Crassus (Marcus Licinius Crassus: 115-53 B.C.). A noble and very rich Roman, a follower of Sulla who became famous in 71 B.C. with the cruel repression of Spartacus’s slave revolt.

In 60 B.C. he became part of the first triumvirate with Caesar and Pompeius and was appointed consul in 55 B.C. While proconsul in Syria, he organized a military expedition against the Parthians. This ended with a disastrous defeat in Carrhae (today known as Harran, Turkey) in which the ensigns of the legions were lost and where he himself lost his life.

Caesar (Gaius Julius Caesar: 100-44 B.C.). A representative of the popular faction and member of the Julia family (which allegedly descended from Aeneas), he led a brilliant political career and formed the first triumvirate with Crassus and Pompey in 60 B.C.

He became consul in 59 B.C. and conquered Gaul and up as far as Britannia. The Senate and Pompey deprived him of his military power. In 49 B.C. he crossed the Rubicon River (at that time the frontier of Italy) with his legions and waged a bloody civil war against Pompeius. His victory made him the undisputed leader of Rome: he was consul for 5 years (48 B.C.) and dictator for 10 (46 B.C.).

Thanks to his authority and to the riches acquired, he began a series of legislative reforms and built many important monuments (Caesar’s Forum, Basilica Julia, Curia, Saepta Julia).

Much of his work was interrupted by a fatal conspiracy hesxded by Brutus and Cassius. Upon his death he was nominated god and venerated in a temple built in the Roman Forumon the site of his cremation.

Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius: 82-30 BC). Caesar’s grandson and lieutenant. He was the principal figure involved in the vendetta against Caesar’s assassins, Brutus and Cassius.

In 43 BC he constituted the second triumvirate with Lepidus and Octavian, which led to the division of the Roman territories, the Eastern regions being assigned to Mark Antony.

He fell in love with Cleopatra and married her giving her many Roman possessions and entering into open conflict with the Senate and Octavian. The civil war ended with the naval battle held in Actium in 31 BC: Mark Antony committed suicide in Alexandria in 30 BC.

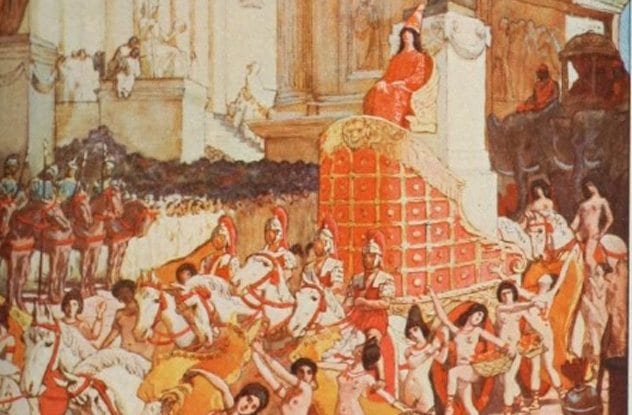

Cleopatra (69-30 BC). Daughter of the king of Egypt, Tolomeus Auletes. Upon her father’s death, she was dispossessed by her husband and brother, Tolomeus Dionysius. I

n 46 BC she was once again placed on the throne thanks to Julius Caesar, from whom she had a son, Cesarean. Upon the dictator’s death she married Mark Antony, with the ambitious project of creating a powerful reign throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and fought directly with Octavian.

Following the defeat in Actium (31 BC) she committed suicide by allowing herself to be bit by a venomous serpent.

Agrippa (Marcus Vispanius Agrippa: 63-12 BC). A follower of Octavian, he led the principle civil war battles with great determination, among which the final clash in Actium against Mark Antony and Cleopatra (31 BC). He was Augustus’s right arm and son in law and was actively involved in the reorganization of the Empire.

Through the construction of many important monuments (aqueducts, Baths of Agrippa, Pantheon, etc.) he contributed to the erection of the new Imperial Rome.

Augustus (Caius lulius Caesar Octavianus Augustus: 63 BC-14 AD): Octavian, who was born in a plebeian family, was designated by his uncle Julius Caesar as son and heir. Therefore, he changed his name to Caius lulius Caesar Octavianus.

