MINOANS

The Minoans were arguably Europe's first great civilization. They originated on the island of Crete around 3000 B.C. and flourished there from 2000 B.C. to 1,400 B.C. While most of Europe was still in the Stone Age the Minoans created cities with magnificent palaces and comfortable townhouses with terra cotta plumbing; traded throughout the Mediterranean and the Aegean with a huge fleet of ships; and developed a writing system. The Minoans are named by British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans after the legendary King Minos, son of Zeus and Europa, who is said to have lived on Crete. [Source: Joseph Judge, National Geographic, February 1978]

The Minoans were arguably Europe's first great civilization. They originated on the island of Crete around 3000 B.C. and flourished there from 2000 B.C. to 1,400 B.C. While most of Europe was still in the Stone Age the Minoans created cities with magnificent palaces and comfortable townhouses with terra cotta plumbing; traded throughout the Mediterranean and the Aegean with a huge fleet of ships; and developed a writing system. The Minoans are named by British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans after the legendary King Minos, son of Zeus and Europa, who is said to have lived on Crete. [Source: Joseph Judge, National Geographic, February 1978]

A lack of depictions of war and the fact that few fortifications have been found around Minoan cities and has led archaeologists to believe that warfare was uncommon in Minoa and the Minoans were a peaceful people that devoted their attentions to the arts not the military. They made some of the world's first frescoes, jewelry with precious stones, and thin-shelled pottery. The also left behind a written language that was undeciphered until the 1990s.

Minoa was a Bronze Age culture and a contemporary of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia and Babylon. The ancestors of the Greeks and Minoans are believed to have been the Luvians, an 8000-year-old people from the hills of Anatolia. The Minoan golden age was between 1600 and 1450 B.C., when large palaces were built in Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia and Zakros and Minoa had colonies on the islands of Kythera and Rhodes and trading posts as far away as Syria. At that time Egypt was at its height under Ramses III and the Trojan War and the Israelite's Exodus to the Promised Land was still 300 years in the future.

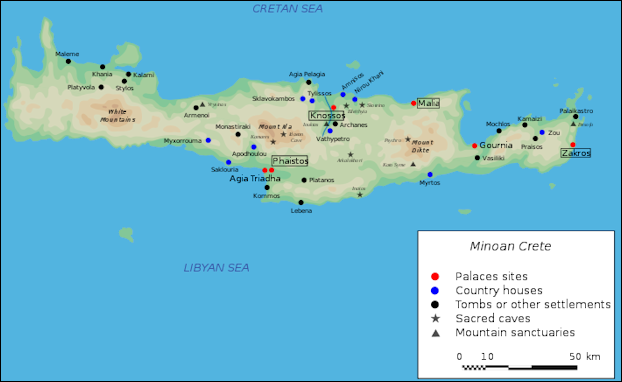

Crete

Minoan ceramicsCrete (12 hours from Piraeus, 6 hours from Santorini) is the largest and southernmost island in Greece, and the home of the Minoans (2600 B.C. to 1450 B.C.) the first great civilization of Europe. They preceded classical Greece by 2000 years and where to believed to have been snuffed out in 1450 B.C. by the a volcanic eruption four times more powerful than Krakatoa.

Ruins of Minoan Culture are found Knossos, Phaestos, Malia and Kato Zakros. Most of Crete's other attractions are natural. In the south there are lovely beaches, in the interior are massive rocky mountains that are sometimes covered in snow and in the west there is the famous Samarian Gorge.

Crete was at one time covered with oaks, chestnuts, pine trees and cypresses. The hills of the island are now largely denuded.

Periods of Minoan History

Minoan civilization began evolving around 3000 B.C. around the start of the Bronze Age. At that time the early Minoans used bronze and copper along with bone and stone weapons. The first examples of artistic decorations on pottery and walls appeared around 2850 B.C. By 2500 B.C. they were producing decorative jewelry and stone vases. Archaeologists now mark the period between 3000 B.C. and 2000 B.C. as the Early Period of Minoan civilization.

