hey poured gold down his throat, cut off his head, and sent it back as a warning to others.

No, this is not a scene from the latest episode of Game of Thrones; this was the passing of Marcus Licinuis Crassus in 53 BC.[1] Rome’s richest man, a member of the First Triumvirate with Julius Caesar, and the man responsible for putting down the pirates that menaced the Mediterranean, met his ignoble end fighting the greatest challenge the Romans ever faced in the east: Parthia.

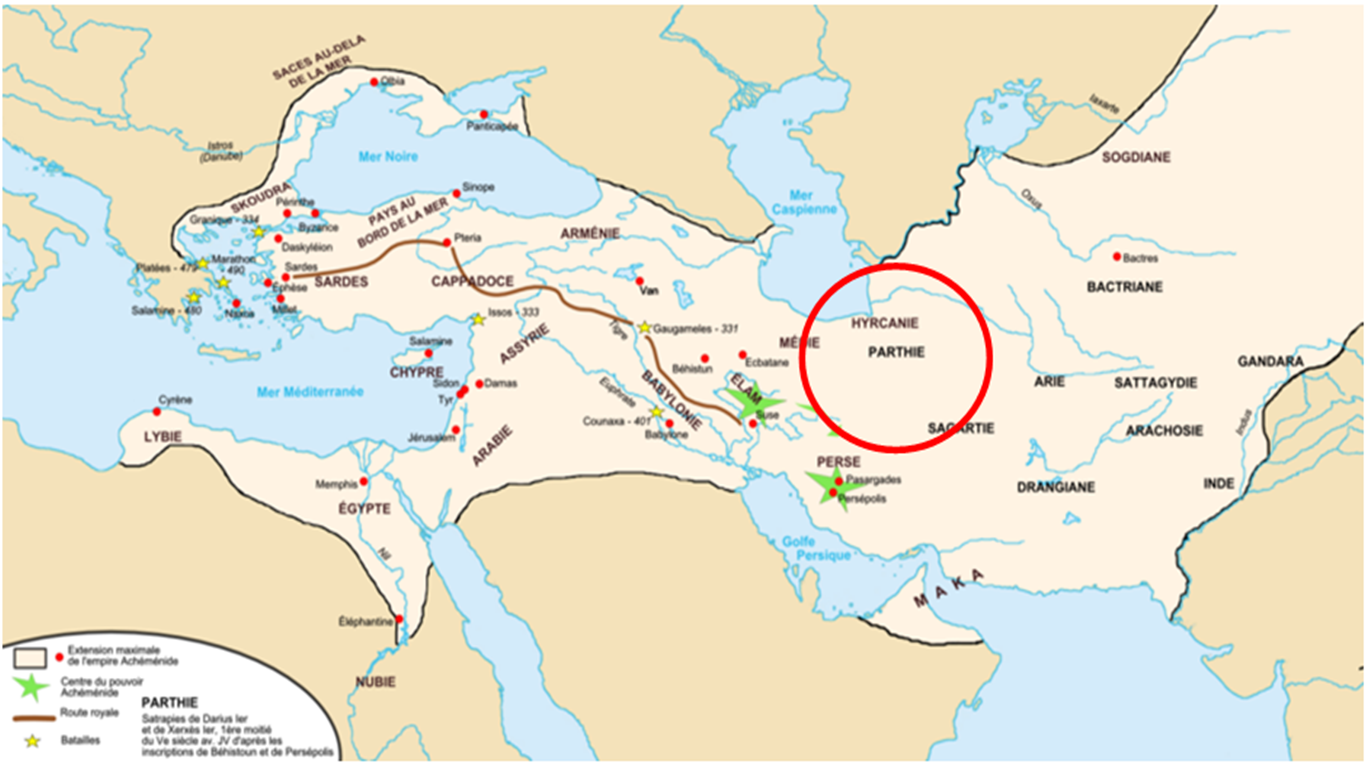

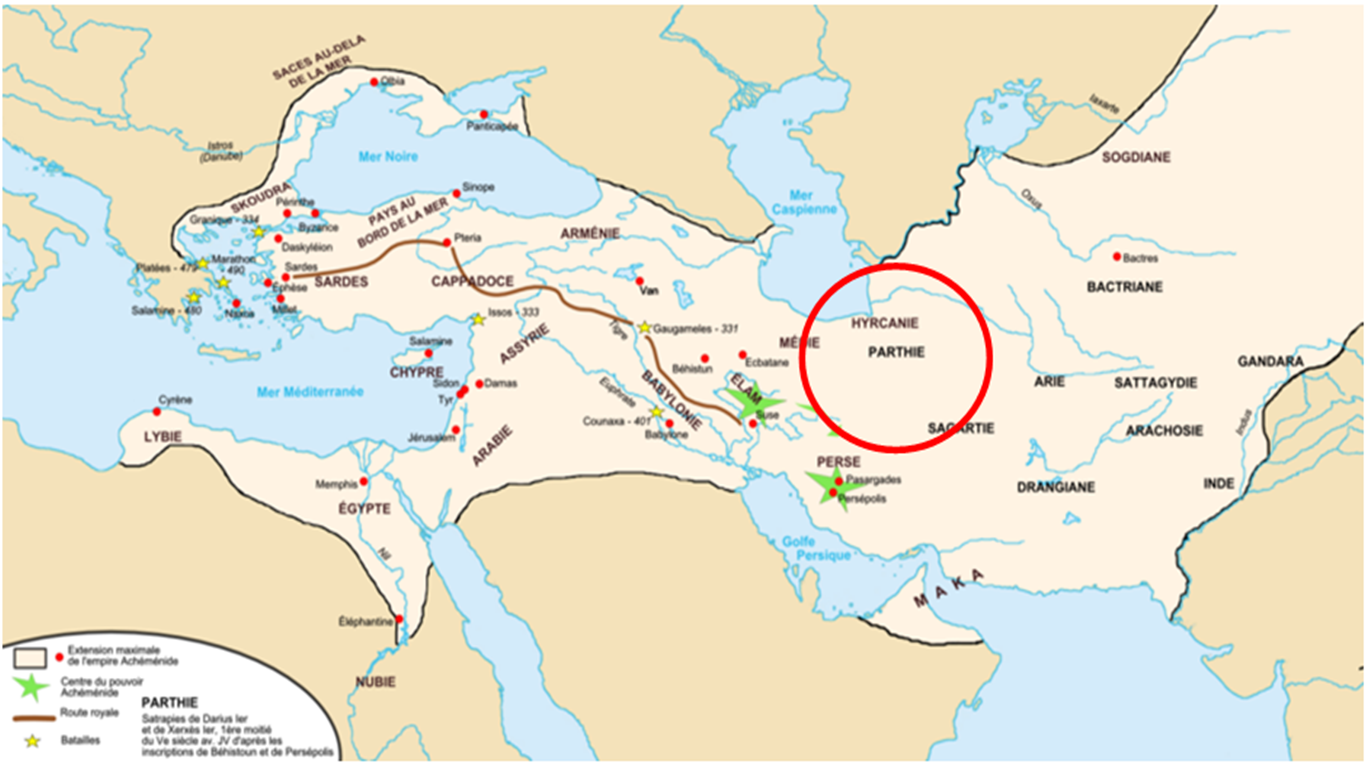

Map of the Achaemenid Persian Empire at its height with the region of Parthia marked in a red circle (Wikimedia Commons)

Parthia marked in a red circle (Wikimedia Commons)

Parthia marked in a red circle (Wikimedia Commons)

Parthia marked in a red circle (Wikimedia Commons)