Upon the dictator’s death, together with Mark Antony and Aemilius Lepidus, he formed the second triumvirate, but following the final defeat of the Cesareans in Philippi (42 BC), the possibility of dividing the Roman territories into three parts vanished quickly.

Civil war broke out and Octavian and Mark Antony, who was already married to Cleopatra, became enemies. The victory at Actium in 31 BC allowed the young Caesar to conquer the absolute domain over Rome. This became official in 27 BC when the Senate conferred him the title of Augustus (inherited later also by all future Roman Emperors).

Holding all powers, he radically reorganized the Roman state with a series of legislative, administrative and social reforms thus initiating a lengthy period of peace identified as the new golden age.

During his rule, Rome, together with all the other cities of the empire, was involved in vast construction programs ranging from the restoration of the more ancient monuments to the building of new architectural complexes. In his will, Augustus could proudly claim to have found a city built of bricks and to have left behind him one built of marble.

Tiberius (Tiberius Claudius Nero: 42 EC-37 AD). The second Roman emperor, son of Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla (Augustus’s second wife). He was an able military leader, but Augustus appointed him as his successor only following the premature death of the emperor’s closest blood relatives. His rule was filled with conspiracies and suspicion to the point that the emperor retired to his villa in Capri in 27 AD.

Caligula (Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus: 12-41 AD). The son of Agrippina (Augustus’s niece) and of Germanicus.

He was nicknamed Caligula (from the term “caliga” meaning military shoe) since his childhood was spent in legionary camps. In 37 AD he became emperor and his rule was marked by absolutism and by dissolute behavior until he was killed in a conspiracy.

Claudius (Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus: 10 BC-54 AD). Acclaimed emperor by the Praetorians upon Caligula’s death (41 AD), the elderly Claudius succeeded in restoring order despite the pressure of his wives, Messalina and Agrippina.

During his rule, Britannia was conquered and Mauritania, Thracia and Licia were added to the empire. Many public works were accomplished, most of which of public interst (the port of Claudius near Ostia, the Claudian aqueducts in Rome, etc.).

Nero (Nero Claudius Drus us Germanicus Caesar: 37-68 AD). The son of Agrippina Minor who was adopted by Claudius and became emperor in 54 AD Following an initial period of peaceful leadership, the young emperor changed political line and accentuated his tyrannical tendencies aimed towards an absolutist monarchy.

His name is linked with extravagance, but above all with the serious fire in 64 AD which destroyed most of Rome and to his attempt to blame the Christians for the fire.

His eccentric behavior and political line were directly reflected in the accomplishment of significant architectural programs such as the Domus Transitoria and the Domus Aurea, the lavish and grandiose palaces that Nero had built as his residences.

Following a series of conspiracies Nero committed suicide during a revolt headed by his own governors in 68 AD, thus marking the end of the first Roman imperial dynasty, the Julius Claudii.

Vespasian (Titus Flavins Vespasianus: 9-97 AD). Born in Sabina, Vespasian was supported by the legions appointed in the Orient and defeated Vitellius thus marking an end to a year of civil wars and becoming the first emperor of the Flavian dynasty.

Vespasian’s political line was aimed at replenishing the state treasury by favouring the middle classes and eliminating Nero’s absolutist trend.

The gradual elimination of the buildings of the Domus Aurea which was replaced by public monuments proved particularly significant. Some of these monuments included the Colosseum (whose building was begun by Vespasian) and the Temple of Peace, the fourth imperial forum.

Titus (Titus Flavius Vespasianus: 39-81 AD). Successor to his father Vespasian in 79 AD, Titus reigned for only two years during which took place the eruption of the Vesuvius which buried Pompeii and neighboring cities (79 AD) and a huge fire which destroyed many parts of Rome (80 AD).

Despite his short-lived rule which was marked by the continuation of the public building program begun by his father, his meekness and benevolence led him to be nicknamed the “delight of the human race”.