The Middle Period of Minoan civilization lasted from around 2000 B.C. to 1700 B.C. Early flush toilets were developed around 2000 B.C. and early Minoan writing first appeared between 2000 to 1850 B.C. The Late Period lasted from around 1700 B.C. to 1450 B.C. Fires destroyed many palaces in 1450 B.C. The last palaces in Knossos was abandoned by 1300 B.C. . The destructive Thera eruption occurred in 1645 B.C.

The period between 1450 and 100 B.C. has been labeled the Sub-Minoan, a long period of decline that culimated with the end of Minoan culture in 1050 B.C.

Minoan Crete

Knossos

Knossos (6 kilometers south of Iraklion) was the capital of the Minoan empire, Europe's first great civilization. It is also where you'll find a palace reportedly used by King Minos. There is no evidence however of the legendary Minotaur or the Labyrinth, despite the fact the ruins sometimes resemble a maze.

Knossos attracts more tourist than any other archeological site in Greece save the Acropolis and the Parthenon. It attracts about a million visitors a year. At first glance you'll be amazed be these "ruins." They aren't just pieces of marble piled on top of one another; they hold together like real buildings and what is more the columns are bright red an the cross beams are yellow.

Unlike most archeological sites Knossos was reconstructed and painted. Some of the ruins have polished columns and are supported by broad beam. Some scholars have frowned upon the practice. Many tourists think it is great. At the entrance there is a bust of Sir Arthur John Evans, the discovered of the site, who spent 25 years excavating and reconstructing it.

Evans and others involved in reconstructing Knossos took quite a few liberties. Buildings that are more than 1000 years older than the Parthenon look newer and in better shape. The colors definitely makes the ruins more dramatic but in the end also make them look artificial, the same way colonizing a classic film does. The garishly painted frescos which look more like the work of art-nouveau school, than the Minoans are down right insulting. Still, I guess, they are kind of fun and I guess people visit ruins for entertainment.

Minoan Palace at Knossos

Knossos occupied a valley next to the coast and was home to perhaps 80,000 people. It survived for seventy years after the Thera eruption that is thought to have had a hand in the demise of Minoan culture. Knossos was probably located were it was because it near the coast and near the fertile plains of Messera which are on the other side of some mountains.

Knossos is a labyrinth of storerooms, workshops, and ceremonial halls. Minoan columns were tapered only at the top and looked the handles of gavels.The Minoans built there palaces from poros (a kind of soft sandstone, sandstone and gypsum). Geologists worry that if current erosion rates continue Knossos will weather away to nothing in a few hundred years.

King Minos's Palace

King Minos's Palace is the largest structure at Knossos. A vast complex that encloses a courtyard and occupies a large part of Knossos, it covers over 21,000 square meters (about five acres) and embraces the remains of the throne room, the royal suites, Pillar Hall, the Central Court, Grand Staircase, Hall of Double Axes, a treasury, an arsenal and a theater.

The Palace of Minos is so vast and complex--- it is several times bigger than Malia, 20 miles to the east, the next largest Minoan palace---it is no surprise that it has been linked with King Minos and the legend of the Minotaur and the labyrinth even though there is no proof or even hints that are related to one another.

Dolphin room at Knossos

Visitors entering King Minos's Palace from the west walk along a hallway called the Corridor of the Procession Fresco which is paved with gypsum flagstone and decorated with a frescoe showing visitors bearing gifts. This passages lead to 164-by-82-foot courtyard., where public gatherings and ceremonies took place. Around the courtyard are residents of the Knossos aristocracy, reception rooms, treasuries, storehouses, administrative archives and potter's and smith's workshops.

In the throne room is a stone-lined tank called Ariadne's Bath. Archeologist believe that the tank was basin used in rituals. The stone chair on a platform, described as a throne, is thought to have been designed for a woman. Nearby are storerooms that held grain, olive oil and wine. Paintings along the wall of the palace at one time contained hundreds of figures---musician, butterflies, sphinxes, bull leapers and griffins.

The huge central court is where sacrifices, bull leaping contests, and religious ceremonies were held. Unexplained holes in the court may have been used to erect barricade to protect the audience from the bulls.

Minoan PalaceIn the west wing there are three religious shrines, each made up of small room with columns topped by bull horns. Up a flight a stairs is sanctuary hall with religious paintings where communion feasts were possibly held. Beneath these halls are warehouses with 400 giant jars that could each hold 65 gallons olive oil or wine. In one of the 150 palace room is what is believed to be the oldest serving throne in the world, a gypsum chair with griffin's painted on it.

