum of Augustus might have been the model for the Forum of Trajan, even though the latter was much larger. Both fora were rectangular in shape with a temple at one end. Both appear to have a set of exedra on either side.

Plan of the Forum of Trajan and Trajan’s Markets: Trajan built the forum and markets around the same time from 106 to 113 CE.

Trajan built his forum with the spoils from his conquest of Dacia. The visual elements within the forum speak of his military prowess and Rome’s victory. A triumphal arch mounted with an image of the emperor in a six-horse chariot greeted patrons at the southern entrance.

In the center of the large courtyard stood an equestrian statue of Trajan, and additional bronze statues of him in a quadriga lined the roof of the Basilica Ulpia, which transected the forum in the northern end. This large civic building served as a meeting place for the commerce and law courts. It was lavishly furnished with marble floors, facades , and the hall was filled with tall marble columns .

The Basilica Ulpia also separated the arcaded courtyard from two libraries (one for Greek texts, the other for Latin), the Column of Trajan, and a temple dedicated to the Divine Trajan.

4.1.3 – Trajan’s Markets

Trajan’s Markets: Trajan’s Markets as they stand today.

Trajan’s markets were an additional public building that the emperor built at the same time as his forum. The markets were built on top of and into the Quirinal Hill. They consisted of a series of multi-leveled halls lined with rooms for either shops, administrative offices, or apartments. The markets follow the shape of the Trajan’s forum.

A portion of them are shaped into a large exedra, framing one of the exedra of the forum. Like Trajan’s forum, the markets were elaborately decorated with marble floors and revetment, as well as decorative columns to frame the doorways.

4.1.4 -Apollodorus of Damascus

Many of Trajan’s architectural achievements were designed by his architect, Apollodorus of Damascus. Apollodorus was a Greek engineer from Damascus, Syria. He designed Trajan’s forums and markets, the Arch of Trajan at Benevento, and an important bridge across the Danube during the campaigns against the Dacians.

Unfortunately for Apollodorus, Trajan’s heir Hadrian also took an interest in architecture. According to Roman biographers, Apollodorus did not appreciate Hadrian’s interests or architectural drawings and often discredited them. Upon the succession of the new emperor, Apollodorus was dismissed from court.

4.1.5 – Hadrian’s Pantheon

Hadrian’s most famous contribution to the city of Rome was his rebuilding of the Pantheon, a temple to all the gods, that was first built by Agrippa during the reign of Augustus. Agrippa’s Pantheon burned down in the 80s CE, was rebuilt by Domitian, and burned down again in 110 CE.

Hadrian’s Pantheon still remains standing today, a great testament of Roman engineering and ingenuity. The Pantheon was consecrated as a church during the medieval period and was later used a burial site.

Elevation drawing of the Pantheon: The Pantheon is an architectural innovation with a magnificent concrete, unreinforced dome.

The most unusual aspect of the Pantheon is its magnificent coffered dome, which was originally gilded in bronze. The concrete dome, which provided inspiration to numerous Renaissance and Neoclassical architects, spans over 142 feet and remains the largest unreinforced dome today. It stands due to a series of relieving arches and because the supportive base of the building is nearly twenty feet thick.

The cylindrical drum on which the dome rests consists of hollowed-out brick filled with concrete for extra reinforcement. At the center of the dome is a large oculus that lets in light, fresh air, and even rain. Both the oculus and the coffered ceiling lighten the weight of the dome, allowing it to stand without additional supports.

Pantheon: Hadrian rebuilt the Pantheon of Agrippa in 118–125 CE.

The Pantheon takes its shape from Greek circular temples, however it is faced by a Roman rectangular portico and a triangular pediment supported by monolithic granite columns imported from Egypt. The portico, which originally included a flight of stairs to a podium, acts as a visual trick, preparing viewers to enter a typical rectangular temple when they would instead be walking into a circular one.

A dedicatory inscription is carved in the entablature under the pediment. The inscription reads as the original inscription would have read when the Pantheon was first built by Agrippa. Hadrian’s decision to use the original inscription links him to the original imperial builders of Rome.

4.1.6 – Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli

Hadrian traveled extensively during his reign and was frequently exposed to a variety of local architectural styles. His villa at Tivoli (built during the second and third decades of the second century CE) reflects the influence of styles found in locations such as Greece and Egypt.