Persia was the preeminent military, political, and cultural power in the ancient world from 550 B.C. to 330 B.C. With its heartland in modern day Iran, its empire spanned from Afghanistan to Turkey at its apex. It all came crashing down in spectacular fashion when Alexander of Macedon rose to power and led a ruthlessly efficient military machine on a path of conquest that brought him all the way to the Indus River. He tried his hardest to unify the Persian state with his own but, when he died at the age of 33 in 323 B.C., his empire immediately collapsed into a host of warring factions. Three of his Greek generals went on to found the three largest states in the Eastern Mediterranean by the time Rome rose: the Seleucids in Turkey and Syria, the Antripatrids (later the Antigonids) in Greece, and the Ptolemians in Egypt. In the Persian heartland, however, ethnic Persians waging a proto-nationalist campaign kicked out the remnants of the Greek invaders. Known as Parthians due to the origins from the titular province in north-eastern Iran, they established a small state that expanded outward as the Alexandrian generals quarreled with one another.

For centuries after his death, every Greek warlord in the Western World claimed their legitimacy through Alexander and the desire to rebirth his Empire. Rome, too, took up this mantle as it expanded eastward into the Greek mainland. Beginning first in Greece and Macedonia, they waged a brutal war with the beleaguered Seleucids and conquered all the territory they possessed in the modern Middle East. This brought Rome’s borders right onto those of Parthia. Both were rising states with expansionist ambitions and a border that sat on porous, easily invadable territory. The stage was set for an epic confrontation between the two great powers.

Map of the Roman-Parthian border with the location of Carrhae shown in a red circle (University of Guelph)

Unfortunately for Rome, this manifested in the ill-fated expedition of the afore-mentioned Crassus in 54 BC. The expedition met its unfortunate end on the plains of Carrhae in south-eastern Turkey along the Syrian border.

How did the Parthians manage to resist Rome for so long? Their success rested on three key disparities between them and their Roman opponents:

1) Assymmetric Military Advantage

A Roman Legionnaire (left) facing his greatest threat since Hannibal: Parthian horse archers using the Parthian Shot (Wikimedia Commons)

The Roman legion was the paragon of military efficiency in its day. The strict discipline, advanced military technology, and sheer numbers were widely feared even before they began leaving the Italian peninsula. It was by no means a perfect force, as its travails against Hannibal in preceding centuries demonstrated, but the system itself was markedly better than any other fielded even with bad generalship. How then was it so ineffective against Parthia?

Unlike the other opponents the Romans fought in the preceding six centuries, the great bulk of the Parthian army were horse archers rather infantry or melee cavalry. Noted for the infamous “Parthian Shot,” their horsemen would rush forward to engage Roman infantry, retreat, then abruptly turn in their saddles to fire a shot directly behind them. The slow, methodical legionnaires were then rendered ineffective since they could not physically reach their assailants. The horse archer can be equated with modern fears about Medium-Range Ballistic Missiles (MRBMs); they were mobile, highly survivable, and could take out slower assets with near impunity.

These techniques were perfect for the open terrain on the Roman-Parthian border. If the topography had been less open, such as the forests of Gaul or Germania, Parthian tactics would have been less effective. The Parthians, though, did not need an army that could fight on different terrain because that is not where they needed to fight nor chose to fight. This brings us to the second advantage Parthia held over the Romans.

2) Strategic Focus

The Parthians never harbored ambitions to conquer Rome; their strategy consisted of resisting Roman incursions and making their own when Rome was politically weak (see discussion below). Since the Parthians did not commit their resources into futile all-or-nothing fights with Rome or engage them on disadvantageous terrain, they always maintained a strong conventional deterrent that altered Rome’s calculus away from intervention.

Map showing the Parthian Empire in relation to the territory of the Scythian nomads. Without a central government, the Scythian tribes could only pose occasional threats in Parthia’s east (Wikimedia Commons)

The Parthians also had the strategic benefit of having fewer serious external competition; its western border was solely with Rome and the neutral kingdom of Armenia (the site of many proxy wars between Rome and Parthia). To their east were far weaker and divided opponents, namely the Scythians and Bactrians. Rome, on the other hand, was beset by strong enemies on all sides. These included: restive tribes in Gaul and the Danube region, lingering discontent in Numidians North Africa, a still-unitary Egypt, and a vascillating client state in northern Turkey. These challenges both demanded military resources and political attention to effectively control. Even if Rome had more money and soldiers than the Parthians, only so many of them could be dedicated toward fighting the Parthians.