The western court features raised walkways, a small porch and gypsum wall still black from the fire that destroyed Knossos. Near the palace a stone causeway leads to a wide-stepped portico. Outside the palace are the foundations of homes of ordinary people and cemeteries. On the east side of the palace is an area believed to be a residential neighborhood inhabited by advisors to the rulers. There is restored staircase built around a well that leads to apartments decorated with frescoes of dolphins.

The Grand Staircase and the much of the Domestic Quarter are well preserved because they had been built into the side of a hill. Here Evans found "gypsums, paving slabs, door jambs, limestone bases, the steps of the stairs, and other remains." Other Minoan ruins near Iraklion include Arkanes and Anemomospilia.

Phaistos and Arkhanes

Snake GoddessArkhanes (a few miles south of Knossos) lies at the end of a path with a pleasant view of a gorge. An early Minoan group graveyard has been found here. In the 1960s over 200 human skulls were excavated here along with a temple of the dead built in 1800 B.C. In one tomb a woman was buried with a horse and a bull head. The woman was buried in a clay bath, wearing 140 pieces of gold jewelry.

Phaistos (two hours south of Iraklion) was the second most important Minoan city after Knossos. The layout of the city city is similar to that of Knossos. Purists like these ruins better because they have been left more or less untouched, with the various layers showing the different periods of development.

Phaistos lies on the southern side of Crete with views of snow-capped Mt, ida and the sea. About half of the palace, said to be the second largest in Minoa, has collapse down the hillside. What is left is entered through a wide stairway. Only walls and foundations are left. Near Phaestos is another Minoan site, Hagia Triada.

Mallia (20 miles east of Knossos) it is said contains the next largest Minoan palace after Knossos. Only walls and foundations are left. The site has a roof over it. There are large silos grain and the palace has pillar crypt and views of the sea. Gournia is a Minoan sight with earthen courtyards, walls, streets and steps that include 70 homes, metalworkers shops, a factory for pressing olive oil and wine and a palace and cover an area over 18,000 square yards. Unearthed here were ancient awls, nails, razors, tweezers, knives and carpentry tools.

Minoan Language

Tablet with Minoan writingMinoans were the first Europeans to use writing. Their written language was only deciphered in the late 1990s. Known as Linear A, it contains 45 "letters" and is categorized as an ancient form of Greek. The few scraps of Minoan text that have been translated are mainly records of trade, inventories of military equipment, and lists of harvests of wheat and olives. Linear A clay tablets, dated between 1900 and 1700 B.C., were found at Knossos. They were found along with tablets with Minoan hieroglyphics, Linear B, and a still undeciphered Cretan script dated to 2000-1700 B.C.

The Phaistos Disk, found in the ruins of the 3700-year-old B.C. palace of Phaistis, is the earliest know example of printing. The six-inch, baked-clay disk contains 241 pictorial designs comprised of 45 different letters arranged in a spiral formation. The symbols were placed on the disk with a set of punches, one for each symbol, using the same concept as movable type.

Minoan Religion

The Minoans had no temples and no large cult statues from what we can tell. Worship centered around sacred caves and groves where it is believed the Minoans believed to be their deities dwelled. Minoan religious objects consisted primarily of small terra-cotta statuettes.

The Minoans worshiped what has been described as a mother goddess, or snake goddess. This goddess was associated with animals, particularly birds and snakes, the pillar and the tree, and sword and the double ax. She was often depicted with snakes around her arms and lions at her feet. Her companion Zeus, the Monoans believed, was born on Mt. Ida on Crete. A popular image of the mother goddess shows her as a bare breasted snake goddess with snakes crawling up her arms, circling her head and tied into a knot about her waist. One of the unusual things about the worship of snakes by the Minoans is that Crete has virtually no snakes.

Most of the sculpture of earth goddesses found before in 2000 B.C. in mainland Europe were plump big-breasted women with folds of fat and little lines representing their genitalia. On Asia Minor and the Cycladic islands off of Greece little girlish figures with small beasts triangles for genitalia were common between 2500-1100 B.C.