Domitian (Titus Flavius Domitianus: 51-96 AD). Following the premature death of Titus in 81 AD, his brother Domitian was made emperor, the last of the Flavian dynasty.

During his rule he energetically defended the empire’s northern borders and improved internal administrative organization, also completing construction programs begun by his father (among which the Colosseum) and building new important architectural complexes such as the imperial palace on the Palatine hill. Despite these positive aspects, repeated contrast with the senatorial aristocracy and his tendency towards an absolutist monarchy led to a period of terror which was ended by a conspiracy.

Trajan (Marcus Ulpius Traianus: 53-117 AD). Following Domitian’s death, Nerva was nominated emperor (96-98 AD) who chose Trajan as his successor, a military leader of established experience loved both by the army and the Senate.

Born in Spain, Trajan was one of the greatest Roman emperors. During his rule (97-117 AD) the empire reached its maximum expansion with the conquest of Dacia (present Romania) and of vast Eastern territories (Arabia, Mesopotamia, Armenia, Assyria).

The acquisition of new riches allowed Trajan to lead a social policy in favor of the poor and to accomplish a grandiose program of public works in Rome and in the provinces.

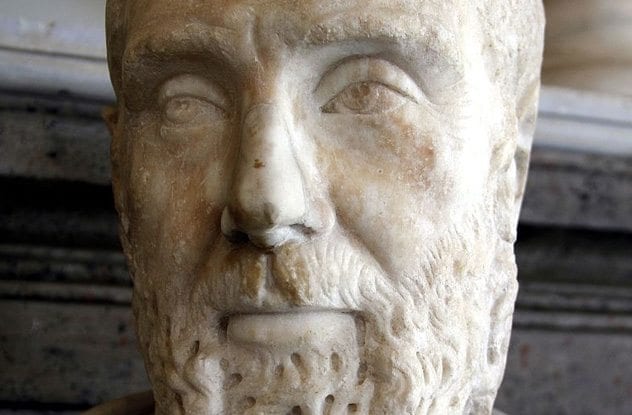

Hadrian (Publius Aelius Hadrianus: 76-138 AD). Hadrian became emperor in 117 AD. He was adopted by Trajan and was also Spanish.

The new emperor’s political orientation soon revealed to be completely different from the orientation of his predecessor. Aware of the difficulties that were to arise in defending such a vast territory, Hadrian abandoned the territories east of the Euphrates and gave special attention to the borders of the empire accomplishing, among other things, the Vallum in Britannia.

Hadrian stood out for his cultured nature and artistic sensibility; he too was an architect and painter. During his rule which was principally peaceful, with the exception of the violent Judaic revolt, Hadrian traveled extensively throughout the provinces of the empire preferring to reside in his beautiful villa near Tivoli rather than in Rome.

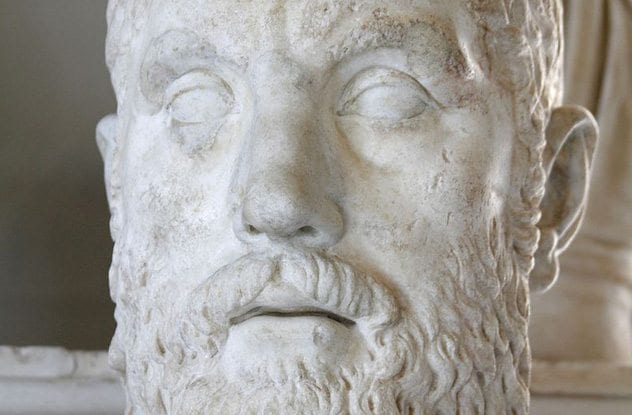

Antoninus Pius (Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius: 86-161 AD). Chosen by Hadrian as his heir, Antoninus became emperor in 138 AD, the first of the Antonine dynasty. His lengthy rule was a time of peace and prosperity troubled only by sporadic unrest in the provinces. Upon his death in 161 AD, he was succeeded (as established by Hadrian) by

Marcus Aurelius (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus: 121-180 AD) who ruled together with his adopted brother Lucius Verus who died in 169 AD.