3) Stronger Political Core

(From the Left) Marcus Licinuis Crassus, Julius Caesar, and Marc Antony. All of the men tried to invade Parthia. The first one actually crossed the border and was killed. The other two were killed by Romans before even getting there (Wikimedia Commons and the Musee Des Augustins)

Parthian politics were cold and brutal. Succession crises were common and factions killed one another as they vied for the Parthian crown. There were even instances of Parthian claimants to the throne finding refuge in Rome, like exiled dictators, waiting for the opportune moment to return.

Roman politics during the late Republic and early Empire made Parthia look like Switzerland. The invasion of Parthia planned by Julius Caesar in 44 BC to avenge the death of Crassus (and punish the Parthians for their support of his rival, Pompey) was cancelled when Caesar fell to assassins’ blades on the Ides of March. The resulting civil war claimed thousands of Roman lives both on the battlefield and during the infamous proscriptions during which whatever faction happened to hold power would murder people and then “nationalize” their assets. After years of civil war, Rome finally found its footing under the Second Triumvirate. Marc Antony amassed his own army to take on the Parthians and managed to expel them from Syria in 33 BC only to have to turn around to fight his political partner Octavian in yet another civil war.

Octavian eventually succeeded in unifying the Roman state under his autocratic rule but, by then, he was in no position to challenge any external power. Crippling debts were poised to ruin the state. Opposing factions, though cowed by Augustus’ power, still opposed him behind the scenes. Octavian was forced to reduce to total number of legions to consolidate his hold on the Empire and reduce the risk of another civil war. Rather than risking another Parthian encounter in his weakened state, Octavian instead signed a landmark peace agreement that designated permanent borders in exchange for the legionary standards lost during Crassus’ expedition 33 years earlier. The Roman-Parthian drama would continue in fits and starts over the remainder of their very existences but, after that fateful treaty signed by Augustus, Rome finally admitted that it would fully never replicate Alexander’s conquest of Persia.

The cruel lesson for the United States to take from the Roman experience with Parthia is that an adversary with technology designed specifically to defeats its army, combined with stronger political will, is bound to come out on top of any conflict. Defeat does not just come on the battlefield. Just like Rome, the United States has a great number of serious threats: a bellicose Russia, an increasingly-assertive China, a still-problematic Iran, and trans-national terrorism. Unlike many of these antagonists (and the Parthians before them), the United States does not have the luxury of dedicating its resources to countering just one of these threats. The United States’ political system, after years of war and deep partisanship that conjures images of Caesar’s Rome, is brittle and unable to tackle any of these challenges. The lesson from Parthia is that to defeat the United States is merely to outlast it and negotiate for what you truly want.

Fortunately, for the United States, the peace under Augustus is not the end of the story. Over the following two centuries, the tables would turn and the Parthians’ political structure collapsed. Years of dynastic feuds and rival claimants to the throne made Parthia vulnerable to strong Roman Emperors such as Trajan (115 A.D.) and Septimus Severus (198 A.D.). The Parthian state was overthrown by internal revolution and a new Persian dynasty took its place. The final lesson for the United States is this: it is never too late to recalibrate and nothing is over until it is over.

Matthew Merighi is a civilian employee with the United States Air Force’s Office of International Affairs (SAF/IA) currently transitioning to pursue a Masters’ Degree at the Fletcher School. His views do not reflect those of the United States Government, Department of Defense, or Air Force but hopes his country can stand up to the Parthians.

Note

[1] There is no concrete proof that the gold-pouring incident is true apart from the reports of the Roman historian Cassius Dio but it definitely gets the point across.

No comments:

Post a Comment