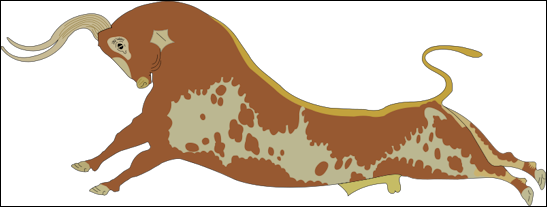

The Minoans also worshiped male deities as reflected in the large number of male figures found and the quality of their craftsmanship. Egyptian symbols and deities, such as Orisis and Anubis, pop up frequently in Minoan religious iconography. Butterflies symbolized long life to the Minoans and bulls represented strength and fertility.

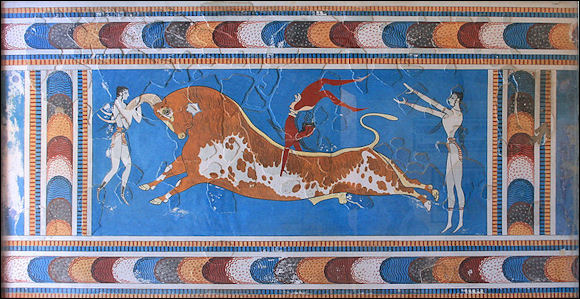

Minoans, Bulls and Bull Leaping

Bulls held a high place in Minoan culture. They appeared again and again in paintings and sculpture. Some have suggested that the Minoans worshiped bulls and that this may have grown from the cult surrounding the Egyptian god Hathor, who was often pictured as a divine cow.

Some scholars have said that the Minoans conducted sacrifices of bulls whose horns were covered with gold. Evans said that large double-headed axes found at Minoan sites were likely used to ritually kill bulls, arguing that they were too big to do anything else. Now it appears that the double headed ax was more likely a symbol of the equinox.

Some have suggested that bull leaping was a popular Minoan sport. Frescoes appear to depict male and female athletes doing flips over bulls charging at them at full speed. Some the “players” appear to grab the horns and hold on to the bull's back as they leap over.

Scholars have interviewed rodeo experts to get their view on the depictions of of “bull leaping." Some concluded that picture were not of bull leaping: the sport would simply be too dangerous, they say, as bulls usually turn their heads when confronted and anyone who tried to leap through their horns would likely be gored. Some scholars say that the “bull leaping” images represent something else, perhaps the constellations Taurus and Orion.

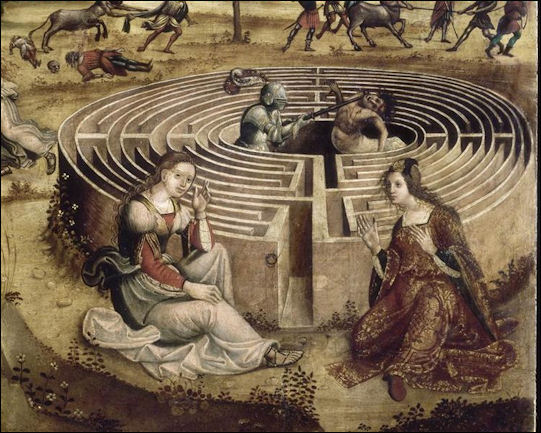

Minotaur, Theseus and the Labyrinth

The story of the Minotaur and the labyrinth, according to to some, is set in Crete, presumably during the Minoan era. According to legend, King Minos was a wise leader and a just lawgiver who ruled Crete from Knossos and lived in a magnificent palace. One day the sea-god Poseidon gave him a magnificent white bull that was intended to be sacrificed in the sea god's honor. Minos greedily kept the bull instead and Poseidon got even with the king by casting a spell on his wife, which made her want to make love with the bull, which she did, producing the Minotaur. Daedalus, the Athenian architect who later tried to fly to Sicily with wings made of wax, built the Labyrinth to imprison the Minotaur.