In spite of his peaceful nature and his stoic character, Marcus Aurelius had to face lengthy wars in the Orient against the Parthians and sustain pressure by the Quads and the Marcomanns along the northern borders. Such battles are depicted on the Antonine Column. In addition to these difficulties, his rule was marked by a series of plagues and a difficult economic crisis which marked the beginning of the fall of the empire, accentuated by the poor rule of his son and heir, Commodus (Lucius Aurelius Commodus), emperor from 180 to 192 AD.

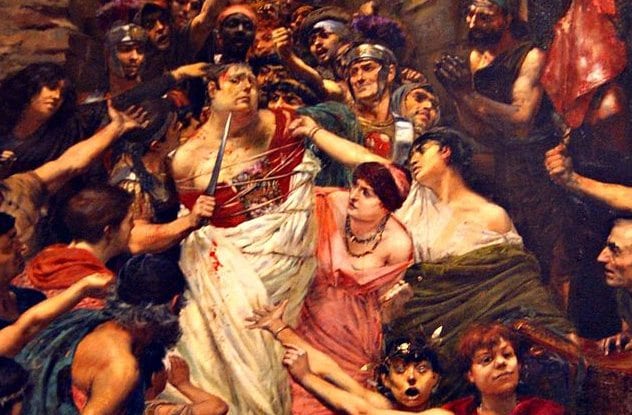

The bloody civil wars that broke out upon Commodus’ death ended with the victory of Septimius Severus (Lucius Septimius Severus: 144-211 AD), emperor in 193 AD, and the first of the Severian dynasty. Born in Leptis Magna in Tripolitania ( present day Libya) to a family of Italic origins, Septimius Severus reorganized the Roman empire and its defenses and guided a victorious expedition in the Orient which allowed the annexing of Mesopotamia. During his rule, also thanks to the marriage with Julia Domna (a noble Syrian), religion was influenced by oriental elements.

Upon Septimius Severus’s death in 211 AD, Caracalla (Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus: 186-217 AD), his first born son became emperor. Shortly after, he killed his brother Geta with whom he was to have shared the empire. During his rule, Caracalla promulgated the Constitutio Antoniniana which rendered the provincials equal to Roman citizens. During an expedition against the Parthians Caracalla was killed by one of his own soldiers.

Diocletian (Caius Aurelianus Valerius Diocletianus: 240-316 AD). Acclaimed emperor in 284 AD, Diocletian marked the end to a lengthy period of uncertainty and serious economic and military crisis.

In 286 AD he joined power with Maximianus, dividing the empire into two parts governed respectively by an emperor (named Augustus) and his deputy (defined as Caesar). This established a tetrarchy with the obvious intention of guaranteeing the succession to the throne.

In order to reorganize the state, the empire was divided into new territorial zones and the administration experienced fiscal and economic reforms. When Diocletian abdicated in 305 AD, withdrawing to his palace in Split, the tetrarchy was dissolved as a result of contrasts and personal ambitions of his successors thus leading to a new period of civil wars.

Appius Claudius Caecus. A Roman politician (IV-III BC), censor and consul, writer and orator, he owed his blindness (according to ancient sources) to the punishment of the gods inflicted on him for his religious reforms. He appointed the building of the aqueduct and street that are both named after him. He promoted electoral reforms in favor of the lower classes.

Apollodorus of Damascus. Trajan’s official architect (both civil and military) who accompanied him in the Dacian wars where he built an impressive bridge over the Danube depicted in Trajan’s Column. He also planned and designed the large Forum for the emperor which was to be the last of the imperial forums. The irreparable conflict with the emperor’s successor, Hadrian, caused the architect’s death.

Constantine. Son of the tetrarch Costantius Chlorus and Helena, he was emperor from 306 to 377 AD. He was acclaimed emperor by the troops in Britannia and this radically changed the mechanism of succession devised by Diocletian with the Tetrarchy. Those were years of wars and battles, particularly with Maxentius and Licinius.

In 313 he legalized Christianity and in 330 he moved the capital to Byzantium, renamed Constantinople.

A great emperor that maintained a difficult balance between late paganism and growing Christianity.