After King Minos's son was killed in Athens the king captured Athens and secured an annual tribute of seven youths and seven virgins to be eaten by the Minotaur. One of youths offered to the Minotaur---Theseus---fell in love with King Minos's daughter. Daedalus gave Theses a ball of string so that he could find his way out of the labyrinth of he managed to kill the Minotaur. After slaying the Minotaur Theseus fled Crete with king's daughter but as was true with heros in other Greek myths, such as Jason from the Argonauts, Theseus abandoned the girl after winning his freedom.

medieval rendering of the Minotaur myth

The Minoans believed that King Minos was the son of Europa, the daughter of King Sidon, and Zeus transformed into a bull. The association of the Minotaur myth with Knossos can be traced to Sir Arthur Evans, the British adventurer, who excavated Knossos in the 1890s. He reportedly was struck by the size of Knossos and its large number of rooms that he figured it must be the source of the labyrinth myth. Some have said he defied one of the cornerstones of archaeology by forcing evidence to fit his model rather than letting evidence speak for itself. Evans is also the source of some other dubious claims about Minoa.

Minoan Life, Bathtubs and Clothes

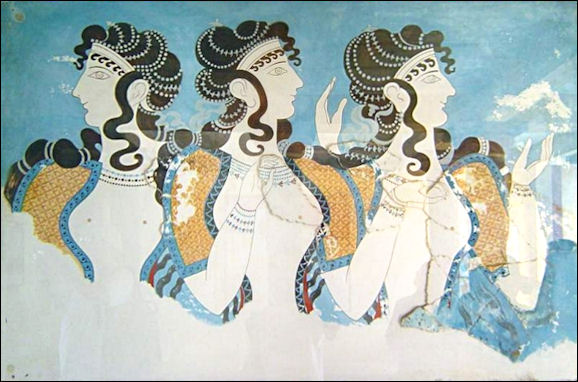

One gets a sense that the Minoans enjoyed life. Minoan artwork and sculpture often depicts bare breasted women, dancing figures, men playing sports, and people partying and shaking Egyptian rattles and singing so hard their ribs are pressed against their skin from lack of breath. Minoan art contrast markedly with early Mesopotamian and Egyptian art which was often rigid and formal.

The Minoans stored olive and grain in huge clay jars and drank wine. They harvested grain with sickles and knocked olives off of trees with sticks much as modern Cretens do today Childhood skull shaping has also been practiced by Minoans as well as by Egyptians, ancient Britons, Mayas and New Guinea tribes.

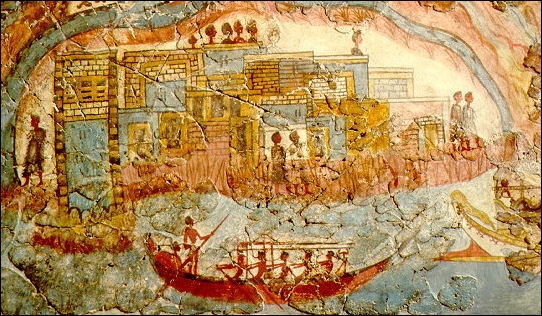

Akrotiri fresco of a Minoan town

The oldest known confirmed bath tub come from Minoa. Shaped somewhat like a modern tub, it was found in the palace of King Minos in Knossos and has been date to around 1700 B.C. Minoan nobility took baths in stone bathtubs "filled and emptied with vertical pipes cemented at their joints." Late these were replaced with glazed pottery pipes which were slotted together like modern ones and carried hot and cold water. The royal palace at Knossos also featured a latrine with an overhead water-holder that has been described as the world's first flush toilet.

Based on images in frescoes and sculptures, Minoans wore leopard skin loin clothes and colorful hippie-like outfits. Some statues show a women, or goddesses, wearing what looks like a 19th-century-style dress with an open area at the top for exposed breasts supported on a bodice. Minoan loin-clothes were similar to those worn by the Egyptians.

Bernice Jones, a professor at Queens College in New York, reconstructed several Minoan garments, including the breast-revealing outfit of the snake goddess, a tube dress and a sheer top found in the depiction of a woman in a fresco in Thera's House of Ladies, and a breast-revealing blouse worn by a dancer depicted in a fresco in Hagia Triada.

Minoan Art

Minoan frescoesThe Minoans are widely admired today for their art. They produced lovely frescos of dancers and bulls and made wild abstracts patterns on vases. Some Minoan engravings of women give them strange robot-like heads. They also produced extraordinary rhytons (liquid-containing vessels) made to look like bulls heads.

Animals and sea creatures were commonly depicted in Minoan art. Octopuses strangled vases, dolphins leaped from murals, and mountain goats dashed across vessels. One mural fragment shows a cat stalking a pheasant from behind a bush. One scholar claimed that the Minoans had a "passion for rhythmic, undulating movement."

The Minoans created pottery on hand-tuned wheels (2500 B.C.) and made earthen storage jars as tall as a man and thin shelled libation vessels decorated with starfish and sea shell motifs. Potters in Crete still make pottery using the same techniques as the Minoans.

See Minoan Religion

Phaistos Disk and the Collection at the Heraklion Museum

Phaistos diskHeraklion Museum is one of the best museums in Greece and contains almost all of the world's Minoan artifacts. Among the museum's treasures are ceramic polychrome vases found in the Kamares caves; marble vases encrusted with precious and semi-precious stones; sealstones carved out of semiprecious stones; gold ornaments; frescoes and sarcophagi.

Particularly interesting are ceremonial axes and knives used in sacrifices; and libation jars used to collect the blood from the animals necks. Goats and bulls were the animals most commonly offered. Paintings on sarcophagi suggest that spotted bulls were the animals of choice. These same paintings show that the bull was tied down to a table and serenaded by a flutist while it bled.

Human sacrifice although rare were sometimes performed. Skeletons and artifact from the archeological site of Anemospilia seem to show a human sacrifice that was interrupted in mid-course by an earthquake which not only finished off the sacrifice victim but also spelled doom for the sacrificers as well.

Vases depict men partying, shacking Egyptian rattles and singing so hard the ribs are pressed against their skin from lack of breath. A popular image was the bare breasted snake goddess with snakes crawling up her arms, around her head and tied into a knot about her waist. One of the unusual things about the worship of snakes by the Minoans is that Crete has virtually no snakes.

The museum also contains the 3,600-year-old Phaistos Disk, the earliest know example of printing. Found in Phaistos Crete, the disk features 241 pictorial design imprinted with seals and arranged in a spiral. Some miniature plaques show what Minoan houses looked like. There are also sculptures of dancers and bare-breasted maidens with snakes in their hands, vessels with starfish; massive knuckle covering gold rings with women with robot heads and frescoes of bull leapers.

Minoan Homes and Architecture

The Minoans built multi-storied palaces with as many as 1,500 rooms. Most of the large Minoan structures had balconies and were set up around courtyards. Most also had windows, sitting rooms with adjustable partitions, indoor pools, and verandas with wonderful views. Some had advanced indoor plumbing and drainage systems. Many Minoan cities and buildings lacked fortification which has led archaeologists to believe they were a relatively peaceful civilization.

The Palace of Minos was so vast and complex it was no surprise it gave birth the legend of the labyrinth. It covered nearly five acres and was several times bigger than Malia, 20 miles to the east, the next largest Minoan palace. Buildings in Minoan cities such as Knossos possessed latrines, skylights, ventilation, and water conduits for drainage.

The Minoans built their palaces from poros (a kind of soft sandstone), sandstone and gypsum. Columns were made of wood. None survive today. The oldest Minoan buildings were built of fired mud bricks, a construction material that was later abandoned.

Minoan Trade

The Minoans were the first great maritime culture. They used sailing ships with oars and are believed to have invented the keel. They stored foodstuffs in massive jars called pithons .

The Minoans traded all over the Mediterranean. To make bronze the Minoans traded with Cyprus for copper and with Assyrian traders for tin from Anatolia and the Hindu Kush mountains.

The Minoans grew rich from trade with Egypt and the East Mediterranean. Based on the fact that Minoan ports had elaborate harbors and Minoan goods have been found in Egypt and elsewhere it was believed they were primarily traders.

No Minoan shipwreck has ever been found. Archaeologists would love to get their hands on one.

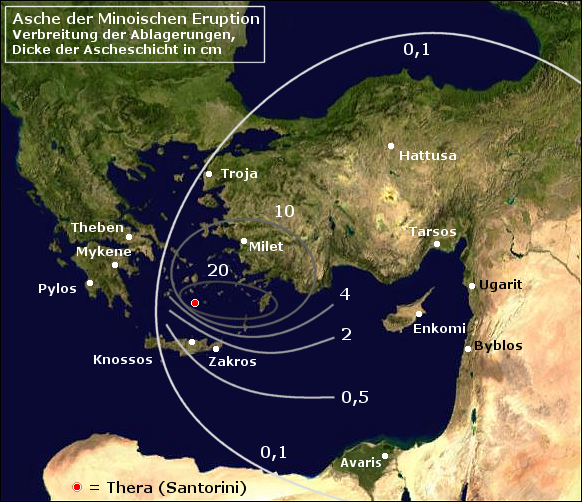

Ash from the Thera eruption

Thera Volcanic Eruption

In 1645 B.C., a volcano on Santorini erupted with such force that some believe it caused the collapse of the Minoan civilization on the island of Crete, 70 miles away. Thirteen cubic miles of material exploded into the sky. Settlements on Santorini were buried under a thick layer of ash thicker than the one that covered Pompeii. [Source: William Broad, New York Times, October 21, 2003]

The main eruption was preceded by a smaller one---a shower of light pumice that buried the town of Akrortiri, down slope, under many feet of ash. This may have sent most of the residents away. No skeletons or human remains have been found on Santorini .

The main eruption began when sea water entered a vent of the volcano and mixed with magma and gases, producing an ultra-violent explosion. The center of Thera collapsed into a sea-filled caldera. Santorini was buried Pompeii-style under ash, up to 900 feet deep, that preserved frescoes and wall paintings that recorded everyday life from the period and contained Egyptian motifs.

The explosion produced a huge tsunami, possibly 300 feet high. This tsunami swamped and hit the coast of North Africa, sending water 200 miles up the Nile. On Crete, an 50-foot-high tsunami wiped out coastal settlements. Inland ash may have ruined crops and grass that fed livestock.

The Thera eruption may have been the largest eruption on Earth in the last 10,000 years. Some scientists have calculated was 90 times greater than the one at Mount St. Helens and four times greater than Krakatau, which killed 36,000 people . Some say it was much larger than that, perhaps even larger than Tambora, which erupted in 1816 and produced the year without summer and famines in the United States.

fresco of women

Thera Volcano and the End of Minoa

After the Thera eruption 50 foot tsunamis smashed against Crete's shores, smashing ports and fleets and severely damaging in the maritime economy, which was vital for the Minoans as it was an island civilization. Ash levels of 10 feet were recorded 20 miles away on the island Anafi. That was incredible amount of ash that distance away.

In 1939 Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos theorized that eruption of Thera caused the collapse of Minoan civilization with damaging earthquakes and tsunamis. Some doubts were raised about earthquake side of the story because earthquakes associated with volcanic eruptions are usually not that strong. In the mid 1960s scientists dredging up sediments found thick layers of ash linked to Thera's eruption and found it covered thousands of square miles.

But the theory was given a blow in 1987 when the date of the eruption was set at 1645 B.C. based in the presence of frozen ash in Greenland ice cores, 150 year before the pervious dates, and 200 years before the steep decline of Minoan culture. The theory was given another blow in 1989 when a Minoan house was found built above the ash layer.

Minoan auroch

Now the reasoning goes the eruption took time to bring down Minoa. Some archaeologists say the eruption and tidal waves did not destroy Minoa rather it weakened, making it vulnerable to conquest. An the Mycenaeans were the ones who conquered it. They theorize the that ash from the eruption could have destroyed crops, brought about a famine, opening the way for a conquest from the Mycenaeans.

A century earlier a large earthquake destroyed the palace of Knossos. It was rebuilt. An earthquake that occurred around the time of the Thera explosion damaged the palace. In the decades that followed all the major palaces of Crete were damaged by fire, most likely by invaders.

By 1450 B.C. nearly all Minoan palace-cities, except Knossos were mysteriously destroyed. Around this time pottery styles and writing styles changed reflecting styles introduced from Mycenae, suggesting that the Mycenaeans took over Crete. By the 14th century B.C., Knossos appeared to be under the administration of the Mycenaeans.

Impact of Thera Eruption on the Eastern Mediterranean

The Thera eruption had a dramatic affect on the eastern Mediterranean that lasted for decades, even centuries. Dense clouds of volcanic ash and deadly tsunamis were generated over a huge area, crippling ancient cities and fleets, setting off climate changes, and sowing political unrest.

The Thera eruption had a dramatic affect on the eastern Mediterranean that lasted for decades, even centuries. Dense clouds of volcanic ash and deadly tsunamis were generated over a huge area, crippling ancient cities and fleets, setting off climate changes, and sowing political unrest.

The Thera eruption produced two large ash clouds. One that was blown by lower atmosphere winds to the southeast towards Crete and Egypt and another that was blown by the jet stream in the stratosphere to the northeast over Anatolia (Turkey). Dr. Peter Kuniholm, a tree ring expert at Cornell, found that trees found in an Anatolian burial mound grew three times faster that normal for about half a decade around the time of eruption, presumably because the ash turned the region's normally hot, dry summers into ones that were unusually cool and wet.

But although the ash seems to have helped trees it is thought it severely damaged wheat fields and reduced harvests. Many think it was the primary factor behind Mursilis, king of the Hittites, setting out from his Anatolian kingdom and attacking Syria and Babylon, which lay between the two plumes, and seizing their stored grains and cereals. This in turn prodded Babylon towards collapse and hurt one of its allies, the Hyksos, who ruled Egypt and traded with the Minoans.

The plagues described in the Bible are thought by some to be a result of the Thera volcano. The explosion and land submerged by the tsunami may be the source of Plato's story of Atlantis. Some scholars speculate that ancient Minoa or Thera may were have been Atlantis, which Plato, supposedly heard about from Socrates who in turn heard about it from Egyptians. Some historians believe the Thera eruption changed the entire coarse of history. With Minoans out of the picture, they hypothesize, cultures on the Balkan peninsula were able to develop into classical Greece.

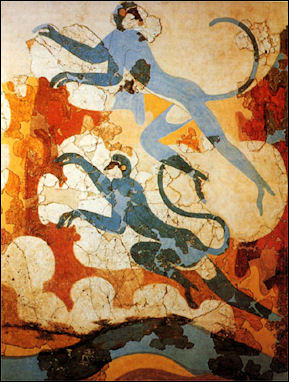

Outside of Fira on Santorini itself are the ruins of Akrotiri, a Minoan settlement, that was buried Pompeii- like by the Thera eruption. The leader of the excavation died in 1974 when he fell in one of the excavations and hit his head. Few artifacts have been found which means the people fled before the volcano erupted. Only a small area has been excavated from the hardened volcanic ash, revealing houses with that are now in the Athens Archeological Museum.

Discovery of Minoa

Akrotiri blue monkeysThe Palace of Knossos and Minoan culture were discovered in 1900 by Sir Arthur Evans, an Englishman who had come to Crete to search for information about the origins of Mycenaean culture.

Evans traveled to Crete several ties between 1894 and 1899. He began his search at the mound of Kephala, outside Heraklion, where seals with Mycenaean-like marking were found. Twenty-five years he finished excavating the 5½ acre Knossos Palace.

Evans used his own personal fortune, worth several million dollars in today's money, to finance the dig. Based on the presence of numerous images of bulls and the maze -like quality of the palace, he decided that Knossos was the source of the Minotaur myth and labyrinth story. He also found written scripts which he labeled Linear A and Linear B.

Evans work as an archeologist was shoddy to say the least. He replaced missing columns and support beams with reinforced concrete. Archaeologists that followed found concrete covering up the original gypsum and sandstone. In the original excavations and Evan did not indicate different time periods.

Other important Minoan sites include the Gorge of the Dead, an unplundered palace found in 1962 by Nicoloaos Platon in Zakros; a Bronze Age settlement on Santorini preserved like Pompeii found on Spyridon Marinatos; burial chambers of a queen or priestess found in Arkhanes; the grand stair case of Phaistos, the central court at Mallia, and the throne room of Knossos.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Most of the information about Greco-Roman science, geography, medicine, time, sculpture and drama was taken from "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. Most of the information about Greek everyday life was taken from a book entitled "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum [||].

No comments:

Post a Comment